The story behind Peter Watkins's 1965 docu-drama The War Game is gnarled and contentious. Funded by £10,000 from a reluctant BBC at a time of power struggle inside the Corporation, the final 48-minute film made higher-ups profoundly uncomfortable. After privately screening The War Game for representatives of several government departments (including the Ministry of Defence, the Home Office and the Post Office), the BBC decided not to broadcast the film.*

The resulting imbroglio is detailed in Watkins's account, which makes fascinating reading for anyone interested in the raison d'état of the rump British Empire in the sixties. The BBC tried to shake off accusations of political censorship by screening the film to select elite audiences - specifically excluding film critics -, but scrupulously avoided showing it to a wider public. As Watkins stresses, the print media overwhelmingly backed the BBC's line (some choice quotes there).

The film's rehabilitation began when a limited theatrical run resulted in The War Game winning Best Documentary Feature during the 1966 Academy Awards. The BBC, which had previously claimed that it was only Watkins's artistic failings that had led them to suppress the film - as we all know, the Corporation cares deeply about our delicate artistic sensibilities, which is why Top Gear exists - finally broadcast The War Game in 1985, as part of the forty-year anniversary coverage of the bombing of Hiroshima. For his part, Watkins has continued as a stridently left-wing and anti-war documentary filmmaker, falling foul of censorship as often as he's won awards.

The War Game falls into three kinds of footage, mixed within the film. First, there are short interviews with a random sample of passers-by ('Do you know what Strontium-90 is, and what it does?') which reveal the British public as woefully underinformed on the horrors of nuclear war. Interspersed, there are monologues based on real recorded statements by authority figures in government, military and church, which tend towards the utterly insane presented with a certain cheer ('The Aztecs on their feast days would sacrifice 20,000 men to their gods in the belief that this would keep the universe on its proper course. We feel superior to them.')

The meat of the film and the source of most controversy, though, is a merciless recreation of the horrors of a Soviet nuclear strike on Kent, presented in the style of a documentary. A Chinese ground invasion of South Vietnam leads to the US authorising the use of tactical nuclear weapons - first in Indochina, then, as tensions escalate between the blocs, in Germany. This is followed by Soviet massive retaliation on targets in western Europe, including the UK. Apart from the millions killed instantaneously, much of British society collapses in the following months as radiation disease, starvation and post-traumatic stress overwhelm a totally inadequate civil defence system.

Filming around Tonsbridge, Gravesend, Chatham and Dover, Watkins uses almost entirely non-professional actors (ironically considering the director's left-wing stance, this caused him some trouble with actors' unions). He achieves a sense of extraordinary immediacy by using a lot of shaky handheld camerawork (old hat in 2012, revolutionary then), realistically imperfect dialogue, and seemingly unscripted moments. Among a talented crew, Lilian Munro's make-up work stands out for its unflinching recreation of injuries (severe burns, poisoning), skin covered in soot, and other misery.

All of which sounds a bit technical, so let me be clear, in the manner of the Prime Minister: The War Game is among the most horrifying films I've ever seen. I don't say that lightly or frivolously. In the many, many hours I've misspent watching exploitation films, only The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Cannibal Holocaust have sickened me to my very soul to the same extent as The War Game. That's not because it's particularly explicit (much of the film works by suggestion), but because what is portrayed is just so much more gut-churningly awful than what even the most depraved horror directors tend to dream up: newly blind children covering their faces after the brightness of a thousand suns has burnt their retinas, people dying from carbon monoxide poisoning, others beaten to death by starving mobs.

In all that, Watkins is keen to stress that what he's portraying is not speculative but merely a dramatisation of existing scientific predictions. 'It's been estimated that...', begins sentence after sentence of horrifying statistics that imbue the film with a sense of inexorability. Reviewers were of course right to call The War Game totally one-sided: but who could imagine a 'balanced' film on this subject? A documentary that detailed the horrors of atomic fallout before enumerating the many wonderful upsides of nuclear weapons would surely be more repulsive than The War Game, not less.

There is, then, a disgusting hypocrisy in the official response to The War Game. According to the defence and media establishment, planning the murder of millions upon millions of civilians is quite all right just so long as one uses the correct euphemisms; the moral transgression apparently lies in spelling out the reality. As Orwell said, the genocidal reality of modern power 'can indeed be defended,

but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which

do not square with the professed aims of the political parties'. Hence the need for obfuscating language and misinformation - which, as Watkins points out, is precisely likely to increase casualties in the eventuality of war.

A mere calm listing of the inevitable horrors of all-out atomic war would refute any case for nuclear weapons, but that's not all Watkins does. By focusing on the darker aspects of Allied conduct in the Second World War, he critiques the justifying ideologies of British power. Again and again, the narrator stresses that the scenario is merely an extrapolation of what happened to Hamburg, Darmstadt, Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: and who dropped those bombs? When the firestorm created by a one-megaton bomb destroys Rochester, 'the oxygen is being consumed in every cellar and every ground floor room'. Which is how 42,000 civilians died during Operation Gomorrah, after Bomber Command developed the proper scientific combination of incendiary and explosive bombs to create a firestorm. After the initial Soviet attack, Watkins describes British bombers on their way to retaliation. 'Their target: people like this.'

It's really no surprise, then, that The War Game was thought excessively subversive, and its suppression on explicitly political grounds defended in the press. '[T]he only possible effect of showing it to the British public at large would be ... to raise more unilateral disarmament recruits', the Evening News insisted.** The entirely correct accusation against Watkins was thus one succinctly expressed in the hideous German word Wehrkraftzersetzung, literally 'sapping of defensive strength': the danger of showing the film would be to incline the British people against any possibility of a war they'd been systematically misinformed about.

All of which might be interesting historically, but unfortunately the BBC is still at it. Acting as the mouthpiece of the government in the run-up to the conquest of Iraq, refusing to broadcast humanitarian appeals when the aggressor happens to be a is a British ally, shutting down commentators who wouldn't fall in line during the riots: more than ever, the BBC has a reputation for being regime media - structurally, not just incidentally. All the more reason to hold up The War Game as the little docu-drama all the Corporation's horses and all the Corporation's men couldn't bury.

*The BBC officially denies this screening ever happened.

**According to Watkins's website.

Showing posts with label war. Show all posts

Showing posts with label war. Show all posts

Wednesday, 16 January 2013

Sunday, 13 January 2013

Surviving empire's wars

|

| Poster at coproductionoffice.eu. |

Conceived by Rossellini with co-writers Federico Fellini and Sergio Amidei during the months of occupation in 1944, Rome, Open City is a feature-length amalgamation of what was originally to be two documentaries: one on Roman children sabotaging the German forces, another on a Catholic priest executed for aiding the resistance. The seams definitely show: it is, indeed, a bit of a rickety creation, plagued by uncertain financing and the lack of decent working studios, processing facilities or, well, anything.

Against the odds, though, Rome, Open City emerged as a work of genius, and the first great success of Italian neo-realism: though 'success' means foreign critics, really, as Italian audiences were not particularly receptive to a recreation of horrors they had experienced barely a year previously. Which I get: if you're struggling every day to find enough food and fuel to keep you going, a film that opens and ends on a tracking shot of your wartorn capital probably won't be your idea of escapist entertainment.

In the winter of 1943-44, resistance officer Giorgio Manfredi (Marcello Pagliero) narrowly escapes capture by the Gestapo and goes to hide out at the flat of his friend Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), a communist engaged to a widow, Pina (Anna Magnani), who is first seen orchestrating the looting of a bakery. Meanwhile the parish priest, Don Pietro Pellegrini (Aldo Fabrizi), works for the resistance by passing messages and money. But the local Gestapo commander, SS Sturmbannführer Bergmann (Harry Feist), is on their trail with the help of his Fascist counterpart, the police president of Rome (Carlo Sindici).

Now, about those seams: the script's looseness is generally a strength, but at times plot holes open. It's certainly the case that a band of Don Pietro's students, led by Pina's son Marcello and his friend Romoletto (I've not been able to ascertain the actors' names, so please do comment if you know them), are in there somewhere committing acts of petty sabotage against the Germans. But Romoletto's outsized heroism is shown as foolish in a scene in which Don Pietro has to take a makeshift bomb from him, and the boys disappear from the film at the half-way mark only to reappear right at the end. It is quite generally a film in which characters seem to appear and drop off the face of the earth with little rhyme or reason: Francesco, too, vanishes at a certain point, after which the focus narrows to Don Pietro, Manfredi, and their Axis pursuers.

What's more, Rome, Open City was shot silent, presumably for lack of sound stages, and sound dubbed in later. This is effective, with the possible exception only of some of the voice acting. Praise where it is due, though: many of the actors dubbing the Germans' lines are clearly native speakers (Joop van Hulzen speaks perfect German, like most Dutchmen seem to), and the German dialogue is generally not only flawless but pleasingly idiomatic (if you can bear the horrid military-inflected jargon the Nazis created, that is). There's one glaring exception, though: for unless Austrian-born Harry Feist grew up in some seriously weird linguistic enclave, his dialogue was overdubbed by a non-native speaker - who, to add insult to injury, was asked to intone minor errors like intransitive 'fortzusetzen' ('fortzufahren' would be correct). Ah, but I'm nitpicking.

Despite being largely a chamber piece, Rome, Open City contains impressive shots: one, of Pina running after a German truck, is rightly famous. Even so, the look of the film is - well, not slapdash, but it certainly looks like several kinds of film stock were used, that being pretty low on everyone's list of priorities at the time. Surprisingly, though, most of the variety in the film's aesthetic (which one imagines caused cinematographer Ubaldo Arata no shortness of headache) is caused not by stock but by inconsistent and difficult post-processing. Suffice it to say that more than once in the course of 102 minutes, it suddenly feels like we've stepped into a different film.

Those open seams might be considered flaws, but their effect is the opposite: they make the film feel fresh, startling and immediate even after decades. And that certainly contributes to the feeling of realism - which should not be misunderstood: much of Rome, Open City is thoroughly melodramatic, full of fiendish stereotypical villains (dancers sleeping with German officers for money and comforts, evil lesbians, camp SS commanders) and pure-hearted heroes (a hard-working widow, a fussy yet selfless priest). But there is as much surprising nuance as there is cliché: the atheist who prefers being married by a priest to having to step in front of Fascist officials, say, or the timid Austrian deserter (Ákos Tolnay).

More importantly, though, the realism of Rome, Open City lies in its unvarnished examination of a people under occupation. Not without humour, of course: I've come to accept that, in the same way every Bollywood film seems to have song-and-dance numbers irrespective of the subject matter, every Italian film of the first three post-war decades will contain silly humour, although what is offered here is grimmer than usual (Bergmann's conversations being disturbed by the screams of tortured men, for example). Realism, I said: Rossellini deals frankly with hunger and ration books, as well as controversial social issues like pregnancy outside wedlock, which British films like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning would not get around to doing for another fifteen years - contemporary social dramas like The Stars Look Down (1940) still have considerably stuffier morals.

More importantly, though, the realism of Rome, Open City lies in its unvarnished examination of a people under occupation. Not without humour, of course: I've come to accept that, in the same way every Bollywood film seems to have song-and-dance numbers irrespective of the subject matter, every Italian film of the first three post-war decades will contain silly humour, although what is offered here is grimmer than usual (Bergmann's conversations being disturbed by the screams of tortured men, for example). Realism, I said: Rossellini deals frankly with hunger and ration books, as well as controversial social issues like pregnancy outside wedlock, which British films like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning would not get around to doing for another fifteen years - contemporary social dramas like The Stars Look Down (1940) still have considerably stuffier morals.Above all, though, the film tastes of fear: fear of speaking over the phone lest the secret police listen in, fear of being caught outside after curfew. And, everpresent, fear of being dragged out and roughly handled when the occupier chooses to raid your house. I'd say I don't want to preach at y'all, but that's precisely what I'm going to do: the picture Rossellini paints of life under foreign occupation is startlingly similar to the war in Iraq, complete with civilians murdered during house raids. The German regime in Italy is portrayed not so much as fascist as simply technocratic: it serves no end except to perpetuate itself. And barely even that: for as Bergmann cheerfully acknowledges, the Nazis will have to withdraw from Rome sooner or later.

Not that, in foregrounding counter-insurgency, Rossellini neglects the role Italian Fascist collaborators play in enabling Nazi rule. Indeed, the film appears downright prescient when Bergmann prophesies trouble after an Allied victory: for considering the 1948 election, the Years of Lead and Operation Gladio, what European country besides Greece had such a fractious, violent postwar history as Italy? When challenged as to why he's working with atheists, Don Pietro says: 'I believe that anyone who fights for justice and freedom walks in the ways of the Lord.' For a film so invested in the grubby details of ordinary life, Rome, Open City relies on religious imagery to an extraordinary degree. Unless, perhaps, the greatest sacred value lies in thoroughly earthly acts of earthly kindness. That is at the heart of Don Pietro's character - and at the centre of the film.

Saturday, 31 December 2011

Class and class struggle in early Rome

Despite its grandiose title, this post - long delayed by being away from my copy of Livy's Ab urbe condita - does not offer an outline of class struggle in the early Roman Republic as a whole. It is intended, instead, to provide a brief introduction to how Livy frames conflict between the orders. (This is based on The Early History of Rome, the Penguin translation of the first five books of Ab urbe condita, which ends with the sack of Rome by the Gauls.)

The early Republic was a Beutegemeinschaft, a society based on capturing and distributing loot through annual warfare. Success in war kept the gold flowing and was thus integral to the survival of the state, which exported its tensions. For this, the patricians - Rome's ancient aristocracy, the political and religious elite - required the consent of the far larger plebeian class, who did most of the fighting.

This was exploited by the plebeians in the first secessio plebis in 494 BC - a general strike in which the plebeians, rather than respond to military summons, left the city, gathered on the Mons Sacer and threatened to found a new town. Grievances included disadvantages in the allocation of land in colonies, armed Roman settlements built to subdue captured enemy territory, and the patricians' exclusive privileges. The patricians made significant concessions, including the institution of plebeian tribunes, representatives of the plebs who could influence the legislative process. The ongoing tug-of-war between the tribunes and the Senate occupies much of Livy's account.

Most of what we learnt in school, though, was about Rome's foreign wars, not her internal struggles. This is hardly surprising, since the conflict of the orders offers none of the dramatic bloodletting of Porsena's siege of Rome or the wars against Veii; but in truth the social conflict, mostly confined to forums and laws though it is, provides thrills aplenty. It also has the advantage of being less overgrown with fictions and the rigid narrative framework all accounts of foreign wars had to follow.

Livy includes a beautiful vignette that encapsulates the patricians' fears at the opening of his fourth book. Faced with the prospect of a bill brought by the plebeians that would legalise intermarriage between the orders - an unthinkable travesty to the aristocracy - the consuls M. Genucius and C. Curtius respond (4.1):

In all communities the qualities or tendencies which carry the highest reward are bound to be most in evidence and to be most industriously cultivated - indeed it is precisely that which produces good statesmen and good soldiers; unhappily here in Rome the greatest rewards come from political upheavals and revolt against the government, which have always, in consequence, won applause from all and sundry. Only recall the aura of majesty which surrounded the Senate in our father's day, and then think what it will be like when we bequeath it to our children! Think how the labouring class will be able to brag of the increase in its power and influence! There can never be an end to this unhappy process so long as the promoters of sedition against the government are honoured in proportion to their success. Do you realise, gentlemen, the appalling consequences of what Canuleius is trying to do? If he succeeds, bent, as he is, upon leaving nothing in its original soundness and purity, he will contaminate the blood of the ancient and noble families and make chaos of the hereditary patrician privilege od 'taking the auspices' to determine, in the public or private interest, what Heaven may will - and with what result? that, when all distinctions are obliterated, no one will know who he is or where he came from! Mixed marriages forsooth! What do they mean but that men and women from all ranks of society will be permitted to start copulating like animals? A child of such intercourse will never know what blood runs in his veins or what form of worship he is entitled to practise; he will be nothing - or six of one and half a dozen of the other, a very monster!We're not supposed to like these consuls (whose speech, of course, is fabricated wholecloth by Livy). The points made, though, are familiar: the belief that rampant disobedience to authority is crippling the commonwealth, as the Tories affirm; the notion that society, politically correct as it is, rewards the lazy and insubordinate; and lastly, a fear of what, in a different day and age, the Americans called miscegenation, which will lead to human beings becoming as beasts. There's nothing more heartening than reading millennia-old rants warning of the imminent collapse of human civilisation - it puts the Daily Heil in perspective.

We might call Livy's stance on all this broadly call patriotic: he firmly disapproves of internal strife that weakens Rome against her enemies. To this end, he demands justice for the plebeians and repeatedly censures the more arrogant of the patricians: but he also wishes the plebeians would cease to cause trouble. That Livy's narrative should be dominated by his desire for internal peace is hardly surprising. He was writing towards the end of the first century BC, when the period of vicious and hugely destructive civil wars - still within living memory - had ended with the dominance of Augustus, who is praised for restoring concord (even as Livy holds modern morals to be depraved).

Even as the plebeians fought for increased rights, they nonetheless had a stake in Roman society. In consequence they should not be reckoned the wretched of the earth but, perhaps, something of a labour aristocracy, set above the landless and the unfree. 'We propose that a man of the people may have the right to be elected to the consulship', argued Canuleius (4.1): 'Is that the same as saying some rogue who was, or is, a slave?'Social stratification eventually lead to the absorption of the richer plebeians into a broader Roman aristocracy, the nobilitas. It wasn't until the Social Wars and the slave risings of the first century BC that the dispossessed again threatened the integrity of Roman class society.

Labels:

antiquity,

conservatism,

empire,

historical materialism,

history,

war

Saturday, 17 December 2011

Wars and rumours of wars

Left Behind: World at War (2005) caused consternation on the 'boards because it took a lot of liberties with the source material. This is tremendously wrong-headed. It is almost universally acknowledged that the Left Behind books are, in fact, extraordinarily awful, and boldly deviating from the written word should thus improve the product to no small extent.

So it turns out: World at War is far and away the best installment in the series. It's not Shakespeare, but it is a fully functional, at times legitimately exciting film - despite or perhaps because of the fact that its nominal heroes do virtually nothing throughout. With TV veteran Craig R. Baxley the series finds a director with actual visual flair for the first time, and in Lou Gossett, Jr. there's a seasoned actor to do some of the heavy lifting Cameron & Co. can't.

The opening scene - set inside a partially destroyed and burning White House - is clichéd and a little stupid, but it works well enough, and in that it's a microcosm of the film. Inside the Oval Office, President Gerald Fitzhugh (Lou Gossett, Jr.) videotapes his confession. There has, apparently, been a massive war, Fitzhugh and the United States have lost, and the president feels responsible. Can I say how nice it is to get a cold open instead of the laborious exposition of the previous films?

A week earlier, at a Global Community compound, a group clad in balaclavas break in and steal a shipment of bibles. Ambushed by GC forces, one of the burglars is captured. He turns out to be Chris (David MacNiven), who was converted in Tribulation Force. When he refuses to renounce Jesus at gunpoint, Chris is executed. We find out it's some time after the events of the last film. Individual nations still exist, but are largely disarmed and overshadowed by the one-world government of Nicolae Carpathia (Gordon Currie). Armed resistance to the Global Community comes mainly from the militia movement; Christianity has been outlawed and driven underground.

The first time we meet the Tribulation Force, they're literally hiding in the basement beneath the ruins of New Hope Village Church, which doesn't seem particularly stealth. Pastor Bruce Barnes (Arnold Pinnock, taking over from Clarence Gilyard) is presiding over a double wedding: Chloe Steele (Janaya Stephens) is marrying Buck Williams (Kirk Cameron), while her father Rayford (Brad Johnson) weds Amanda White (Laura Catalano). Getting married together with your dad may be slightly creepy, but this scene is quite well done and somewhat touching, though cheesy.

The plot mostly turns on President Fitzhugh, though. His vice-president (Charles Martin Smith) has discovered that Carpathia is developing biological weapons, but he's assassinated by unknown gunmen before he can tell Fitzhugh all he knows. The president decides to investigate and, teaming up with Carolyn Miller (Jessica Steen) breaks into Carpathia's biological lab. (Shouldn't he have minions to do this for him?) They discover that Carpathia is infecting bibles with a deadly virus to take out the underground churches. Before long, Christians all over the country are falling ill, including Bruce and Chloe. Meanwhile, the president is liaising with his British (Shaun Astin-Olsen, whose British accent is terrible) and Egyptian (Elias Zarou) colleagues in planning an all-out surprise attack against Carpathia's forces.

As I mentioned earlier, the protagonists don't do much: Rayford and Amanda mostly spend their time fretting, Buck meets the president twice, and Chloe looks after the infected before falling ill herself. Actually moving the plot forward falls on Lou Gossett's capable shoulders. This is to the good although Johnson, Catalano and Stephens also continue to create strong, believable characters. I can't help feeling a little sorry for Gordon Currie, a competent actor looking for an angle on the villainous Carpathia the script just doesn't provide. Similar praise, hower, can't be lavished on Kirk Cameron and Chelsea Noble in the role of Hattie Durham: Mr and Mrs Kirk Cameron, the only True Believers in postmillennial dispensationalism among the cast, are far and away the worst actors, and I can't help feeling these two facts must somehow be related.

In contrast to previous installments' obsession with racing through the end times checklist, World at War's script benefits greatly from its interest in what it might be like to live in the earth's last days, and how Christians mightr persevere under Antichrist's persecution: That gives the film an emotional heft its lesser brethren simply cannot muster.

Of course, there's a great deal of wish fulfilment in there: the underground churches' activities allow the audience to feel like bad-ass guerrillas for the Lord. Like previous installments, World at War's plot suffers by running headlong into problems of divine sovereignty versus human free will: if the Antichrist's reign has been foretold, what point is there in fighting him? (The film also engages in a baffling Zwinglian polemic by insisting that communion wine 'is to remind you of the precious blood Christ shed for you' [emphasis mine] and is not, say, the blood of the covenant.)

What really elevates World at War above its predecessors, however, is the direction. In the hands of Craig Baxley, the film finally shows rather than tells: that initial shot of the ruined New Hope Village Church is shocking and communicates in one image what a film ago would have been established by ponderous dialogue. Although Baxley uses too many close-ups for comfort, his visual language is generally uncluttered, efficient and exciting. Further praise goes to the production design: with a limited budget, Rupert Lazarus creates tremendously satisfying sets, especially of Carpathia's headquarters, which are just the right combination of Lucifer and paranoia techno-thriller. The awkwardly inserted Christian songs are gone, too, praise Jesus.

World at War is superior to its predecessors in every way: wherefore, of course, it sank the franchise and destroyed any notion of another sequel. Six years on, though, it seems a reboot/remake is on the way. One can only hope Cloud Ten Pictures will scorn the tedium of the books and take their inspiration from the dark, effective and bold third film, faithfulness to the source material be damned.

In this series: Left Behind: The Movie (2000) | Left Behind II: Tribulation Force (2002) | Left Behind: World at War (2005)

So it turns out: World at War is far and away the best installment in the series. It's not Shakespeare, but it is a fully functional, at times legitimately exciting film - despite or perhaps because of the fact that its nominal heroes do virtually nothing throughout. With TV veteran Craig R. Baxley the series finds a director with actual visual flair for the first time, and in Lou Gossett, Jr. there's a seasoned actor to do some of the heavy lifting Cameron & Co. can't.

The opening scene - set inside a partially destroyed and burning White House - is clichéd and a little stupid, but it works well enough, and in that it's a microcosm of the film. Inside the Oval Office, President Gerald Fitzhugh (Lou Gossett, Jr.) videotapes his confession. There has, apparently, been a massive war, Fitzhugh and the United States have lost, and the president feels responsible. Can I say how nice it is to get a cold open instead of the laborious exposition of the previous films?

A week earlier, at a Global Community compound, a group clad in balaclavas break in and steal a shipment of bibles. Ambushed by GC forces, one of the burglars is captured. He turns out to be Chris (David MacNiven), who was converted in Tribulation Force. When he refuses to renounce Jesus at gunpoint, Chris is executed. We find out it's some time after the events of the last film. Individual nations still exist, but are largely disarmed and overshadowed by the one-world government of Nicolae Carpathia (Gordon Currie). Armed resistance to the Global Community comes mainly from the militia movement; Christianity has been outlawed and driven underground.

The first time we meet the Tribulation Force, they're literally hiding in the basement beneath the ruins of New Hope Village Church, which doesn't seem particularly stealth. Pastor Bruce Barnes (Arnold Pinnock, taking over from Clarence Gilyard) is presiding over a double wedding: Chloe Steele (Janaya Stephens) is marrying Buck Williams (Kirk Cameron), while her father Rayford (Brad Johnson) weds Amanda White (Laura Catalano). Getting married together with your dad may be slightly creepy, but this scene is quite well done and somewhat touching, though cheesy.

The plot mostly turns on President Fitzhugh, though. His vice-president (Charles Martin Smith) has discovered that Carpathia is developing biological weapons, but he's assassinated by unknown gunmen before he can tell Fitzhugh all he knows. The president decides to investigate and, teaming up with Carolyn Miller (Jessica Steen) breaks into Carpathia's biological lab. (Shouldn't he have minions to do this for him?) They discover that Carpathia is infecting bibles with a deadly virus to take out the underground churches. Before long, Christians all over the country are falling ill, including Bruce and Chloe. Meanwhile, the president is liaising with his British (Shaun Astin-Olsen, whose British accent is terrible) and Egyptian (Elias Zarou) colleagues in planning an all-out surprise attack against Carpathia's forces.

As I mentioned earlier, the protagonists don't do much: Rayford and Amanda mostly spend their time fretting, Buck meets the president twice, and Chloe looks after the infected before falling ill herself. Actually moving the plot forward falls on Lou Gossett's capable shoulders. This is to the good although Johnson, Catalano and Stephens also continue to create strong, believable characters. I can't help feeling a little sorry for Gordon Currie, a competent actor looking for an angle on the villainous Carpathia the script just doesn't provide. Similar praise, hower, can't be lavished on Kirk Cameron and Chelsea Noble in the role of Hattie Durham: Mr and Mrs Kirk Cameron, the only True Believers in postmillennial dispensationalism among the cast, are far and away the worst actors, and I can't help feeling these two facts must somehow be related.

In contrast to previous installments' obsession with racing through the end times checklist, World at War's script benefits greatly from its interest in what it might be like to live in the earth's last days, and how Christians mightr persevere under Antichrist's persecution: That gives the film an emotional heft its lesser brethren simply cannot muster.

Of course, there's a great deal of wish fulfilment in there: the underground churches' activities allow the audience to feel like bad-ass guerrillas for the Lord. Like previous installments, World at War's plot suffers by running headlong into problems of divine sovereignty versus human free will: if the Antichrist's reign has been foretold, what point is there in fighting him? (The film also engages in a baffling Zwinglian polemic by insisting that communion wine 'is to remind you of the precious blood Christ shed for you' [emphasis mine] and is not, say, the blood of the covenant.)

What really elevates World at War above its predecessors, however, is the direction. In the hands of Craig Baxley, the film finally shows rather than tells: that initial shot of the ruined New Hope Village Church is shocking and communicates in one image what a film ago would have been established by ponderous dialogue. Although Baxley uses too many close-ups for comfort, his visual language is generally uncluttered, efficient and exciting. Further praise goes to the production design: with a limited budget, Rupert Lazarus creates tremendously satisfying sets, especially of Carpathia's headquarters, which are just the right combination of Lucifer and paranoia techno-thriller. The awkwardly inserted Christian songs are gone, too, praise Jesus.

World at War is superior to its predecessors in every way: wherefore, of course, it sank the franchise and destroyed any notion of another sequel. Six years on, though, it seems a reboot/remake is on the way. One can only hope Cloud Ten Pictures will scorn the tedium of the books and take their inspiration from the dark, effective and bold third film, faithfulness to the source material be damned.

In this series: Left Behind: The Movie (2000) | Left Behind II: Tribulation Force (2002) | Left Behind: World at War (2005)

Labels:

Christianity,

direct to video,

end times mania,

war

Thursday, 27 October 2011

In praise of the Red Army

This post touches on a couple of issues regarding the Eastern Front (1941-45) that have irritated me recently. There's a popular perception of the German-Soviet War, refuted in numerous academic works, that runs roughly like this:

(1) Soviet forces overwhelmed the Wehrmacht by sheer numerical superiority: essentially, a four-year zerg rush.

(2) Hitler caused a great number of German setbacks by procrastination, recklessness, and stubbornness (e.g. a fixation on Stalingrad, the failure to cross the Neva in 1941, etc.)

(3) The Western Allies decided the outcome of the war when they invaded Normandy.

In Germany (3) is uncommon thanks to a general awareness that the Eastern Front consumed the vast majority of the war effort. (All my grandparents lost siblings in the Soviet Union; my grandfather fought as part of Army Group North from 1942 to 1945 and was a Russian POW until 1949.) (1) and (2), however, are widespread beliefs.

It's not difficult to see why. When German generals wrote their memoirs in the fifties, they were eager to exculpate themselves from responsibility for total defeat. Instead they blamed Hitler, who was unlikely to find vigorous defenders, and conveniently dead sycophants like Keitel. Of course Hitler was a bad commander-in-chief, terrible both at military judgment and at managing personal relationships with his generals; but in truth a number of people in the OKW would have found themselves with egg on their faces - like Franz Halder, who confidently noted that '[i]t's not too much to say that the campaign against Russia has been won within fourteen days' in July 1941. Collectively, the German generals easily displayed as much arrogance and short-sightedness as the Austrian corporal.

The Soviets, as pictured in German and Anglo-Saxon popular perception, were inferior to the Wehrmacht in everything but numbers. This sort of claim is at least partly a hangover from Nazi war propaganda: what was the Soviet Union but Asia's endless hordes threatening to overwhelm Western civilisation (the line adopted by the Nazis when they attempted to transform an opportunistic war of conquest into a pan-European crusade against 'Bolshevism' in 1942-43)? A few men, hopelessly outnumbered but superior in virtue, natural nobility, as well as technological and operational genius, fighting to the last against slavering barbarians - why, it's exactly the sort of romantic Thermopylae tripe the Nazis loved until the very end (see Kolberg).

In this racist fantasy the Soviets of course had to appear as the direct opposite of the noble Aryan: countless faceless goons (even though, as in the Battle of Kursk, numbers and losses were much more even than is commonly supposed), incapable of anything but mass charges (despite brilliantly executed operations like Operation Uranus and strategic offensives like Operation Bagration), indifferent to losses (there's some truth to this one, owing to the extraordinary situation of the Red Army in 1941-42, but from 1943 the Soviets were much more careful with their manpower), barbaric in their treatment of civilians (ignoring, like all empires, the systematic atrocities the 'civilised' troops committed against the populace).

It goes without saying that the Red Army was the decisive force in the war. Nazi Germany did not fall because it ran out of oil, and certainly not because of the Allied carpet bombing of German civilians: it perished because 80% of its armed forces were engaged and destroyed by the Red Army, and its conquered territories were occupied by the Soviets. In this the USSR was of course helped by supplies provided by the Western Allies; but it was Stavka that in extraordinarily difficult circumstances planned, and millions of Soviet soldiers that executed, the campaigns that brought European fascism to its knees.

In the First World War, Germany defeated the Russian Empire committing only a third of her forces. It's not to excuse Stalinism to note that Uncle Joe's assessment of the need to catch up in industrial development was spot on. By the 1940s the Soviet Union had become an industrial powerhouse. Soviet equipment was often of equal quality (the notorious German realisation, early in the war, that their tanks were inferior to the T-34 was not an isolated incident), but the Nazis' disastrous decision to focus on quality over quantity squandered what technological edge they did have, massively exacerbating the industrial disparity - another instance of Nazi racism digging its own grave.

It's true that in the early phase of the war - roughly, from June 1941 to the second half of 1942 - the Red Army did not have the strategic initiative and, faced with rapidly advancing German armies, indeed attempted to stop the Wehrmacht by resorting to human waves and other desperate tactics. The result, despite intermittent success, is well known: losses so devastating similar tactics could not be contemplated due to manpower depletion alone from 1943 onwards (although Zhukov did some 1941 re-enactment in the 1945 Seelow Heights and Berlin campaigns).

Instead, having recovered from the initial shock, the Soviets relearnt the doctrine of deep battle their theorists had developed in the 1920s and 1930s. Deep battle, superficially similar to 'Blitzkrieg', is designed to break through to an enemy force's rear and occupy its territory. Unlike the Germans' unhealthy obsession with encircling and annihilating enemy forces (a fascination which, while going back to Clausewitz, was certainly favoured by Nazism's prejudices), the Soviet doctrine envisaged not physically destroying an enemy but confusing him, throwing him off-guard, and breaking his ability and will to act at an operational and strategic level.

Early attempts to put deep battle into practice were not unqualified successes, but from Stalingrad onwards the Soviets perfected the strategy, revolutionising the Red Army at every level. It was most impressively displayed in Operation Bagration, launched two weeks after D-Day. The offensive destroyed far more German forces than the Battle of Normandy, brought the Red Army to the borders of the Reich and, most importantly, shattered Army Group Centre and left the Wehrmacht in shambles. Before Bagration, German forces on the Eastern Front had been well-organised; afterwards, the Wehrmacht never achieved the same coherence and was soon forced to throw together Kampfgruppen, improvised formations of whatever was at hand in a sector.

In short, Soviet forces defeated the Wehrmacht because, from late 1942 onwards, they were the better army. Of course numerical superiority, present in most situations, helped, and so did the Soviet Union's greater industrial output. But all this would have counted for nothing had the Soviets not gained the skill necessary to disorganise and defeat the Wehrmacht at a strategic, operational and, yes, tactical level. The stereotype of an ignorant mass driven to the slaughter by callous commissars does a disservice to the bravery, motivation and skill of Soviet soldiers.

(1) Soviet forces overwhelmed the Wehrmacht by sheer numerical superiority: essentially, a four-year zerg rush.

(2) Hitler caused a great number of German setbacks by procrastination, recklessness, and stubbornness (e.g. a fixation on Stalingrad, the failure to cross the Neva in 1941, etc.)

(3) The Western Allies decided the outcome of the war when they invaded Normandy.

In Germany (3) is uncommon thanks to a general awareness that the Eastern Front consumed the vast majority of the war effort. (All my grandparents lost siblings in the Soviet Union; my grandfather fought as part of Army Group North from 1942 to 1945 and was a Russian POW until 1949.) (1) and (2), however, are widespread beliefs.

It's not difficult to see why. When German generals wrote their memoirs in the fifties, they were eager to exculpate themselves from responsibility for total defeat. Instead they blamed Hitler, who was unlikely to find vigorous defenders, and conveniently dead sycophants like Keitel. Of course Hitler was a bad commander-in-chief, terrible both at military judgment and at managing personal relationships with his generals; but in truth a number of people in the OKW would have found themselves with egg on their faces - like Franz Halder, who confidently noted that '[i]t's not too much to say that the campaign against Russia has been won within fourteen days' in July 1941. Collectively, the German generals easily displayed as much arrogance and short-sightedness as the Austrian corporal.

The Soviets, as pictured in German and Anglo-Saxon popular perception, were inferior to the Wehrmacht in everything but numbers. This sort of claim is at least partly a hangover from Nazi war propaganda: what was the Soviet Union but Asia's endless hordes threatening to overwhelm Western civilisation (the line adopted by the Nazis when they attempted to transform an opportunistic war of conquest into a pan-European crusade against 'Bolshevism' in 1942-43)? A few men, hopelessly outnumbered but superior in virtue, natural nobility, as well as technological and operational genius, fighting to the last against slavering barbarians - why, it's exactly the sort of romantic Thermopylae tripe the Nazis loved until the very end (see Kolberg).

In this racist fantasy the Soviets of course had to appear as the direct opposite of the noble Aryan: countless faceless goons (even though, as in the Battle of Kursk, numbers and losses were much more even than is commonly supposed), incapable of anything but mass charges (despite brilliantly executed operations like Operation Uranus and strategic offensives like Operation Bagration), indifferent to losses (there's some truth to this one, owing to the extraordinary situation of the Red Army in 1941-42, but from 1943 the Soviets were much more careful with their manpower), barbaric in their treatment of civilians (ignoring, like all empires, the systematic atrocities the 'civilised' troops committed against the populace).

It goes without saying that the Red Army was the decisive force in the war. Nazi Germany did not fall because it ran out of oil, and certainly not because of the Allied carpet bombing of German civilians: it perished because 80% of its armed forces were engaged and destroyed by the Red Army, and its conquered territories were occupied by the Soviets. In this the USSR was of course helped by supplies provided by the Western Allies; but it was Stavka that in extraordinarily difficult circumstances planned, and millions of Soviet soldiers that executed, the campaigns that brought European fascism to its knees.

In the First World War, Germany defeated the Russian Empire committing only a third of her forces. It's not to excuse Stalinism to note that Uncle Joe's assessment of the need to catch up in industrial development was spot on. By the 1940s the Soviet Union had become an industrial powerhouse. Soviet equipment was often of equal quality (the notorious German realisation, early in the war, that their tanks were inferior to the T-34 was not an isolated incident), but the Nazis' disastrous decision to focus on quality over quantity squandered what technological edge they did have, massively exacerbating the industrial disparity - another instance of Nazi racism digging its own grave.

Instead, having recovered from the initial shock, the Soviets relearnt the doctrine of deep battle their theorists had developed in the 1920s and 1930s. Deep battle, superficially similar to 'Blitzkrieg', is designed to break through to an enemy force's rear and occupy its territory. Unlike the Germans' unhealthy obsession with encircling and annihilating enemy forces (a fascination which, while going back to Clausewitz, was certainly favoured by Nazism's prejudices), the Soviet doctrine envisaged not physically destroying an enemy but confusing him, throwing him off-guard, and breaking his ability and will to act at an operational and strategic level.

Early attempts to put deep battle into practice were not unqualified successes, but from Stalingrad onwards the Soviets perfected the strategy, revolutionising the Red Army at every level. It was most impressively displayed in Operation Bagration, launched two weeks after D-Day. The offensive destroyed far more German forces than the Battle of Normandy, brought the Red Army to the borders of the Reich and, most importantly, shattered Army Group Centre and left the Wehrmacht in shambles. Before Bagration, German forces on the Eastern Front had been well-organised; afterwards, the Wehrmacht never achieved the same coherence and was soon forced to throw together Kampfgruppen, improvised formations of whatever was at hand in a sector.

In short, Soviet forces defeated the Wehrmacht because, from late 1942 onwards, they were the better army. Of course numerical superiority, present in most situations, helped, and so did the Soviet Union's greater industrial output. But all this would have counted for nothing had the Soviets not gained the skill necessary to disorganise and defeat the Wehrmacht at a strategic, operational and, yes, tactical level. The stereotype of an ignorant mass driven to the slaughter by callous commissars does a disservice to the bravery, motivation and skill of Soviet soldiers.

Monday, 10 October 2011

Once upon a time in the Middle East

The recent slew of films on Lebanon has focused on the 1982 Israeli invasion of the country: Waltz with Bashir (2008) and Lebanon (2009) both dealt with Israeli soldiers' experience. Incendies (2010) is a high-profile film from a Lebanese perspective, based on a play by Lebanese-Canadian Wajdi Mouawad, that is singularly uninterested in Israel (the 1982 invasion is mentioned in a throwaway comment), presenting instead an odyssey of civil war, family and reconciliation.

Québec, 2009: at the opening of the will, Jeanne Marwan (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and her brother Simon (Maxim Gaudette) discover that their recently deceased mother wants them to pass on letters to their father, whom they believed dead, and their brother, of whose existence they were unaware. Simon, angry at his mother's unusual request, refuses to return to the unspecified Middle Eastern country, but Jeanne decides to find out the truth in a country whose language she doesn't even speak.

This is interwoven with the story of her mother, Nawal Marwan (Lubna Azabal), a Christian from the south of the country, who in around 1970 conducts a love affair with a Muslim refugee. Members of her community kill her lover, but Nawal is already pregnant. She consents, ath the insistence of her grandmother, to give her newborn son to an orphanage and is sent away to university. As the country descends into sectarian strife, she leaves in search of her son but finds the orphanage destroyed. Pretending to be a Muslim for safety, she travels in a group that is eventually massacred by Christian militias. Having escaped only by revealing she is a Christian, Nawal joins a Muslim warlord's forces to wreak vengeance on the killers.

For much of Incendies, I was confused by the film's refuseal to name its setting, for the fictional Middle Eastern country is clearly Lebanon, the place of Wajdi Mouawad's birth. The specific situation of a civil war between Christian and Muslim militias over large numbers of refugees in the south, interrupted by a 'foreign invasion', is not what you'd call vague. By the end I understood. There is a plot twist that is grossly unlikely 'in reality', but brings home the theme of the film:

This twist, an allusion to Greek myth, necessarily throws the film into unreality. Nor, for a film about Lebanon, is Incendies terribly interested in judging that conflict: it is neither pro- nor anti-sectarian, but treats the events of civil war as fate. This attitude is best encapsulated in the retired Muslim warlord Wallat Chamseddine (Mohamed Majd, in a terrific scene-stealing performance), who is neither regretful nor proud of his actions, only wary of the possible consequences. Incendies depicts the civil war as terrible but nonetheless unalterable: its focus is on family shaped by conflict.

All the same, Incendies is a harrowing indictment of inhumanity. A number of scenes dealing with rape as prison torture and its aftermath are very difficult to watch, as is the massacre of a passenger bus by militias, including the shooting of a child. The acting is excellent, especially Lubna Azabal, who portrays Nawal as a person driven by love and, increasingly, revenge for her suffering that leads her to participate in the civil war on the 'other side'. The fluidity of her identity is signalled by a scene in which she quickly hides her cross necklace and puts on a headscarf to approach a group of Muslims.

The writing, adapted from a play, it is perhaps too 'literary': 'L'enfance est un couteau planté dans la gorge' is great writing, but it rings false in the film's setting. (Incidentally, I was pleased to discover my French appears to have gone from abysmal to merely bad, as I was able to understand most of the French dialogue.) The often over-elaborate style points to the film's mythic quality: though rooted in the Lebanese Civil War, it becomes a parable of conflict in the region.

Québec, 2009: at the opening of the will, Jeanne Marwan (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and her brother Simon (Maxim Gaudette) discover that their recently deceased mother wants them to pass on letters to their father, whom they believed dead, and their brother, of whose existence they were unaware. Simon, angry at his mother's unusual request, refuses to return to the unspecified Middle Eastern country, but Jeanne decides to find out the truth in a country whose language she doesn't even speak.

This is interwoven with the story of her mother, Nawal Marwan (Lubna Azabal), a Christian from the south of the country, who in around 1970 conducts a love affair with a Muslim refugee. Members of her community kill her lover, but Nawal is already pregnant. She consents, ath the insistence of her grandmother, to give her newborn son to an orphanage and is sent away to university. As the country descends into sectarian strife, she leaves in search of her son but finds the orphanage destroyed. Pretending to be a Muslim for safety, she travels in a group that is eventually massacred by Christian militias. Having escaped only by revealing she is a Christian, Nawal joins a Muslim warlord's forces to wreak vengeance on the killers.

For much of Incendies, I was confused by the film's refuseal to name its setting, for the fictional Middle Eastern country is clearly Lebanon, the place of Wajdi Mouawad's birth. The specific situation of a civil war between Christian and Muslim militias over large numbers of refugees in the south, interrupted by a 'foreign invasion', is not what you'd call vague. By the end I understood. There is a plot twist that is grossly unlikely 'in reality', but brings home the theme of the film:

Jeanne and Simon's brother (Abdelghafour Elaaziz) is also their father, Nawal's son who, rescued from the destruction of his orphanage by a warlord, became a soldier and, after switching sides, eventually a torturer in the service of the government. In this capacity he raped his mother, rendering her pregnant. Further, he no longer lives in Lebanon, having left the country for Québec after the conclusion of the civil war.

This twist, an allusion to Greek myth, necessarily throws the film into unreality. Nor, for a film about Lebanon, is Incendies terribly interested in judging that conflict: it is neither pro- nor anti-sectarian, but treats the events of civil war as fate. This attitude is best encapsulated in the retired Muslim warlord Wallat Chamseddine (Mohamed Majd, in a terrific scene-stealing performance), who is neither regretful nor proud of his actions, only wary of the possible consequences. Incendies depicts the civil war as terrible but nonetheless unalterable: its focus is on family shaped by conflict.

All the same, Incendies is a harrowing indictment of inhumanity. A number of scenes dealing with rape as prison torture and its aftermath are very difficult to watch, as is the massacre of a passenger bus by militias, including the shooting of a child. The acting is excellent, especially Lubna Azabal, who portrays Nawal as a person driven by love and, increasingly, revenge for her suffering that leads her to participate in the civil war on the 'other side'. The fluidity of her identity is signalled by a scene in which she quickly hides her cross necklace and puts on a headscarf to approach a group of Muslims.

The writing, adapted from a play, it is perhaps too 'literary': 'L'enfance est un couteau planté dans la gorge' is great writing, but it rings false in the film's setting. (Incidentally, I was pleased to discover my French appears to have gone from abysmal to merely bad, as I was able to understand most of the French dialogue.) The often over-elaborate style points to the film's mythic quality: though rooted in the Lebanese Civil War, it becomes a parable of conflict in the region.

Thursday, 25 August 2011

Instant awesome, just add armour (The Great War: Breakthroughs)

Welcome back for the final round of alternate-history Great War mayhem! I complained at length that Walk in Hell, the previous volume in the series, spent six hundred pages spinning its wheels, but I knew the pay-off was rumbling over the hill, blowing smoke and soot, blazing away with cannon and machine guns. Oh yes, it's barrel time!

'Barrels', indeed: for Turtledove had the ingenious idea of renaming those steely beasts of battle, although the British term, 'tanks', is also sometimes used. They turn out to be crucial in deciding the outcome of the war, and boy, do I like how Turtledove goes about this. By War Department doctrine, the US deploy barrels evenly spaced along the front. General Custer, commander of First Army in Tennessee, defies this not out of great strategic insight, but because of his oft-proved incompetence.

Custer, you see, has been well established as your standard 'attack, attack, attack' commander since How Few Remain. In previous books, First Army has suffered terrible losses thanks to his pigheaded offensives against entrenched enemy positions. Now, however, Custer seizes on the unorthodox ideas of Colonel Irving Morrell (a character I like, with a name allusion I can't stand), who wants to deploy barrels en masse and drive armoured spearheads through enemy lines. Presented with the opportunity to wield a really large sledgehammer against the Confederacy, Custer assents, First Army breaks through, and the Confederate defence of Nashville is shattered.

The descriptions of armoured warfare are very much the best part of Breakthroughs, giving the volume a dynamism sorely lacking in Turtledove's previous effort. I mean, how awesome are barrels? (Don't answer that. Obviously we should abolish war as soon as possible, &c.) But it's not just in Tennessee that the front is moving again. In the eastern theatre, the Confederates are driven back into Virginia. In the Trans-Mississippi and Canada, too, Entente forces are losing ground rapidly. As the war draws towards a conclusion, the Confederates are attempting to negotiate peace with honour, while Roosevelt is pushing for a harsh diktat.

The characters are stronger, too. In American Front, Gordon McSweeney was part annoying, part offensive to me as a Christian; in Breakthroughs, he is badassery incarnate in one man. He singlehandedly captures and kills dozens of enemy soldiers, destroys a tank with a flamethrower and eventually performs a crazy-awesome feat of valour I dare not spoil. All this while being utterly insane. Flora Hamburger, whose run for Congress was one of the redeeming features of Walk in Hell, is sadly given little to do here.

But let's talk about artillery sergeant Jake Featherston, a man who is coming to the fore as peace approaches. He's quite an unpleasant human being, a mixture of frustration, envy, and murderous hatred; but his scenes are among the highlights of the book. His futile attempts to stem the Yankee sweep into Virginia render him increasingly embittered, and he begins to write a book blaming the political class and the blacks of the Confederacy for defeat. All this is compelling enough: the trouble comes from the fact that it's perfectly obvious from our timeline where his path leads. This parallelism, which Turtledove is too fond of, is a real problem, breaking suspense in advance.

Breakthroughs is a high point for the series; but just like the peace forged between the American nations, it carries within it the seeds of future trouble. By the end of the book, similarities between the future trajectory of the Confederacy and certain European nations are already heavily implied. To me, that goes against the spirit of alternate history: the author should genuinely spin his timeline, not tether it to real history. But for now it's all good; let us bask in the glory of Turtledove's final Great War novel, and let tomorrow worry about itself.

P.S. As I'm moving and probably won't have access to further novels in the near future, I'm putting this series on hiatus for now, but will get back to it as soon as I can.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Walk in Hell

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Sunday, 21 August 2011

The Great War: Walk in Hell (Southern Victory Series, Part Four)

Middle instalments of trilogies are always a tricky business. The first part has all the interesting set-up, the finale boasts all the pay-off: middle instalments mostly develop themes. But there is quite honestly no reason Walk in Hell should be such an awful slog: no reason except, perhaps, that a stalemate must feel like a slog. In which case Harry Turtledove is a genius, deliberately boring his readers, as Bret Easton Ellis does in American Psycho, to make them feel the tedium-cum-horror of the world they inhabit. Somehow, though, I doubt it.

Walk in Hell begins with the black labourers of the Confederacy rising in Red rebellion. Even though Turtledove fails to develop a version of Marxism more suited to the situation of Southern blacks (compare, for example, Lenin's adjustments to orthodox Marxism for Russian conditions), it's still quite a premise. Unfortunately, the author doesn't exploit the idea: the socialist republics fizzle so quickly that there is no chance to explore life in the envisaged new society.

Elsewhere, the fronts are barely moving. The USA are very slowly advancing everywhere, while the war effort takes an ever-greater toll on civilian life throughout 1916. Characters are being developed and in some cases introduced - Paul Mantarakis stops a bullet in Lower California and is replaced as a point-of-view character by Gordon McSweeney, an insane Presbyterian whom I very much look forward to discussing in my review of Breakthroughs.

This deadlocked state of affairs is of course historical, but Turtledove is too obviously inspired by the Western and Italian (in the case of the Canadian Rockies) Fronts of the real-life First World War. Although Turtledove pays lip service to the less than ideal supply situation in the Trans-Mississippi, fronts should move much more rapidly in the Canadian Prairies as well as Arkansas, Sequoyah and Texas, as they did on the Eastern Front in our timeline. But of course, if the author did that, Canada would be cut in half and knocked out of the war too quickly for dramatic purposes: the Rule of Drama may be invoked here.

I'd also like to take the opportunity to complain obnoxiously, as one does, about one of my greatest bugbears when it comes to Turtledove. For, you see, the author's eagerness to write sex scenes is matched only by his total inability to make them in any way sexy. (Using the term 'chamberpot' in your sex scenes - repeatedly! - is not a good idea.) Given that sex is technically unimportant to the plot, one would be grateful for mercy.

But it's not all bad. There are lovely little touches all over the place. For example, there is an extra named Moltke Donovan: his name is (unusually for Turtledove) never commented upon, but is precisely what we might expect in the world the author has created. And we should not be too hard on Walk in Hell for spinning its wheels for six hundred pages: it's build-up for one hell of a final instalment.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Breakthroughs

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Monday, 25 July 2011

Someday this war's gonna end

Sometimes a film surprises you. I expected First Blood (1982) to be a big, dumb action film. I didn't know anything about it before: nothing more, in fact, than the cliché of Rambo in pop culture. Instead, First Blood turns out to be one of the finest thrillers I have ever seen. I expected big, shiny and shallow; I got small and gritty, with surprising depth.

In the winter of 1981, Vietrnam War veteran John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone, who also co-wrote the script) sets out to visit a friend from his unit in the town of Hope, Washington (portrayed by the town of Hope, British Columbia). Finding out his friend has died from the after-effects of Agent Orange exposure, Rambo sets out to leave town, but is harassed and eventually arrested for vagrancy by local sheriff Teasle (Brian Dennehy), who doesn't like Rambo's scruffy appearance.

In custody Rambo is abused both verbally and physically by police officers including Galt (Jack Starrett) and Mitch (a young David Caruso). When ill-treatment leads to flashbacks of torture in Vietnam, Rambo attacks the policemen and escapes into the mountains. He is pursued by Teasle and his posse, but fights them off, injuring several men and inadvertently killing Galt. Teasle calls in the National Guard and begins a large-scale hunt for Rambo in hostile mountain terrain, although he is warned by Rambo's former commander, Colonel Trautman (Richard Crenna), that Rambo may be too experienced in guerrilla warfare to be captured.

It's been said before, but it's worth stating that Stallone is some manner of genius. He can't always be accused of the best judgment: in a career that includes Rocky and First Blood, he also made Over the Top (the armwrestling film!) and the much-maligned Judge Dredd. His attempts to hide his short stature are legendary. But at his peak he had creativity and determination, and it's Stallone the actor that is First Blood's greatest strength. His John Rambo is a man who hides his war and post-war scars beneath a bland exterior, a drifter both literal and metaphorical in an America that appears to have turned its back on him. And Stallone absolutely nails his character's crucial scene, a monologue at the end that is both riveting and harrowing.

Its focus on the treatment of Vietnam War veterans ultimately makes First Blood into political cinema. This was a near-ubiquitous trope in the aftermath of Vietnamese victory: Taxi Driver (1976) and The Deer Hunter (1978) dealt with the mental scars war inflicts, while Bruce Springsteen's 'Born in the USA' (1984) lambasted the United States' failure to reintegrate their veterans into society ('Went to see my VA man / He said, "Son, don't you understand?"').

That an arrest over vagrancy turns into a deadly manhunt is symptomatic of a failure to make peace - not just between Vietnam and the American empire, but also between veterans and society at large (Rambo: 'Nothing is over! Nothing! You just don't turn it off! ... Back there I could fly a gunship, I could drive a tank, I was in charge of million dollar equipment, back here I can't even hold a job parking cars!') Rambo is a man perpetually at war, and - without giving away too much - the ending is perfect in recognising this as the film's central theme.

Next to all the implicit and explicit politics, however, First Blood is also a brilliant action thriller. For starters, at 97 minutes it is absolutely fleet, without an ounce of padding. The action is brilliantly choreographed and shot and surprisingly realistic, particularly in the early and middle part of the film (towards the end it's a different story). And, in another validation of the old rule whereby an action film's quality is inversely proportional to amount of bloodshed shown* there is only one certain death. In 2011 as in 1982, an entertaining but thought-provoking action film that packs a punch like this is a rarity.

*Let's call it Q = k 1/b, where Q = quality, k = a constant I have yet to discover, and b = bodies.

In the winter of 1981, Vietrnam War veteran John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone, who also co-wrote the script) sets out to visit a friend from his unit in the town of Hope, Washington (portrayed by the town of Hope, British Columbia). Finding out his friend has died from the after-effects of Agent Orange exposure, Rambo sets out to leave town, but is harassed and eventually arrested for vagrancy by local sheriff Teasle (Brian Dennehy), who doesn't like Rambo's scruffy appearance.

In custody Rambo is abused both verbally and physically by police officers including Galt (Jack Starrett) and Mitch (a young David Caruso). When ill-treatment leads to flashbacks of torture in Vietnam, Rambo attacks the policemen and escapes into the mountains. He is pursued by Teasle and his posse, but fights them off, injuring several men and inadvertently killing Galt. Teasle calls in the National Guard and begins a large-scale hunt for Rambo in hostile mountain terrain, although he is warned by Rambo's former commander, Colonel Trautman (Richard Crenna), that Rambo may be too experienced in guerrilla warfare to be captured.

It's been said before, but it's worth stating that Stallone is some manner of genius. He can't always be accused of the best judgment: in a career that includes Rocky and First Blood, he also made Over the Top (the armwrestling film!) and the much-maligned Judge Dredd. His attempts to hide his short stature are legendary. But at his peak he had creativity and determination, and it's Stallone the actor that is First Blood's greatest strength. His John Rambo is a man who hides his war and post-war scars beneath a bland exterior, a drifter both literal and metaphorical in an America that appears to have turned its back on him. And Stallone absolutely nails his character's crucial scene, a monologue at the end that is both riveting and harrowing.

Its focus on the treatment of Vietnam War veterans ultimately makes First Blood into political cinema. This was a near-ubiquitous trope in the aftermath of Vietnamese victory: Taxi Driver (1976) and The Deer Hunter (1978) dealt with the mental scars war inflicts, while Bruce Springsteen's 'Born in the USA' (1984) lambasted the United States' failure to reintegrate their veterans into society ('Went to see my VA man / He said, "Son, don't you understand?"').

That an arrest over vagrancy turns into a deadly manhunt is symptomatic of a failure to make peace - not just between Vietnam and the American empire, but also between veterans and society at large (Rambo: 'Nothing is over! Nothing! You just don't turn it off! ... Back there I could fly a gunship, I could drive a tank, I was in charge of million dollar equipment, back here I can't even hold a job parking cars!') Rambo is a man perpetually at war, and - without giving away too much - the ending is perfect in recognising this as the film's central theme.

Next to all the implicit and explicit politics, however, First Blood is also a brilliant action thriller. For starters, at 97 minutes it is absolutely fleet, without an ounce of padding. The action is brilliantly choreographed and shot and surprisingly realistic, particularly in the early and middle part of the film (towards the end it's a different story). And, in another validation of the old rule whereby an action film's quality is inversely proportional to amount of bloodshed shown* there is only one certain death. In 2011 as in 1982, an entertaining but thought-provoking action film that packs a punch like this is a rarity.

*Let's call it Q = k 1/b, where Q = quality, k = a constant I have yet to discover, and b = bodies.

Thursday, 14 July 2011

Love is best

In one year they sent a million fighters forth-Robert Browning, 'Love Among the Ruins'

South and North,

And they built their gods a brazen pillar high

As the sky,

Yet reserved a thousand chariots in full force -

Gold, of course.

Oh heart! oh blood that freezes, blood that burns!

Earth's returns

For whole centuries of folly, noise and sin!

Shut them in,

With their triumphs and their glories and the rest!

Love is best.

Sunday, 10 July 2011

The Great War: American Front (Southern Victory Series, Part Three)

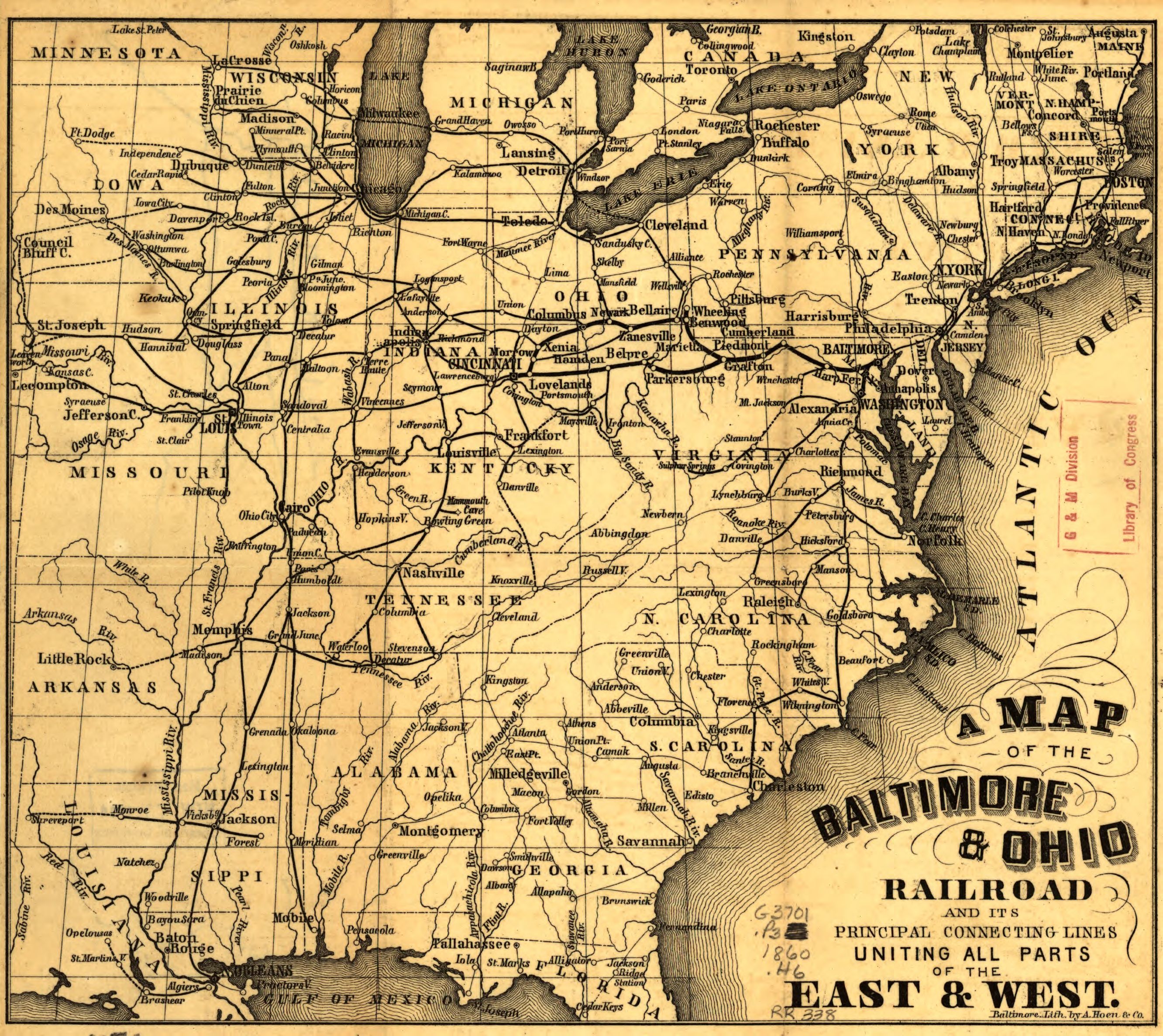

|

| North America in 1914 |

There's a strong argument that the First World War could easily have ended very differently. If the German High Command had not diverted forces eastwards that were later missed during the Battle of the Marne - if Italy or later the United States had remained neutral - if the German spring offensive of 1918 had succeeded... The consequences of Central Powers victory would have been momentous.

So it's no surprise that Turtledove's opening scenario would knock something as precarious in real life as the First World War off balance completely. As you'll remember, in Turtledove's timeline the Confederacy defeats the United States in 1862 and again in 1881 in a rematch over the Confederate purchase of Sonora and Chihuahua from Mexico. Fast forward to 1914, and relations between the two American powers are frosty as ever. The USA, who have maintained close relations with the German Empire since the 1880s, are part of the Central Powers, while the CSA join Britain, France and Russia in the Quadruple Entente. When war breaks out, both powers enter the fray, with the USA having to fight Canada and Britain in the north and the Confederates in the south.

As argued here, this scenario is quite problematic. Conducting an arms race against both Germany and the USA would have overstretched Britain impossibly, and it therefore seems likely Britain would have sought an accommodation with one of these powers. Historically, England decided to remain neutral towards the United States, while planning for a confrontation with Germany; there is no reason why this should be different in Turtledove's timeline.

Indeed, the cost of conducting a land war along a border of almost 4000 miles would have convinced any British policy-makers to maintain neutrality towards the United States at almost any cost. Not to mention that the CSA could provide no benefit to Britain in a European war unless the USA were neutral, freeing up CS resources - an unlikely scenario at best.

I disagree, however, with the notion that Britain would have allied herself with the USA against the CSA. It seems more likely to me that British diplomacy would have been aimed at stopping the war from spreading to North America entirely through neutrality towards the USA, which would have forced the CSA into neutrality, since they could never have fought the North by themselves. Like Britain, Germany would have no incentive to ally itself to the Confederate States.

In Turtledove's timeline, the most likely scenario therefore seems peace in North America, or else an opportunistic US-British alliance in which the US could have attacked the South with impunity. But of course, Turtledove is at this particular point not interested in historical plausibility: what he wants is a massive land war in North America, and his scenario gives it to him.

Like How Few Remain, The Great War: American Front is told through a number of characters. But this time there are rather more of them and they're entirely fictional. That's not without its problems, unfortunately, for Turtledove is on rails here: he feels the need to create allohistorical analogues for people and events that do not occur in his timeline. You get one guess, for example, to figure out who 'Irving Morrell' (say it out loud), US tactician making his name with innovative tactics of surprise and speed on the

Generally the oppressed characters (women, blacks, and civilians living under military occupation) are far more interesting than the relatively tedious middle-class white men. That rule of thumb is not without its exceptions: Anne Colleton, as a Scarlett O'Hara expy, is possibly my least favourite character. The opposite goes for Flora Hamburger (gee, I wonder which real person's name Turtledove might be inspired by here), socialist agitator in New York, who I can really root for.

Unfortunately, American Front is also somewhat less well written than How Few Remain, to put it mildly. I present you with the very first paragraph of the book:

The leaves on the trees were beginning to go from green to red, as if swiped by a painter's brush. A lot of the grass near the banks of the Susquehanna, down by New Cumberland, had been painted red, too, red with blood.Someone please make him stop. Clumsy exposition is another massive problem:

'General McClellan, whatever his virtues, is not a hasty man', Lee observed, smiling at Chilton's derisive use of the grandiloquent nickname the Northern papers had given the commander of the Army of the Potomac. 'Those people' - his own habitual name for the foe - 'were also perhaps ill-advised to accept battle in front of a river with only one bridge offering a line of retreat should their plans miscarry.'This sort of unspeakably awful thing goes on for six hundred pages, I'm sorry to say. Turtledove was perhaps ill-advised to include in-text exposition rather than append some basic information and allow the reader to figure out a lot of facts, rather than constantly attempting to show how much research he's done. A sense of strangeness, rather than thudding exposition at every turn, would surely serve an alternate history novel well.

So, then: Harry Turtledove is a pretty bad writer. But I'm not ashamed to say I'm devouring this series all the same. It's far more plausible than is usually the case with alternate history, it's aware of social and political issues (especially blacks' struggles) to an uncommon extent, and it offers really fascinating breaks from our timeline and occasional wonderful touches (of which more next time). I do hope it picks up a bit, though.

In this series:

Setting the scene

How Few Remain

The Great War: Walk in Hell

The Great War: Breakthroughs

Labels:

alternate history,

American Civil War,

history,

war

Thursday, 7 July 2011

How Few Remain (Southern Victory Series, Part 2)

This post follows my introduction to the general setting of Harry Turtledove's alternate history timeline in which the Confederacy wins the American Civil War in 1862.

In the Anglosphere at least, Southern victory in the American Civil War is one of the most popular historical 'What ifs?', beaten out only by a certain other scenario which Godwin's law won't let me mention. So Turtledove had to choose an original approach if he wanted to make his mark. That he did it twice is to his credit.