Wednesday, 24 June 2015

Every chapter I stole from somewhere else

The vagueness allows Stoker to gloss over a detail: Vlad III was the Voivode of Wallachia, a mostly lowland principality to the north of the Danube in present-day southern Romania. Transylvania, where Stoker's count has his home, is an entirely different (albeit neighbouring) region, a part of medieval Hungary. Stoker rightly thought the legend of Vlad the Impaler was too good to pass up, so he fudged his history a bit. And we don't mind because he did it in the service of a novel that presents, despite awkward, overheated prose and reactionary politics, a good story.

You know what's pretty much the opposite of a good story, though? Dracula Untold. Seriously.

In the fifteenth century, Vlad Dracula (Luke Evans) rules the principality of Transylvania [sic] as a vassal of the Turkish Empire. When the Turkish envoy Hamza Bey (Ferdinand Kingsley) demands that 1,000 Transylvanian boys - including Vlad's own son (Art Parkinson) - be turned over to the Turks for training as Janissary soldiers, as Vlad himself was, the Prince is distraught. After his attempt to plead personally with Sultan Mehmed II (Dominic Cooper) fails, Vlad refuses to budge, killing the Ottoman party tasked with bringing back the hostages and plunging Transylvania into war.

Realising he lacks the strength to fight off the Turkish army, Vlad visits the monstrous denizen of a mountain cave (Charles Dance), who lends him his vampiric powers. If Vlad manages to resist the craving for human blood for three days, he will return to his normal human self. If he gives in, however, he will become an immortal bloodsucking fiend forever. Realising he has little choice if he is to save his people, Vlad accepts the wager and turns into a superpowered, if increasingly sinister version of himself.

It would be difficult to argue that Dracula was exactly crying out for an origin story. (Not impossible: I for one would love to see a historical fantasy series set in the fifteenth-century Balkans on TV.) But dredging up the making of a hero has been the fashionable way to rekindle audience interest in washed-up properties since Batman Begins in 2005 (Sam Raimi's 2002 Spider-Man was an origin story too, but saw no need to go on about it). Christopher Nolan's Batman films also gifted us the flawed, introspective hero that's spread like measles throughout corporate filmmaking. It's an approach that works fantastically for Batman, but for other characters - like, it turns out, Dracula - it's potentially lethal.

Combine a cookie-cutter origin story, a dark and brooding protagonist and the burden that Dracula Untold is the first film in the Marvel-aping rebooted Universal Monsters cinematic universe, and you have a recipe for disaster. The franchise angle forces the film to end on a bizarre and awful modern-day scene, while its slavish paint-by-numbers approach causes Dracula Untold to run into a serious problem: namely, that Dracula's appeal isn't as a hero, glum or otherwise. What people pay for when going to see a Dracula film is a charismatic immortal villain. Attempting to tell the story of how a virtuous aristocrat became an undead monster isn't impossible. But it would at the very least require the courage to make your protagonist, you know, evil by the end of the film. Instead Evans's Dracula stubbornly remains the same reasonably decent concerned dad, whether he's celebrating Easter with his adoring subjects or slaking his thirst on the blood of thousands of mooks. Worrying about audience sympathies causes writers Matt Sazama and Burk Sharpless to simply give up on character development entirely.

But then, Dracula Untold isn't trying to tell the story of how a monster came to be because, apart from the most cursory of nods, it isn't a horror film. It's a superhero picture, if the shameless and uninspired cribbing from the conventions of the DC and Marvel films of the last decade didn't give that away, and a particularly asinine example of the form: cardboard villains, tedious powers and an adherence to formula so rigid that it chokes whatever life should be there right out of the film. There's even a scene in which silver fills in for kryptonite. In the face of so much formula, who could blame first-time director Gary Shore for falling asleep at the helm?

The film borrows extensively from what has come before. The opening scene, for example - in which voiceover narration explains to us scenes of boys being put through gruelling military training that includes a lot of whipping - is a bafflingly close retelling of the start of 300. Frank Miller's anti-Persian tirade provides the backbone for much of what follows, although Dracula Untold lacks the earlier film's full-throated fascist propagandising. Its Turks are mostly uninspired generic baddies, although the ominous crescents on their tents and repeated references to their menace to the capitals of Christian Europe are quite enough, in the age of Anders Behring Breivik, to qualify as grossly irresponsible. The film is, not to put too fine a point on it, racist trash, its obvious brainlessness aggravating rather than lessening its offensive pandering to fashionable prejudice.

Then there's Vlad's leading of the Transylvanian people to the safety of a monastery in the mountains, borrowed among other antecedents from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. It's indicative of the film's gross lack of any sense of scale: the whole of Transylvania seems to consist of at most a couple of hundred people located in a single castle, and the entire war between Vlad and the Ottoman Empire is over in the required three days (in the real world, meanwhile, a medieval army would take well over a month to cover the distance between Istanbul and Vlad's historical capital of Târgoviște).

Nothing in Dracula Untold, in short, feels like it takes place in a plausible approximation of the real world. It looks fake, too: I left the film convinced its backgrounds were entirely computer-generated only to find out it was shot on location in Northern Ireland - a popular filming location in the age of Game of Thrones though not, alas, one famed for its scenic mountain ranges. The cold metallic colour palette chosen by cinematographer John Schwartzman seems an odd fit, too, for the backwoods medievalism the story would seem to require.

It's tired hackwork, is what it is, and the utterly uninspired performances reflect this. Evans tries, but he has literally nothing to work with; of all the people onscreen, only Charles Dance manages to have some fun with a scenery-chewing, genuinely effective performance. Say what you will about corporate filmmaking, but it guarantees at least a certain professionalism. Dracula Untold, alas, has literally nothing to offer beyond that base amount of competence. It's a product so soulless that it's difficult to be upset no-one involved in it managed to care.

Saturday, 28 April 2012

With a little help from my friends

At a S.H.I.E.L.D. facility Thor's adopted brother Loki (Tom Hiddleston) steals the Tesseract, a potentially infinite energy source, and brainwashes Agent Clint 'Hawkeye' Barton (Jeremy Renner) and Dr Selvig (Stellan Skarsgård) into becoming his minions. In response, Director Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson) decides to reopen the Avengers Initiative and gradually recruits Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.), Captain America (Chris Evans), Thor (Chris Hemsworth) and Dr Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo) to his cause with the help of Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) and Agent Coulson (Clark Gregg). It soon transpires that Loki has made a pact with the alien race of the Chitauri, who will help him conquer Earth.

The Iron Man films, Thor and Captain America: The First Avenger established their respective characters well enough for Whedon to not have to worry about them, which must have been a relief in an ensemble piece. Three challenges remained, I think: the Incredible Hulk, left on shaky ground by two underwhelming previous films; Natasha Romanoff/Black Widow, little more than window-dressing in Iron Man 2; and Hawkeye, likewise little known among the general public. That it works so well isn't just to Whedon's credit. Mark Ruffalo is a terrific Bruce Banner, finally giving us, at least in embryo, the Hulk film we were waiting for; Renner's natural charisma carries off a somewhat bland hero; and Black Widow is so much better written than the femme fatale routine Justin Theroux put her through that she hardly seems like the same character.

Compared to the intense character work on these three the other Avengers cruise along, and why shouldn't they? Obvious pitfalls are avoided: the film is remarkably light on jokes regarding Captain America's disconnect with the modern world, for example, and treats Cap as an emblem of old-fashioned virtue above all. If we can fault the way The Avengers handles character, it's only in its distressingly keen sense of their respective popularity. At times, the film turns into Iron Man & Friends, but favouritism never overwhelms balance entirely, and the thoroughly pleasant surprise of the love lavished upon minor characters makes up for whatever focus on Robert Downey Jr.'s increasingly tired shtick there might be.

'Balance', in fact, describes The Avengers rather well. It is an extraordinarily polished, carefully weighed film, almost entirely free of rough edges; but where it never plummets, it hardly soars either. Whedon is a better director of narrative than director per se, and in consequence there are a number of extraordinarily effective shots going from character to character, with nary a memorable image to be seen. In truth, I entered terminal superhero fatigue roughly two years ago, and The Avengers did not lift me out of that. But I spent two and a half entirely agreeable hours at the cinema, and for an ensemble film of this size to even work on that level is an unlikely success in itself.

Friday, 14 October 2011

Gotham City always brings a smile to my face

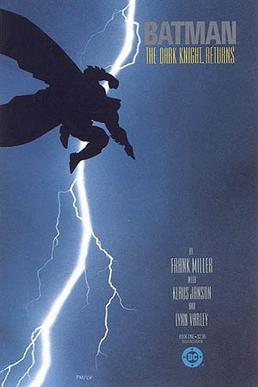

Richard Donner's Superman (1978), released in the wake of Star Wars (1977), introduced the superhero blockbuster and dominated the eighties with its sequels, but during that decade films and comic books were out of sync: on the page, the Dark Age was dawning with Alan Moore's V for Vendetta (1982-89) and Watchmen (1986-87) as well as Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Batman: Year One (1987).* Tim Burton's Batman (1989), the first really serious superhero film, changed that and kicked off the first wave of comic-book adaptations. (The last film in the series, 1997's Batman & Robin, killed off that wave as well as its own franchise.)

Twenty-odd years on, what was highly revisionist at the time has become 'classic'. The plot begins with Batman still a rumour, scoffed at by the less superstitious of Gotham's criminals. The new district attorney, Harvey Dent (Billy Dee Williams), is preparing to challenge the criminal empire of Carl Grissom (Jack Palance), who is struggling with his overly ambitious lieutenant Jack Napier (Jack Nicholson). Grissom double-crosses Napier, sending him to raid a chemical plant at night and ordering corrupt policeman Eckhardt (William Hootkins) to ambush Napier's men. In the ensuing struggle, Batman disarms Napier, who falls into a vat of green acid and is believed dead.

Napier, however, has miraculously survived both the acid and the ensuing botched plastic surgery ('You understand that the nerves were completely severed, Mr Napier. You see what I have to work with here...') and becomes the villainous Joker in the film's strongest and most iconic scene. After murdering Grissom, he plots to poison Gotham City's hygiene products with Smilex, which will kill the victim while fixing their face in a horrid rictus grin, in the run-up to the city's bicentennial celebrations. (Incidentally, this provides an excellent way to guess at Gotham's location: with a foundation date of 1789, the city is presumably in Ohio, the Great Lakes region, or the north-eastern Atlantic coast.) The Joker also pursues photographer Vicki Vale (Kim Basinger), who is dating wealthy Bruce Wayne (Michael Keaton).

It's a Joker picture, then, even more so than The Dark Knight (2008): Nicholson takes top billing, and Batman functions almost solely as his foil. The focus on the Joker's origin sets the 1989 film apart from the latest Christopher Nolan picture, which has Batman's nemesis appear from nowhere. Giving a definitive origin story for the Joker was controversial among fans (Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore had given a possible, but deliberately ambiguous origin the previous year). But it works: Nicholson's Joker is a crazed villain even before being disfigured (his pre-murder one-liner, 'Have you ever danced with the devil in the pale moonlight?', goes back to his ordinary criminal days), suggesting the Joker is merely a useful persona.

Nicholson gets the best setpieces, too, the most famous perhaps his dance routine desecrating an art gallery to the sounds of Prince's 'Partyman' supplied by a boombox-carrying goon ('I am the world's first fully functioning homicidal artist!'). The actor goes all out on the craziness, and while Nicholson's shtick can be irritating - witness his horrendous overacting almost derail The Departed (2006) - it's perfect here. Granted, I still prefer Heath Ledger's funnier, more anarchic, better-acted take on the role, but Nicholson's Joker, unlike previous live-action iterations simply a ruthless mass murderer, is very good.

That brings us to the film's darkness, infamous in 1989. Again, The Dark Knight has one-upped Batman's on-screen nastiness but not, I think, the earlier film's attitude. Whatever you may say about Christopher Nolan's films - cold procedurals all of them - he tends to choose scripts that ultimate believe in and reward goodness and humanity (as The Dark Knight does repeatedly in its last half-hour). Not so in Batman: here we have a hero who kills off henchmen like there's no tomorrow and, in the film's climax, defeats his opponent with a highly questionable move. If The Dark Knight is willing to show a great deal more darkness, Batman ultimately has a more pessimistic view of the world.

The casting of Keaton, a well-known comedian, was greeted with scepticism, but he is a revelation in the role. Christian Bale is a closer fit to the character's physical description in the comic books, but his Bruce Wayne is nothing but a mask, ultimately shallow, while Batman is his real personality. That works, sure, but Keaton's Wayne - a shy, ordinary man in a mansion he barely knows - is much easier to empathise with. We'd never suspect this nice guy of being Batman, so when he picks up a poker, screaming 'You wanna get nuts? Come on! Let's get nuts!' at the Joker it really works. Keaton's Batman cares about people, whereas Bale's Batman often seems to be quite ready to burn down half of Gotham to get at the Joker. (No-one would do that to Burton's Gotham: a Gothic excess of spires and gargoyles where the Nolan films offer the atmosphere of a techno-thriller, it's just too gorgeous to destroy.)

Despite everything, though, it's not a great film. The plot is functional at best, Basinger is phoning it in, and the action scenes are not quite top-notch. If I like Batman, it's as a radically different vision to the Miller-Nolan school of Batman as man become symbol, brutally disregarding the limitations of his body: in the Millerverse, if Batman's chest had been a mortar, he'd burst his hot heart's shell upon it. Keaton's Batman is defiantly human, struggling with relationships and self-doubt, and he's all the stronger for it.

*With the benefit of hindsight, Moore easily emerges as the greater of the two, but the jury is still out, I think, on who had the greater cultural impact.

Friday, 16 September 2011

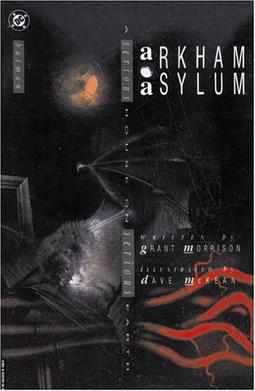

Gotham in ink

Note: This is an updated version of an article originally written in 2008, hence the outdated references.

Wednesday, 5 May 2010

Getting rusty

Here’s a paradox: Iron Man 2 undoubtedly features some good action, some funny moments, and solid performances. In fact, it’s a pretty enjoyable time at the cinema. But it still registers as a distinct disappointment, and I can’t bring myself to love it.

Iron Man 2 starts where the first film, 2008’s critical and box-office darling Iron Man, ended: Tony Stark (Robert Downey jr., as if you didn’t know) has just revealed to the world that he is the man in the metal suit. In Russia, a man called Ivan Vanko (Mickey Rourke) watches the show and swears revenge for his dead father, Anton Vanko, who helped Stark’s father Howard develop the technology now powering Iron Man’s armour. He may look like the world’s angriest homeless man, but Vanko is in fact a scientific genius who before long builds his own suit to become the villainous Whiplash, in alliance with Stark’s jealous rival Justin Hammer (Sam Rockwell, back from 2009’s much-praised but little-seen Moon). Meanwhile, Tony Stark makes his aide/nanny Pepper Potts (Gwyneth Paltrow) CEO of Stark Industries, aided by Natalie Rushman (Scarlett Johansson). But the technology keeping Stark alive is also killing him and Stark, faced with his mortality, is beginning to act irresponsible.

I’d like to start out positive. Therefore, two words (one word?): War Machine. Yeah, like that’s a spoiler. Colonel James Rhodes (Don Cheadle, replacing Terrence Howard, who was apparently both greedy and ill-suited for the part) finally gets his own suit of power armour. I could praise Cheadle’s performance, which easily bests Howard’s – but that’s not what I paid to see. What I did pay to see: a heavy suit of metallic grey (no ‘hot rod red’ for War Machine) armed with dual submachine guns, energy repulsors, a missile launcher not-so-amusingly nicknamed ‘the ex-wife’, and a mini-gun on its shoulder. (Thanks, Wikipedia.) The War Machine design works exceptionally well not merely because it’s all kinds of cool in itself, but because it is different from Iron Man – where Iron Man is relatively nimble, War Machine is robust, making up in armour and firepower what he lacks in dexterity. This sounds like a great trade-off to me, really.

The other performances (yes, I know I just praised the designs more than Don Cheadle) range from the great to the solid. Sam Rockwell is particularly enjoyable: his Justin Hammer is desperate to impress, smarmy and not a little pathetic – but without ever becoming mere comic relief. By contrast, Scarlett Johansson as Black Widow (replacing Emily Blunt, who had to drop out of the project due to scheduling conflicts) isn’t bad per se, she just has little screen time and feels terribly tacked on. After seeing the movie, undertake the following little exercise: go through the film and ask yourself which part of the plot wouldn’t have worked without her presence. Alas, the filmmakers forgot Mark Twain’s rule that ‘the personages in a tale, both dead and alive, shall exhibit a sufficient excuse for being there’. (Miss Johansson’s looks do not constitute a ‘sufficient excuse’, but I’ve never found her all that attractive, so I may be biased.)

Black Widow is part of a larger problem: Iron Man 2 is not merely the second instalment in a franchise, but an introduction into the unfolding Marvel film universe. So a section in the middle of the film is given over to Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson with an eye-patch – you may think this is automatically awesome, but zounds, you’d be wrong) narrating exposition about S.H.I.E.L.D. and all kinds of things that will be quite central when The Avengers comes out barely two winters hence, but not now. When it’s not spinning its wheels, Iron Man 2 recycles material from its predecessor. For this reason large parts of the film are, who thought I’d say this, boring, and you’d never guess it’s actually a little shorter than its predecessor, for it certainly feels a good half-hour longer. Where Iron Man was a taut, fun thrill-ride, the sequel is undeniably flabby.

In the process, much of what made Iron Man such a delight is sacrificed. Being a superhero sequel in the twenty-first century, the second film must of course be serious and dour (but must it also be dramatically inert?): Tony Stark’s former cheerful devil-may-care attitude is therefore replaced with grim foreboding. The delight of his banter with Pepper Potts, arguably the foundation of Iron Man’s success, is thus greatly reduced. Pepper, in fact, is barely in this film, and she’s far less fun, which is the writer’s fault, not Gwyneth Paltrow’s. As for Downey, he’s still exuding charisma, but I’m tiring of him. The humour mostly falls flat in this instalment, too. (The exception: there's a surprise cameo by Bill O'Reilly that I rather enjoyed.) Much of this is a case of diminishing returns; but one cannot but blame Justin Theroux’s script, which is in pretty much every way inferior to Iron Man’s, churned out by a larger team of writers.

If the script is sadly sub-par, Iron Man 2 also showcases Jon Favreau’s weaknesses as a director. In an early scene of Stark signing autographs, Favreau uses nonsensical POV shots. Later in the film, there is a brawl scene that is filmed poorly and edited worse, so that it utterly fails to register. Both script and direction deficiencies come together in a tremendously ill-judged party scene that should not have been written and, being written, should not have been filmed that way. It’s neither funny nor pathetic (in the Greek sense of the word), and it’s a microcosm of Iron Man 2’s inferiority to its predecessor. On the other hand, Favreau shows that he still knows how to make big hunks of metal punching each other interesting, which immediately makes him a better director than Michael Bay. And given that that’s what audiences will be there to see, no-one could claim Favreau doesn’t deliver.

Iron Man 2 is not as good as its predecessor. But neither is it a disaster. It does all the things Iron Man did, and all of them a little worse. Parts of it are dour and inert; others are a lot of fun. Bottom line: it’s just… okay. You won’t be angry you spent money on it, and in today’s world of summer blockbusters, that’s something to be grateful for.