As an art form the miniseries is arguably well past its prime, at least in the United States (it's alive and well in Britain, as shown by innumerable BBC costume dramas). The gold standard for the American miniseries, to my mind at least, is North and South (1985), which despite thick layers of cheese had star power and soapy drama enough to satisfy. Last year's Hatfields & McCoys aims for similar territory, but it's hamstrung by its own incuriosity and excessive reverence.

During the American Civil War 'Devil' Anse Hatfield (Kevin Costner) and Randall McCoy (Bill Paxton) fight for the Confederacy together, but a rift develops between the men when Hatfield, recognising the futility of the fight, deserts and returns to West Virginia. He increases his wealth by buying up and logging woodland, while McCoy returns to Kentucky a broken man after years in captivity. His resentment increases when Harmon McCoy (Chad Hugghins) is found murdered, with 'Devil' Anse's uncle Jim Vance (Tom Berenger) the prime suspect.

The hostility between the families worsens when Johnse Hatfield (Matt Barr) falls in love with Roseanna McCoy (Lindsay Pulsipher). Roseanna is thrown out by Randall, and 'Devil' Anse reluctantly allows her to stay with the Hatfields but will not allow Johnse to marry her. Johnse chooses loyalty to his family over the pregnant Roseanna, who is sent away to live with an elderly relative. Shortly after, three of McCoy's sons murder Ellison Hatfield (Damian O'Hare), and are in turn captured and executed by the Hatfields. The bloodiest phase of the feud begins when McCoy and his lawyer kinsman Perry Cline (Ronan Vibert) hire ex-Pinkerton bounty hunter 'Bad' Frank Phillips (Andrew Howard) to lead a posse into West Virginia and hunt down the Hatfields, who have withdrawn into the mountains.

Hatfields & McCoys boasts glorious production design: the costumes alone are worth the price of admission. It's generally well directed by Costner's longstanding collaborator Kevin Reynolds, with the noticeable exception of the fairly embarrassing Battle of Grapevine in the final episode. The editing is fluid, but Arthur Reinhart's cinematography - pointlessly pretty where the film should get right down in the mud with its protagonists - lets the project down a bit. Still, that would add up to a pass. It's the writing that really undermines the whole affair.

This is how producer Leslie Greif describes the theme of the miniseries: 'I felt that the story was bigger than just the Hatfield and McCoys. It

talked about the tragic cycle of violence that's been throughout all of

man's history, whether it's feuding with your neighbo[u]rs over the height

of trees or the Crips and the Bloods or the PLO or the IRA or just a

bully where both people are picking sides.' That's the problem: for the sake of 'all of man's history', Greif ignores the specificity that would have given her story shape. All that time and money could have been used to chronicle the feud before a backdrop of identity, honour and social

change in late-nineteenth-century Appalachia. Instead, Hatfields & McCoys dispenses with a sense of place, giving us cardboard cutouts, a cliché-storm plot and unending tedium in front of a vast nothingness.

It's all stock characters wandering about, occasionally shooting each other. 'Greetings, fellow symbol of the human condition! I am angry. I am sad,' they might as well say in the worst Hollywood Southern writers Ted Mann and Ronald Parker can muster. Female characters fall into a Madonna-whore pattern so rigid it would have been considered unseemly in the silent film

days. (Roseanna is good and pure, while her cousin Nancy is sexually rapacious and wicked. And so it goes.) Johnse Hatfield obeys his father without fail, then whinges about the injury done to his precious conscience: I sure do hate him, but I the script doesn't indicate whether I'm supposed to. The closest Hatfields & McCoys has to narrative arcs is that the 'good' patriarch - the austere, puritanical Randall McCoy - becomes an embittered alcoholic, while his mercenary counterpart is eventually redeemed.

All of that sinks the miniseries and most actors sink with it, delivering wooden, one-note performances. But there are exceptions, and the series' Emmy wins are right on the money. Tom Berenger, a grossly underrated character actor, is an absolute delight: impious and deadly yet jovial, his Jim Vance is a mesmerising old-school badass. Ronan Vibert is amazingly smarmy, while Andrew Howard's hammy villainy is almost infinitely enjoyable. It's Costner, though, that surprised me the most. The man's made a career of a certain brand of amiable dullness, but here he does great work as a cold and calculating man who nevertheless loves his family enough to know when the time has come to end the feud. They're worth watching, those guys. I just wish they weren't stuck in such a rote, joyless exercise.

Showing posts with label American Civil War. Show all posts

Showing posts with label American Civil War. Show all posts

Saturday, 16 February 2013

Cardboard Appalachia

Wednesday, 18 July 2012

The patriarchal imagination of Doug Wilson

Trigger warning: this post discusses rape, slavery and genocide apologia.

Last night over at The Gospel Coalition, Jared Wilson posted an excerpt from Doug Wilson's Fidelity: What It Means To Be A One-Woman Man. 'Outrage' is often used to describe the sort of reaction the post provoked, but 'hurt' is just as apt. The Wilsons wounded their brothers and sisters, and when people expressed their hurt they belittled them and told them to 'retake their ESL class'. It's worth quoting that Doug Wilson excerpt in full:

A final aspect of rape that should be briefly mentioned is perhaps closer to home. Because we have forgotten the biblical concepts of true authority and submission, or more accurately, have rebelled against them, we have created a climate in which caricatures of authority and submission intrude upon our lives with violence.

When we quarrel with the way the world is, we find that the world has ways of getting back at us. In other words, however we try, the sexual act cannot be made into an egalitarian pleasuring party. A man penetrates, conquers, colonizes, plants. A woman receives, surrenders, accepts. This is of course offensive to all egalitarians, and so our culture has rebelled against the concept of authority and submission in marriage. This means that we have sought to suppress the concepts of authority and submission as they relate to the marriage bed.

But we cannot make gravity disappear just because we dislike it, and in the same way we find that our banished authority and submission comes back to us in pathological forms. This is what lies behind sexual “bondage and submission games,” along with very common rape fantasies. Men dream of being rapists, and women find themselves wistfully reading novels in which someone ravishes the “soon to be made willing” heroine. Those who deny they have any need for water at all will soon find themselves lusting after polluted water, but water nonetheless.

True authority and true submission are therefore an erotic necessity. When authority is honored according to the word of God it serves and protects — and gives enormous pleasure. When it is denied, the result is not “no authority,” but an authority which devours.

– Douglas Wilson, Fidelity: What it Means to be a One-Woman Man (Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 1999), 86-87.Rachel Held Evans has done a beautiful job of unpacking why this is vile, overt misogyny that does not even bother to hide behind standard complementarian weasel words. J.R. Daniel Kirk, too, gets straight to the point:

[W]hen you sexually conquer someone, this is rape. The connection Wilson draws is too much on target: he has, in fact, described all sex as an act of rape. It is therefore not surprising that he sees such a connection between rape outside of marriage and not finding the sort of satisfaction that he suggests is coming to men in their exploits of power.Wilson's argument is this: sex ought to consist of men penetrating, planting, conquering and colonising (i.e. rape) and women receiving, surrendering and accepting. When it does not - when it becomes an 'egalitarian pleasuring party' - then men will act out their God-given manhood in unacceptable forms of rape, and women will partake of perverted varieties of sexual submission. This is somewhat at odds with reality, of course. One of the major victories of the women's movement, after all, was the outlawing of marital rape.

The Wilsons' response to their critics is generally not worth the blog space it's written on. They insist that they've been misunderstood, but fail to explain what they mean. They accuse their critics, in the passive-aggressive 'Why do they hate us?' fashion of the faux martyr, of trying to twist their words. Jared, in fact, withdraws to affirming 'marital sex that is mutually submissive' while pretending not to have retreated.* Doug's 'explanation' of his choice of words takes the cake, though:

“Penetrates.” Is anyone maintaining that this is not a feature of intercourse? “Plants.” Is the biblical concept of seed misogynistic? “Conquer.” Her neck is like the tower of David, and her necklace is like a thousand bucklers. “Colonize.” A garden locked is my sister, my bride. C’mon, people, work with me here.Here we have a response that ignores the existence of non-penetrative sex because it would throw Wilson's argument that sex is necessarily about domination into disarray; that attempts to shame critics by wielding the Bible as a sledgehammer; that makes two references to the Song of Songs which significantly distort the actual trajectory of mutual pursuit found in that wonderful erotic poem. And by feigning incomprehension, Wilson continues men's long and ignoble history of insisting that women who criticise them are irrational or 'emotional'.

It's not just women, however, that Wilson thinks are uppity. In the video at the top of this post, Wilson identifies with the values of the Confederacy, such as states' rights - as if those were more than an expedient to prevent the federal government from interfering with slavery; and he holds that slavery should have been abolished by parliamentary processes rather than war - as it might well have been had the Southern states not seceded and attacked the North precisely to preclude that possibility. Wilson reveals a blindness to really existing institutions of power and privilege, be they patriarchy or slavery, that is born of being a white Christian man and not listening to people who aren't.

What connects Wilson's neo-Confederate tendencies to his rabid pro-patriarchalism isn't just his evident desire to return to the good ol' days of c. 1850. As Grace at Are Women Human? points out, Wilson's apologia for both rape and slavery is linked by his vision of a society in which white men benevolently rule over everyone else. White male domination is thus at the heart of Wilson's belief system. This is not, I hardly need to stress, an orthodox view of Christianity - although some people who think like Wilson use the cross too, usually by setting it on fire.

Wilson's choice of words - penetration, planting, conquest, colonisation - is the naked language of imperialism. He projects the seizure of physical space from indigenous people onto female bodies. Here as there, violence is glorified as the expression of true manliness and justified by 'planting', which has excused occupation and genocide from the Americas to the West Bank. By casting women as a dark continent that must be subdued and made to flourish by white Christian men, Wilson doesn't just other women: he reveals his fear of them. If left unconquered, uncolonised and unpenetrated, they might run amok and threaten his privilege.

It works the other way round, too, for 'penetration' is a metaphor drawn from patriarchal sex that imperialism projects onto the places it wishes to consume and the people who live there. That actual, physical rape occurs in this context is hardly surprising. The language of 'penetration' that robs women of agency and humanity does the job just as well when dusted off and applied to indigenous people and their lands. In gendering to-be-conquered people feminine, imperialist discourse reveals its roots in patriarchal society.

This has, I fear, been something of a long, rambling post. It has not been temperate. It's hugely encouraging to see how many Christians have stood up to Wilson's rape fantasies. We can be confident, I think, that increasingly those who grant the views of Wilson and his ilk shelter - those like The Gospel Coalition - aren't just wrong. They're also in the minority.

*Jared Wilson mostly quoted Doug Wilson approvingly without adding much, and now he is out of this saga.

Labels:

American Civil War,

Christianity,

empire,

evangelicalism,

gender

Thursday, 25 August 2011

Instant awesome, just add armour (The Great War: Breakthroughs)

Welcome back for the final round of alternate-history Great War mayhem! I complained at length that Walk in Hell, the previous volume in the series, spent six hundred pages spinning its wheels, but I knew the pay-off was rumbling over the hill, blowing smoke and soot, blazing away with cannon and machine guns. Oh yes, it's barrel time!

'Barrels', indeed: for Turtledove had the ingenious idea of renaming those steely beasts of battle, although the British term, 'tanks', is also sometimes used. They turn out to be crucial in deciding the outcome of the war, and boy, do I like how Turtledove goes about this. By War Department doctrine, the US deploy barrels evenly spaced along the front. General Custer, commander of First Army in Tennessee, defies this not out of great strategic insight, but because of his oft-proved incompetence.

Custer, you see, has been well established as your standard 'attack, attack, attack' commander since How Few Remain. In previous books, First Army has suffered terrible losses thanks to his pigheaded offensives against entrenched enemy positions. Now, however, Custer seizes on the unorthodox ideas of Colonel Irving Morrell (a character I like, with a name allusion I can't stand), who wants to deploy barrels en masse and drive armoured spearheads through enemy lines. Presented with the opportunity to wield a really large sledgehammer against the Confederacy, Custer assents, First Army breaks through, and the Confederate defence of Nashville is shattered.

The descriptions of armoured warfare are very much the best part of Breakthroughs, giving the volume a dynamism sorely lacking in Turtledove's previous effort. I mean, how awesome are barrels? (Don't answer that. Obviously we should abolish war as soon as possible, &c.) But it's not just in Tennessee that the front is moving again. In the eastern theatre, the Confederates are driven back into Virginia. In the Trans-Mississippi and Canada, too, Entente forces are losing ground rapidly. As the war draws towards a conclusion, the Confederates are attempting to negotiate peace with honour, while Roosevelt is pushing for a harsh diktat.

The characters are stronger, too. In American Front, Gordon McSweeney was part annoying, part offensive to me as a Christian; in Breakthroughs, he is badassery incarnate in one man. He singlehandedly captures and kills dozens of enemy soldiers, destroys a tank with a flamethrower and eventually performs a crazy-awesome feat of valour I dare not spoil. All this while being utterly insane. Flora Hamburger, whose run for Congress was one of the redeeming features of Walk in Hell, is sadly given little to do here.

But let's talk about artillery sergeant Jake Featherston, a man who is coming to the fore as peace approaches. He's quite an unpleasant human being, a mixture of frustration, envy, and murderous hatred; but his scenes are among the highlights of the book. His futile attempts to stem the Yankee sweep into Virginia render him increasingly embittered, and he begins to write a book blaming the political class and the blacks of the Confederacy for defeat. All this is compelling enough: the trouble comes from the fact that it's perfectly obvious from our timeline where his path leads. This parallelism, which Turtledove is too fond of, is a real problem, breaking suspense in advance.

Breakthroughs is a high point for the series; but just like the peace forged between the American nations, it carries within it the seeds of future trouble. By the end of the book, similarities between the future trajectory of the Confederacy and certain European nations are already heavily implied. To me, that goes against the spirit of alternate history: the author should genuinely spin his timeline, not tether it to real history. But for now it's all good; let us bask in the glory of Turtledove's final Great War novel, and let tomorrow worry about itself.

P.S. As I'm moving and probably won't have access to further novels in the near future, I'm putting this series on hiatus for now, but will get back to it as soon as I can.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Walk in Hell

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Sunday, 21 August 2011

The Great War: Walk in Hell (Southern Victory Series, Part Four)

Middle instalments of trilogies are always a tricky business. The first part has all the interesting set-up, the finale boasts all the pay-off: middle instalments mostly develop themes. But there is quite honestly no reason Walk in Hell should be such an awful slog: no reason except, perhaps, that a stalemate must feel like a slog. In which case Harry Turtledove is a genius, deliberately boring his readers, as Bret Easton Ellis does in American Psycho, to make them feel the tedium-cum-horror of the world they inhabit. Somehow, though, I doubt it.

Walk in Hell begins with the black labourers of the Confederacy rising in Red rebellion. Even though Turtledove fails to develop a version of Marxism more suited to the situation of Southern blacks (compare, for example, Lenin's adjustments to orthodox Marxism for Russian conditions), it's still quite a premise. Unfortunately, the author doesn't exploit the idea: the socialist republics fizzle so quickly that there is no chance to explore life in the envisaged new society.

Elsewhere, the fronts are barely moving. The USA are very slowly advancing everywhere, while the war effort takes an ever-greater toll on civilian life throughout 1916. Characters are being developed and in some cases introduced - Paul Mantarakis stops a bullet in Lower California and is replaced as a point-of-view character by Gordon McSweeney, an insane Presbyterian whom I very much look forward to discussing in my review of Breakthroughs.

This deadlocked state of affairs is of course historical, but Turtledove is too obviously inspired by the Western and Italian (in the case of the Canadian Rockies) Fronts of the real-life First World War. Although Turtledove pays lip service to the less than ideal supply situation in the Trans-Mississippi, fronts should move much more rapidly in the Canadian Prairies as well as Arkansas, Sequoyah and Texas, as they did on the Eastern Front in our timeline. But of course, if the author did that, Canada would be cut in half and knocked out of the war too quickly for dramatic purposes: the Rule of Drama may be invoked here.

I'd also like to take the opportunity to complain obnoxiously, as one does, about one of my greatest bugbears when it comes to Turtledove. For, you see, the author's eagerness to write sex scenes is matched only by his total inability to make them in any way sexy. (Using the term 'chamberpot' in your sex scenes - repeatedly! - is not a good idea.) Given that sex is technically unimportant to the plot, one would be grateful for mercy.

But it's not all bad. There are lovely little touches all over the place. For example, there is an extra named Moltke Donovan: his name is (unusually for Turtledove) never commented upon, but is precisely what we might expect in the world the author has created. And we should not be too hard on Walk in Hell for spinning its wheels for six hundred pages: it's build-up for one hell of a final instalment.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Breakthroughs

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Sunday, 10 July 2011

The Great War: American Front (Southern Victory Series, Part Three)

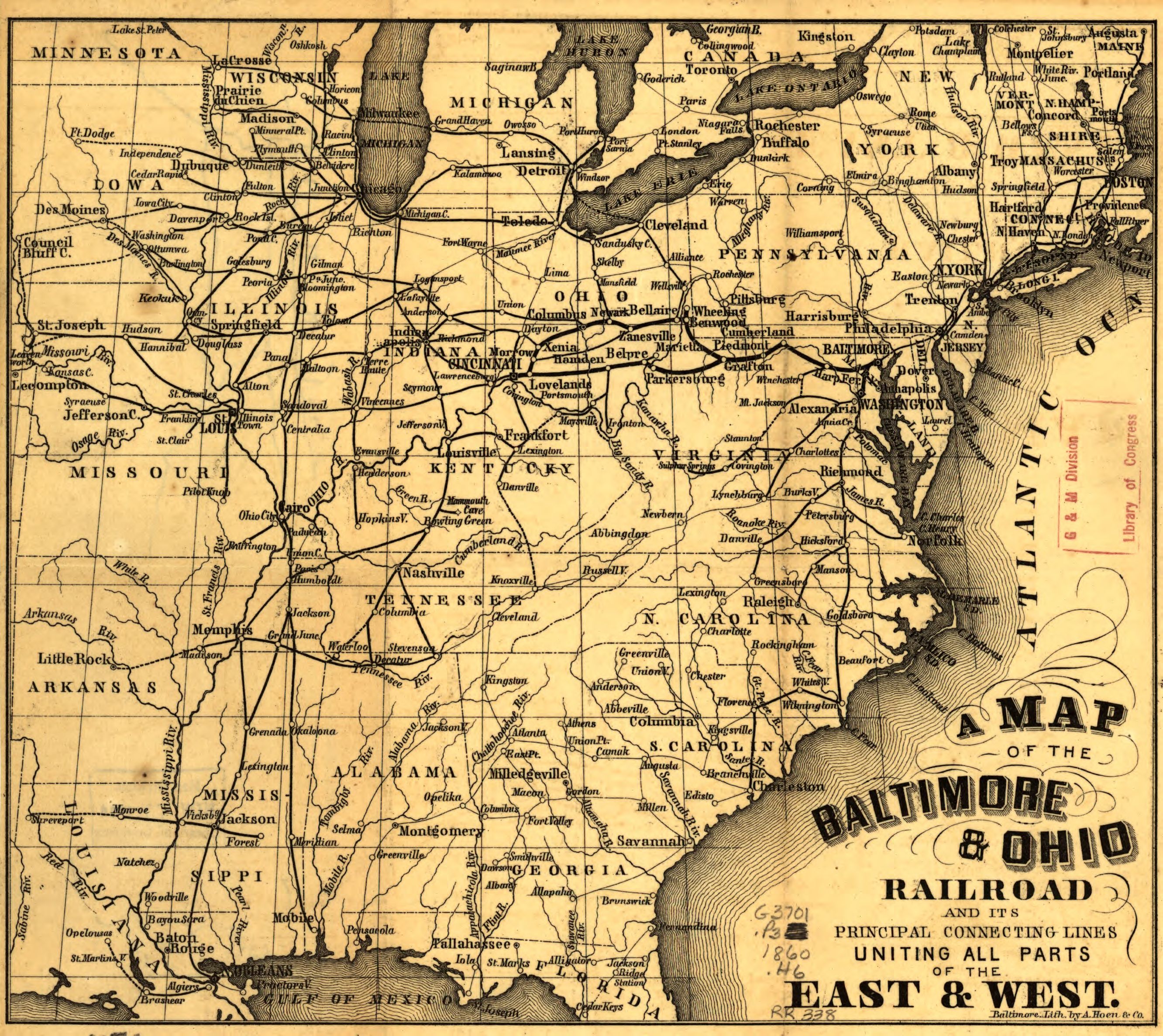

|

| North America in 1914 |

There's a strong argument that the First World War could easily have ended very differently. If the German High Command had not diverted forces eastwards that were later missed during the Battle of the Marne - if Italy or later the United States had remained neutral - if the German spring offensive of 1918 had succeeded... The consequences of Central Powers victory would have been momentous.

So it's no surprise that Turtledove's opening scenario would knock something as precarious in real life as the First World War off balance completely. As you'll remember, in Turtledove's timeline the Confederacy defeats the United States in 1862 and again in 1881 in a rematch over the Confederate purchase of Sonora and Chihuahua from Mexico. Fast forward to 1914, and relations between the two American powers are frosty as ever. The USA, who have maintained close relations with the German Empire since the 1880s, are part of the Central Powers, while the CSA join Britain, France and Russia in the Quadruple Entente. When war breaks out, both powers enter the fray, with the USA having to fight Canada and Britain in the north and the Confederates in the south.

As argued here, this scenario is quite problematic. Conducting an arms race against both Germany and the USA would have overstretched Britain impossibly, and it therefore seems likely Britain would have sought an accommodation with one of these powers. Historically, England decided to remain neutral towards the United States, while planning for a confrontation with Germany; there is no reason why this should be different in Turtledove's timeline.

Indeed, the cost of conducting a land war along a border of almost 4000 miles would have convinced any British policy-makers to maintain neutrality towards the United States at almost any cost. Not to mention that the CSA could provide no benefit to Britain in a European war unless the USA were neutral, freeing up CS resources - an unlikely scenario at best.

I disagree, however, with the notion that Britain would have allied herself with the USA against the CSA. It seems more likely to me that British diplomacy would have been aimed at stopping the war from spreading to North America entirely through neutrality towards the USA, which would have forced the CSA into neutrality, since they could never have fought the North by themselves. Like Britain, Germany would have no incentive to ally itself to the Confederate States.

In Turtledove's timeline, the most likely scenario therefore seems peace in North America, or else an opportunistic US-British alliance in which the US could have attacked the South with impunity. But of course, Turtledove is at this particular point not interested in historical plausibility: what he wants is a massive land war in North America, and his scenario gives it to him.

Like How Few Remain, The Great War: American Front is told through a number of characters. But this time there are rather more of them and they're entirely fictional. That's not without its problems, unfortunately, for Turtledove is on rails here: he feels the need to create allohistorical analogues for people and events that do not occur in his timeline. You get one guess, for example, to figure out who 'Irving Morrell' (say it out loud), US tactician making his name with innovative tactics of surprise and speed on the

Generally the oppressed characters (women, blacks, and civilians living under military occupation) are far more interesting than the relatively tedious middle-class white men. That rule of thumb is not without its exceptions: Anne Colleton, as a Scarlett O'Hara expy, is possibly my least favourite character. The opposite goes for Flora Hamburger (gee, I wonder which real person's name Turtledove might be inspired by here), socialist agitator in New York, who I can really root for.

Unfortunately, American Front is also somewhat less well written than How Few Remain, to put it mildly. I present you with the very first paragraph of the book:

The leaves on the trees were beginning to go from green to red, as if swiped by a painter's brush. A lot of the grass near the banks of the Susquehanna, down by New Cumberland, had been painted red, too, red with blood.Someone please make him stop. Clumsy exposition is another massive problem:

'General McClellan, whatever his virtues, is not a hasty man', Lee observed, smiling at Chilton's derisive use of the grandiloquent nickname the Northern papers had given the commander of the Army of the Potomac. 'Those people' - his own habitual name for the foe - 'were also perhaps ill-advised to accept battle in front of a river with only one bridge offering a line of retreat should their plans miscarry.'This sort of unspeakably awful thing goes on for six hundred pages, I'm sorry to say. Turtledove was perhaps ill-advised to include in-text exposition rather than append some basic information and allow the reader to figure out a lot of facts, rather than constantly attempting to show how much research he's done. A sense of strangeness, rather than thudding exposition at every turn, would surely serve an alternate history novel well.

So, then: Harry Turtledove is a pretty bad writer. But I'm not ashamed to say I'm devouring this series all the same. It's far more plausible than is usually the case with alternate history, it's aware of social and political issues (especially blacks' struggles) to an uncommon extent, and it offers really fascinating breaks from our timeline and occasional wonderful touches (of which more next time). I do hope it picks up a bit, though.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: Walk in Hell

The Great War: Breakthroughs

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Thursday, 7 July 2011

How Few Remain (Southern Victory Series, Part 2)

This post follows my introduction to the general setting of Harry Turtledove's alternate history timeline in which the Confederacy wins the American Civil War in 1862.

In the Anglosphere at least, Southern victory in the American Civil War is one of the most popular historical 'What ifs?', beaten out only by a certain other scenario which Godwin's law won't let me mention. So Turtledove had to choose an original approach if he wanted to make his mark. That he did it twice is to his credit.

In The Guns of the South (1992), time-travelling white supremacists armed a beleaguered Robert E. Lee with AK-47s for the 1964 campaign, leading to a Confederate victory. So when How Few Remain was published in 1997, Turtledove was at pains to point out that it was not a sequel to the earlier book, but rather the beginning of an entirely different timeline: one in which the Confederacy won 'through natural causes', as outlined in my earlier post.

How Few Remain picks up the story in 1881. The Union and the Confederacy remain rivals. The CSA have maintained strong ties with their allies Britain and France while also taking Cuba and Puerto Rico from the fading Spanish Empire. The USA, by contrast, have crushed the resistance of the remaining Indians but have not taken Alaska from the Russian Empire. But trouble starts a-brewin' when the CSA offer to buy the provinces of Sonora and Chihuahua from a perpetually broke Mexican Empire. (In Turtledove's timeline, French intervention in Mexico was successful, leaving a feeble Emperor Maximilian on the throne.)

You see, buying up Sonora and Chihuahua would give the Confederates access to the Gulf of California and raises the prospect of a Confederate transcontinental railroad. The USA, keen to (a) keep the Confederacy out of the Pacific and (b) give the 'Rebs' a good thrashing to make up for the War of Secession, soon declare war. Britain and France both join their Confederate allies. President James Longstreet, a prudent politician, even agrees to manumit the Confederacy's slaves in return for European support.

Like all the books in the Southern Victory series, How Few Remain is narrated in the third person through a number of point-of-view characters; but unlike later books, there are fewer of them, and they're all well-known historical characters. There's Abraham Lincoln, socialist orator and former president of the US; Thomas 'Stonewall' Jackson, general-in-chief of the Confederate States Army; Samuel Clemens, newspaper editor in San Francisco; Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, journalist, and orator; George Armstrong Custer, US cavalry colonel; Theodore Roosevelt, an independently wealthy landowner in Montana; Jeb Stuart, commander of the Confederate forces in the Trans-Mississippi; and Alfred von Schlieffen, the German Empire's military attaché to the United States.

These are really fascinating characters, and Turtledove does a really good job of showing how a different outcome in 1862 put them on alternate paths. As a socialist, I'm obviously rather pleased with Abraham Lincoln's adoption of Marx (but not poor, perpetually forgotten Engels, apparently). Because they're based on historical figures, Turtledove has little trouble creating rounded, compelling characters. And he finds their voice, too: I'm especially pleasantly surprised by his invocation of Sam Clemens's journalistic style.

Most characters here are the sort of people you can root for, too: that goes especially for Lincoln, Douglass and Clemens and not at all for Custer, who is stupid, vainglorious, arrogant and selfish, but quite fascinating all the same. The Ensemble Darkhorse is Alfred von Schlieffen, who's a genuinely likeable character despite coming up with the military plan that bears his name. Turtledove must be criticised, however, for his frequent and annoying use of Poirot Speak: foreign characters fall back on their native language for simple words, not coincidentally those the monoglot reader is most likely to know. This tends to render them a little ridiculous.

All in all, How Few Remain presents a thoroughly plausible alternate timeline with largely rounded and compelling characters, and with a warm humanity suffused throughout: Turtledove never cushions the systemic inhumanity of slavery. A good start, then: let’s see if he can keep it up in The Great War: American Front.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Walk in Hell

The Great War: Breakthroughs

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Wednesday, 8 June 2011

Southern Victory, Part One: Setting the scene

I'm a sucker for alternate history. It was only a matter of time, then, before I began reading Harry Turtledove, the 'master' of the genre. Turtledove has written some zany stuff (aliens in the Second World War! Confederate AK-47s! Byzantines and magic!), but it'll be no surprise I was most interested in what is usually dubbed the Southern Victory series or Timeline-191, in which the Confederate States win the American Civil War in 1862 and survive to participate in the major events of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

I hope to review the books one by one as I read them (I've read the first two, How Few Remain and The Great War: American Front). For this post I want to explore Turtledove's setting. I'll do some gushing here as I'm quite enamoured with its general realism, but of course there are also criticisms. You'll forgive the geekery in what follows; it's par for the course.

Unlike the many alternate histories of the Civil War that hinge on a different outcome at Gettysburg, Turtledove's timeline diverges in 1862. This is undoubtedly a correct choice. As Marx and Engels (yes, really; they were astonishingly competent on military matters) argued throughout the war, the key to Union victory was always the Western Theatre, that is control of Tennessee followed by an invasion of Georgia, accomplished by Sherman in 1864. By the time of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, the Union already controlled much of Tennessee as well as the Mississippi; accordingly, the Confederates were in very deep trouble that could only partially have been alleviated by victory at Gettysburg. The CSA's best hope was an early knockout blow in the east before Federal forces could make crucial gains in the west. That was precisely Lee's strategy, and the reason he invaded the North in both 1862 and 1863.

Historically, Robert E. Lee split the Army of Northern Virginia into three parts when he invaded Maryland in the late summer of 1862. The order detailing the precise troop deployments was lost by a courier and, by sheer chance, picked up by Federal troops, permitting the Union to defeat Lee at Antietam/Sharpsburg on 17 September. In Turtledove's version of events Order 191 is never lost, Lee is subsequently able to destroy the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Camp Hill in Pennsylvania and goes on to occupy Philadelphia. This catastrophic defeat forces the US to divert forces from the west, allowing Braxton Bragg's Confederates to occupy Kentucky. Britain and France extend diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy, forcing Abraham Lincoln to negotiate the end of the war.

In the settlement the Confederacy retains Kentucky, but accepts that western Virginia (which soon becomes the Union state of West Virginia), Missouri and Arizona will remain in the Union. The US subsequently emancipate their remaining slaves (some 200,000, I believe). I'm pleased with how relatively low-key this is: no overwhelming Confederate victory leading to, say, all the border states joining the CSA. It's perfectly clear throughout the novels that the United States are and remain by far the stronger of the two powers. At the same time, Turtledove makes the important point that Confederate victory was a very real possibility - something that Marxists of the orthodox variety may be loath to admit since the US were undoubtedly the more 'historically advanced' of the two parties. (It's very clear from their articles that Marx and Engels supported the North not because it was more 'advanced' but because of the horrors of slavery.) But in 1862 the CSA undoubtedly had better generalship, and this created a window of opportunity before the North could bring its crushing numerical and industrial superiority to bear.

In jumping straight from 1862 to 1881, the first novel, How Few Remain, sidesteps a number of historical questions. I'm particularly interested in what might have happened to the many thousands of slaveholders in the border states: would some of them have chosen to move to the Confederacy? I can imagine a scheme of the Confederate government resettling slaveowners and buying up slaves to compensate those expropriated in the US, which would have simultaneously stimulated the ailing slave economy of the South. Someone who ought to have been a point-of-view character in How Few Remain is Jesse James, for his life - as the scion of a slaveholding Missouri family who first went to war in 1864 - would have been radically altered by Turtledove's alternate history. Would the James family have returned to their native Kentucky? What an opportunity for fanfic!

Turtledove's other interesting general contention is that continuing hostility between USA and CSA would have involved the European powers in North America in a way that did not happen in our timeline, eventually tying both powers into European alliance systems. That seems quite plausible to me: the Confederacy in particular would have needed strong allies to survive.

So, reviews to follow!

In this series:

How Few Remain

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Walk in Hell

The Great War: Breakthroughs

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)