Liam Neeson is a force of nature. His transformation from historical dramas and kindly-mentor roles to action stardom is the most stunningly successful Hollywood rebranding of recent years. It's not just Neeson's 6'4'' frame and steely blue eyes that help the makeover click. Rough around the edges in middle age, the Irishman is not your average slick action star: he portrays men who have lost someone. That made the otherwise simple Taken, and it goes a long way to explain the success of The Grey.

John Ottway (Neeson) is a hunter tasked with keeping wolves away from an oil drilling site in the Alaskan wilderness. When the operation winds up, the men (mostly) look forward to returning to civilisation, but their plane crashes in the middle of nowhere leaving most dead, with just half a dozen survivors. When grey wolves attack, they decide to make a run for the treeline. The rest of the film is essentially a long chase in which the men are picked off one by one, fighting back with very limited success.

Remember how in the rebooted Battlestar Galactica, Adama pretends he knows the way to the Promised Land to give the remnant of humanity hope in a hopeless situation? The Grey doesn't even have that. Ottway - whom we first meet about to blow his head off - doesn't know where they are; he's perfectly aware the group is unlikely to survive, and doesn't pretend otherwise. He makes mistakes that get men killed. There is no destination, no safety for the survivors: there's only running and fighting for as long as they possibly can, not going gentle into that good night.

The advertising would have you believe The Grey is mostly Liam Neeson punching wolves, but not so: it's a philosophical film, all about meaning and fate or the lack thereof. As Diaz (Frank Grillo) points out, the fact that several men survived the plane crash only to be killed by wolves does not bode well for any traditional notion of destiny, while a late-film scene in which Ottway screams defiance mixed with pleading at an empty sky suggests that the filmmakers don't believe in an interventionist God. Even so it's more existentialist than nihilistic as the men find new meanings in their interactions and in the fight itself.

The wolves are created using a mixture of real animals (for close-ups), animatronics and CGI. The latter two look rather poor, in all honesty, so we should be grateful the wolves are rarely shown in detail. Their behaviour is in any case more archetypical than realistic, a physical and philosophical foil to the humans rather than 'real' animals. It's a well-acted, well-shot film: nothing in the career of Joe Carnahan would have led you to suspect he had such a taut thriller in him, but there you have it. Mean, lean and ferocious, The Grey may be more depressing than entertaining, but it makes for a good time at the cinema.

Showing posts with label religion. Show all posts

Showing posts with label religion. Show all posts

Tuesday, 6 March 2012

Monday, 10 October 2011

Once upon a time in the Middle East

The recent slew of films on Lebanon has focused on the 1982 Israeli invasion of the country: Waltz with Bashir (2008) and Lebanon (2009) both dealt with Israeli soldiers' experience. Incendies (2010) is a high-profile film from a Lebanese perspective, based on a play by Lebanese-Canadian Wajdi Mouawad, that is singularly uninterested in Israel (the 1982 invasion is mentioned in a throwaway comment), presenting instead an odyssey of civil war, family and reconciliation.

Québec, 2009: at the opening of the will, Jeanne Marwan (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and her brother Simon (Maxim Gaudette) discover that their recently deceased mother wants them to pass on letters to their father, whom they believed dead, and their brother, of whose existence they were unaware. Simon, angry at his mother's unusual request, refuses to return to the unspecified Middle Eastern country, but Jeanne decides to find out the truth in a country whose language she doesn't even speak.

This is interwoven with the story of her mother, Nawal Marwan (Lubna Azabal), a Christian from the south of the country, who in around 1970 conducts a love affair with a Muslim refugee. Members of her community kill her lover, but Nawal is already pregnant. She consents, ath the insistence of her grandmother, to give her newborn son to an orphanage and is sent away to university. As the country descends into sectarian strife, she leaves in search of her son but finds the orphanage destroyed. Pretending to be a Muslim for safety, she travels in a group that is eventually massacred by Christian militias. Having escaped only by revealing she is a Christian, Nawal joins a Muslim warlord's forces to wreak vengeance on the killers.

For much of Incendies, I was confused by the film's refuseal to name its setting, for the fictional Middle Eastern country is clearly Lebanon, the place of Wajdi Mouawad's birth. The specific situation of a civil war between Christian and Muslim militias over large numbers of refugees in the south, interrupted by a 'foreign invasion', is not what you'd call vague. By the end I understood. There is a plot twist that is grossly unlikely 'in reality', but brings home the theme of the film:

This twist, an allusion to Greek myth, necessarily throws the film into unreality. Nor, for a film about Lebanon, is Incendies terribly interested in judging that conflict: it is neither pro- nor anti-sectarian, but treats the events of civil war as fate. This attitude is best encapsulated in the retired Muslim warlord Wallat Chamseddine (Mohamed Majd, in a terrific scene-stealing performance), who is neither regretful nor proud of his actions, only wary of the possible consequences. Incendies depicts the civil war as terrible but nonetheless unalterable: its focus is on family shaped by conflict.

All the same, Incendies is a harrowing indictment of inhumanity. A number of scenes dealing with rape as prison torture and its aftermath are very difficult to watch, as is the massacre of a passenger bus by militias, including the shooting of a child. The acting is excellent, especially Lubna Azabal, who portrays Nawal as a person driven by love and, increasingly, revenge for her suffering that leads her to participate in the civil war on the 'other side'. The fluidity of her identity is signalled by a scene in which she quickly hides her cross necklace and puts on a headscarf to approach a group of Muslims.

The writing, adapted from a play, it is perhaps too 'literary': 'L'enfance est un couteau planté dans la gorge' is great writing, but it rings false in the film's setting. (Incidentally, I was pleased to discover my French appears to have gone from abysmal to merely bad, as I was able to understand most of the French dialogue.) The often over-elaborate style points to the film's mythic quality: though rooted in the Lebanese Civil War, it becomes a parable of conflict in the region.

Québec, 2009: at the opening of the will, Jeanne Marwan (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and her brother Simon (Maxim Gaudette) discover that their recently deceased mother wants them to pass on letters to their father, whom they believed dead, and their brother, of whose existence they were unaware. Simon, angry at his mother's unusual request, refuses to return to the unspecified Middle Eastern country, but Jeanne decides to find out the truth in a country whose language she doesn't even speak.

This is interwoven with the story of her mother, Nawal Marwan (Lubna Azabal), a Christian from the south of the country, who in around 1970 conducts a love affair with a Muslim refugee. Members of her community kill her lover, but Nawal is already pregnant. She consents, ath the insistence of her grandmother, to give her newborn son to an orphanage and is sent away to university. As the country descends into sectarian strife, she leaves in search of her son but finds the orphanage destroyed. Pretending to be a Muslim for safety, she travels in a group that is eventually massacred by Christian militias. Having escaped only by revealing she is a Christian, Nawal joins a Muslim warlord's forces to wreak vengeance on the killers.

For much of Incendies, I was confused by the film's refuseal to name its setting, for the fictional Middle Eastern country is clearly Lebanon, the place of Wajdi Mouawad's birth. The specific situation of a civil war between Christian and Muslim militias over large numbers of refugees in the south, interrupted by a 'foreign invasion', is not what you'd call vague. By the end I understood. There is a plot twist that is grossly unlikely 'in reality', but brings home the theme of the film:

Jeanne and Simon's brother (Abdelghafour Elaaziz) is also their father, Nawal's son who, rescued from the destruction of his orphanage by a warlord, became a soldier and, after switching sides, eventually a torturer in the service of the government. In this capacity he raped his mother, rendering her pregnant. Further, he no longer lives in Lebanon, having left the country for Québec after the conclusion of the civil war.

This twist, an allusion to Greek myth, necessarily throws the film into unreality. Nor, for a film about Lebanon, is Incendies terribly interested in judging that conflict: it is neither pro- nor anti-sectarian, but treats the events of civil war as fate. This attitude is best encapsulated in the retired Muslim warlord Wallat Chamseddine (Mohamed Majd, in a terrific scene-stealing performance), who is neither regretful nor proud of his actions, only wary of the possible consequences. Incendies depicts the civil war as terrible but nonetheless unalterable: its focus is on family shaped by conflict.

All the same, Incendies is a harrowing indictment of inhumanity. A number of scenes dealing with rape as prison torture and its aftermath are very difficult to watch, as is the massacre of a passenger bus by militias, including the shooting of a child. The acting is excellent, especially Lubna Azabal, who portrays Nawal as a person driven by love and, increasingly, revenge for her suffering that leads her to participate in the civil war on the 'other side'. The fluidity of her identity is signalled by a scene in which she quickly hides her cross necklace and puts on a headscarf to approach a group of Muslims.

The writing, adapted from a play, it is perhaps too 'literary': 'L'enfance est un couteau planté dans la gorge' is great writing, but it rings false in the film's setting. (Incidentally, I was pleased to discover my French appears to have gone from abysmal to merely bad, as I was able to understand most of the French dialogue.) The often over-elaborate style points to the film's mythic quality: though rooted in the Lebanese Civil War, it becomes a parable of conflict in the region.

Wednesday, 5 October 2011

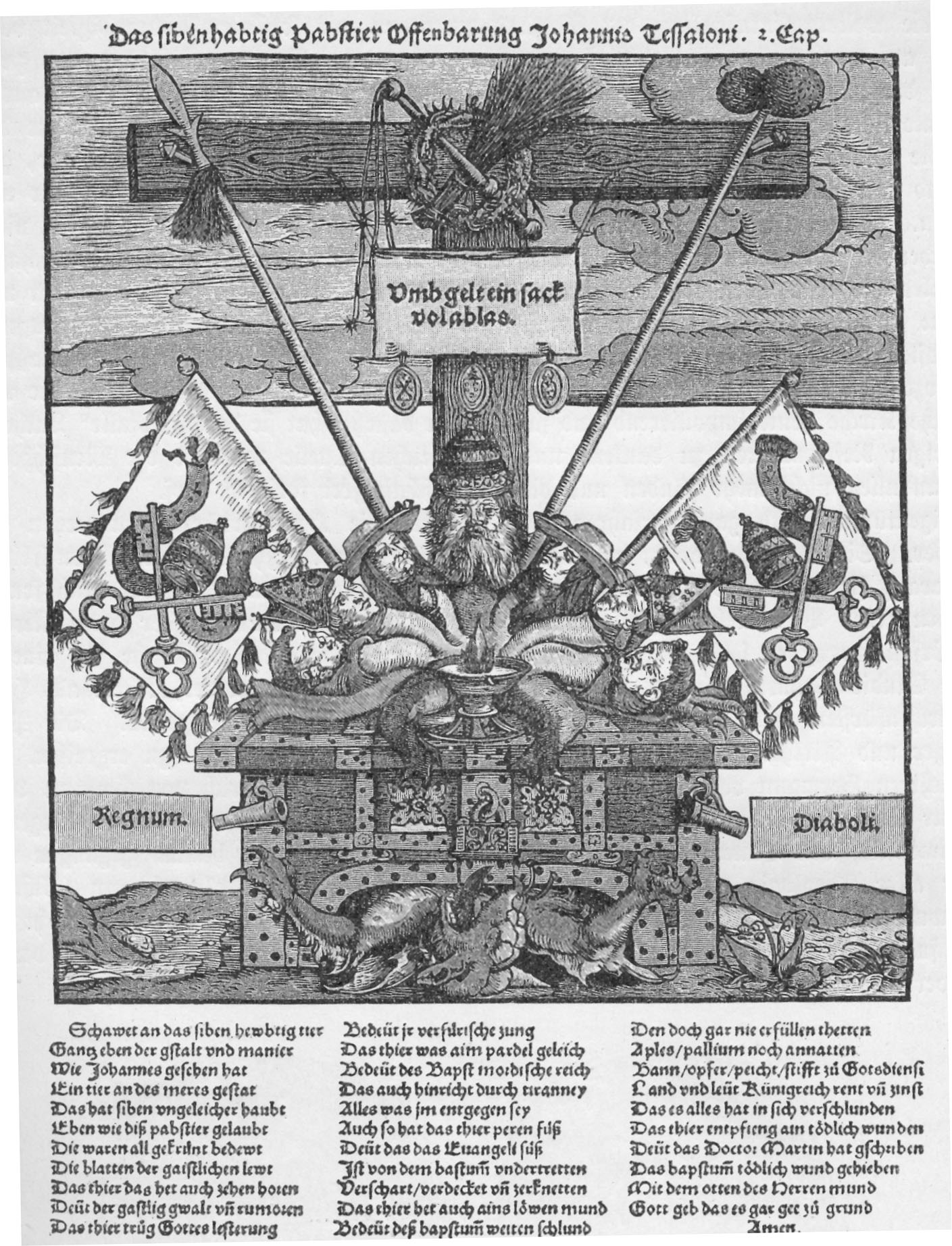

Against the anti-papists

(Note: this is an English paraphrase of an earlier post.)

The Left Party took a clear position on the pope's recent visit to Germany: half its MPs were to leave the room during the pope's speech before the Bundestag. I believe this attitude, widespread among the German Left both within and without parliament, is wrong both theoretically and strategically. The following is intended as a kick-off to a left-wing response to no-to-popery rhetoric in Germany: a critique of the critique of the pope, if you will.

Last year's papal visit to Britain, until recently my home, was similarly contested. At the time, Simon Hewitt outlined why hostility to the pope was suspect, but his argument, rooted as it is in historical materialism, applies mostly to a British context. But just as in Britain, German anti-Catholicism would do well to understand its own history.

Germany, almost uniquely among the European states, is divided into two denominations of roughly equal size.* The religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ended in a draw. The decline of imperial authority left no power above the princes, who proceeded to enforce uniform religious observance among their subjects. (It may have been for this reason that my Protestant ancestors left Upper Austria for Pomerania in the early eighteenth century.) After Prussia expelled Austria from the German Confederation, sixteen million Catholics remained in the newly unified German state: mostly in the south and west, in Ermland, Upper Silesia and the Polish border regions - beside twenty-eight million Protestants.

The Hohenzollern emperors were none too fond of these Catholics. They suspected them, the 'inner France', of conspiring with foreign powers and branded them 'enemies of the Reich'. Bismarck waged a protracted war of position - the Kulturkampf of the 1870s - against the Catholic Church. In short, Catholicism served the rulers of the Junker State as an imaginary enemy to secure their own power. Catholics fought back in the political arena through the Centre Party; many also joined the fledgling Social Democrats. At the same time, German nationalists in Austria-Hungary founded the 'Away from Rome' movement, combining virulent anti-Catholicism with antisemitism; protofascists like Georg von Schönerer converted to Protestantism.

Though officially neutral with respect to religion, Nazism was suspicious of the Catholic Church as a 'foreign' power from the beginning. In Catholic regions the Nazis never achieved the electoral breakthroughs that made the rural Protestant North their stronghold. In his infamous Myth of the Twentieth Century, Alfred Rosenberg claimed the Papacy descended from the haruspices - Etruscan soothsayers - and was thus of Asiatic, 'non-Aryan' origin. In western Germany, Catholicism only won equality and the capacity to contribute equally to public life after 1945.

Of course most latter-day anti-papists will be appalled at the unsavoury history of German anti-Catholicism: many, indeed, will not be familiar with it. Most of those hostile to the papal visit are of a generally secular frame of mind rather than hailing from a traditionally Protestant backgrounds. Either way hostility to the Catholic Church is not neutral terrain: any critique of the pope must formulate a response to the historical persecution of Catholics and unequivocally defend Catholics' enduring right to practise their faith in Germany.

Rejecting simplistic criticisms of the pope does not, of course, mean a blithe acceptance of the Vatican's teachings. Critics are right to lambaste Rome's stance on gender and sexuality as well as its treatment of the abuse scandal. As a Protestant, I also have fairly wide-ranging disagreements with Catholic teachings, from salvation to ecclesiology, the Eucharist and the use of images. None of that means, however, that one shouldn't invite the pope and hear him out. Not to mention that anyone who rejects the pope must be consistent: will he or she show the same zeal protesting President Obama, who is responsible for the deaths of thousands through drone attacks - which, however hostile, no-one could quite claim of the pope?

Liberal secularists opposing Protestants and Catholics as well as Muslims and religious Jews must be prepared to be self-critical and accept that, just like the Christianity of yore, their agitation has frequently been exploited in the cause of imperial aggression in recent years. Western Crusaders like Henryk Broder and Christopher Hitchens use a critique of religion to justify the invasion of Muslim countries as well as the continuing occupation and colonisation of Palestine. Secularism must be as wary of its false friends as it is of its supposed or real enemies. It must be critical of its own vocabulary and accept that it is counter-productive to stereotype Christians as, in the admirable words of Professor Dawkins, 'dyed-in-the-wool faith-heads'. Painting Joseph Ratzinger, a highly intelligent theologian, as an out-of-touch fuddy-duddy won't do much for anyone's credibility.

Most varieties of secularism find their origin not in Marxism but in a - particular and arguably wrong - interpretation of the Enlightenment, and the Left should be wary of applying them uncritically. Marx's real critique of religion cannot be separated from his critique of the social order, as a quick glance at the Introduction to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right will show:

But left-wing anti-papism is wrong not only in theory but also in practice. The Left Party has struggled for years to overcome its own east-west division: a mass party in eastern Germany but often the weakest of five parliamentary parties in the West, it is faced by the task of establishing itself among the West German working class. The most industrialised regions of the West (the Ruhr and the Rhineland), however, are also among the country's most strongly Catholic. Spicing up democratic socialism with God-is-dead sloganeering is self-sabotage. Left-wing politics must approach workers without prejudice, not condemn their beliefs, whatever they may be, as antediluvian.** It must engage real human beings, not the sort it would like in a perfect world. The party oddly has no problem grasping this when it comes to Iraq or Palestine, which should make one at least a little uneasy.

In other news, the decline of Christianity in Germany has led to strange side-effects. When the pope declined to advance the ecumenical integration of the churches, the press considered this a 'disappointment' to Protestants, whose hopes were apparently 'dashed' by the Pontiff. It would appear that when he said he felt closer to the Orthodox than to the Protestant churches, the pope made Protestant bishops cry. One might imagine the Eastern and Lutheran churches as prodigal sons competing for the approval of a displeased father and eager to move back into his house at the earliest opportunity. Well, I must announce my disappointment is somewhat limited: the Protestant tradition, be it Lutheran or Calvinist, has long been sufficiently strong to survive without a papal blessing. We'll live.

*Yugoslavia and Ireland are somewhat similar in this respect.

** Of course there are limits: the Left must always be a force against racism and sexism among workers, for example, which are morally unacceptable and weaken the working class.

The Left Party took a clear position on the pope's recent visit to Germany: half its MPs were to leave the room during the pope's speech before the Bundestag. I believe this attitude, widespread among the German Left both within and without parliament, is wrong both theoretically and strategically. The following is intended as a kick-off to a left-wing response to no-to-popery rhetoric in Germany: a critique of the critique of the pope, if you will.

Last year's papal visit to Britain, until recently my home, was similarly contested. At the time, Simon Hewitt outlined why hostility to the pope was suspect, but his argument, rooted as it is in historical materialism, applies mostly to a British context. But just as in Britain, German anti-Catholicism would do well to understand its own history.

Germany, almost uniquely among the European states, is divided into two denominations of roughly equal size.* The religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ended in a draw. The decline of imperial authority left no power above the princes, who proceeded to enforce uniform religious observance among their subjects. (It may have been for this reason that my Protestant ancestors left Upper Austria for Pomerania in the early eighteenth century.) After Prussia expelled Austria from the German Confederation, sixteen million Catholics remained in the newly unified German state: mostly in the south and west, in Ermland, Upper Silesia and the Polish border regions - beside twenty-eight million Protestants.

The Hohenzollern emperors were none too fond of these Catholics. They suspected them, the 'inner France', of conspiring with foreign powers and branded them 'enemies of the Reich'. Bismarck waged a protracted war of position - the Kulturkampf of the 1870s - against the Catholic Church. In short, Catholicism served the rulers of the Junker State as an imaginary enemy to secure their own power. Catholics fought back in the political arena through the Centre Party; many also joined the fledgling Social Democrats. At the same time, German nationalists in Austria-Hungary founded the 'Away from Rome' movement, combining virulent anti-Catholicism with antisemitism; protofascists like Georg von Schönerer converted to Protestantism.

Though officially neutral with respect to religion, Nazism was suspicious of the Catholic Church as a 'foreign' power from the beginning. In Catholic regions the Nazis never achieved the electoral breakthroughs that made the rural Protestant North their stronghold. In his infamous Myth of the Twentieth Century, Alfred Rosenberg claimed the Papacy descended from the haruspices - Etruscan soothsayers - and was thus of Asiatic, 'non-Aryan' origin. In western Germany, Catholicism only won equality and the capacity to contribute equally to public life after 1945.

Of course most latter-day anti-papists will be appalled at the unsavoury history of German anti-Catholicism: many, indeed, will not be familiar with it. Most of those hostile to the papal visit are of a generally secular frame of mind rather than hailing from a traditionally Protestant backgrounds. Either way hostility to the Catholic Church is not neutral terrain: any critique of the pope must formulate a response to the historical persecution of Catholics and unequivocally defend Catholics' enduring right to practise their faith in Germany.

Rejecting simplistic criticisms of the pope does not, of course, mean a blithe acceptance of the Vatican's teachings. Critics are right to lambaste Rome's stance on gender and sexuality as well as its treatment of the abuse scandal. As a Protestant, I also have fairly wide-ranging disagreements with Catholic teachings, from salvation to ecclesiology, the Eucharist and the use of images. None of that means, however, that one shouldn't invite the pope and hear him out. Not to mention that anyone who rejects the pope must be consistent: will he or she show the same zeal protesting President Obama, who is responsible for the deaths of thousands through drone attacks - which, however hostile, no-one could quite claim of the pope?

Liberal secularists opposing Protestants and Catholics as well as Muslims and religious Jews must be prepared to be self-critical and accept that, just like the Christianity of yore, their agitation has frequently been exploited in the cause of imperial aggression in recent years. Western Crusaders like Henryk Broder and Christopher Hitchens use a critique of religion to justify the invasion of Muslim countries as well as the continuing occupation and colonisation of Palestine. Secularism must be as wary of its false friends as it is of its supposed or real enemies. It must be critical of its own vocabulary and accept that it is counter-productive to stereotype Christians as, in the admirable words of Professor Dawkins, 'dyed-in-the-wool faith-heads'. Painting Joseph Ratzinger, a highly intelligent theologian, as an out-of-touch fuddy-duddy won't do much for anyone's credibility.

Most varieties of secularism find their origin not in Marxism but in a - particular and arguably wrong - interpretation of the Enlightenment, and the Left should be wary of applying them uncritically. Marx's real critique of religion cannot be separated from his critique of the social order, as a quick glance at the Introduction to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right will show:

The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man. Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again. But man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man – state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopaedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d’honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal basis of consolation and justification. It is the fantastic realisation of the human essence since the human essence has not acquired any true reality. The struggle against religion is, therefore, indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.Unlike Marx I do not believe 'religion' - which Marx rather unacceptably generalises as a universal phenomenon - to be an illusion, but the main thrust of Marx's argument is hard to argue with. Proclaiming the end of religion without at the same time fighting for the end of a state of affairs that leads people to long for a less terrible Beyond is not just an admission of impotence, but apologetics for the vale of tears. Unlike liberal atheism Marxism dissolves superstition into history, not vice versa: it seeks to overthrow the present society rather than pointlessly demand that people should bear it without illusions.

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

But left-wing anti-papism is wrong not only in theory but also in practice. The Left Party has struggled for years to overcome its own east-west division: a mass party in eastern Germany but often the weakest of five parliamentary parties in the West, it is faced by the task of establishing itself among the West German working class. The most industrialised regions of the West (the Ruhr and the Rhineland), however, are also among the country's most strongly Catholic. Spicing up democratic socialism with God-is-dead sloganeering is self-sabotage. Left-wing politics must approach workers without prejudice, not condemn their beliefs, whatever they may be, as antediluvian.** It must engage real human beings, not the sort it would like in a perfect world. The party oddly has no problem grasping this when it comes to Iraq or Palestine, which should make one at least a little uneasy.

In other news, the decline of Christianity in Germany has led to strange side-effects. When the pope declined to advance the ecumenical integration of the churches, the press considered this a 'disappointment' to Protestants, whose hopes were apparently 'dashed' by the Pontiff. It would appear that when he said he felt closer to the Orthodox than to the Protestant churches, the pope made Protestant bishops cry. One might imagine the Eastern and Lutheran churches as prodigal sons competing for the approval of a displeased father and eager to move back into his house at the earliest opportunity. Well, I must announce my disappointment is somewhat limited: the Protestant tradition, be it Lutheran or Calvinist, has long been sufficiently strong to survive without a papal blessing. We'll live.

*Yugoslavia and Ireland are somewhat similar in this respect.

** Of course there are limits: the Left must always be a force against racism and sexism among workers, for example, which are morally unacceptable and weaken the working class.

Labels:

Christianity,

die Linke,

Germany,

historical materialism,

history,

Marxism,

religion,

Roman Catholicism,

socialism

Sunday, 25 September 2011

Los von Rom? Eine Kritik der Papstkritik

Die Linke bezog klar Stellung zum Papstbesuch. Die Hälfte ihrer Abgeordneten wollte zur Papstrede im Bundestag den Saal verlassen. Ich halte diese Ablehnung, die auch außerparlamentarisch in linken Kreisen weit verbreitet ist, für theoretisch und strategisch falsch. Wir bedürfen einer linken Antwort auf die Nein-zum-Papst-Rhetorik - eine Kritik der Papstkritik, wenn man so will.

Auch die Reise des Papstes nach England, bis vor kurzem meine Wahlheimat, war umstritten. Simon Hewitt legte damals dar, warum ihm die Gegnerschaft suspekt war, allerdings fußt sein Argument auf historischem Materialismus und damit einem britischen Kontext, der für Deutschland nicht gilt. Der deutsche Antikatholizismus täte gut daran, die eigene Geschichte zu verstehen.

Deutschland ist in Europa fast einzigartig in seiner Teilung in zwei Konfessionen ähnlicher Größe.* In den Religionskriegen des sechzehnten und siebzehnten Jahrhunderts gelang keiner Seite der Sieg, und durch die Zermürbung der Kaisermacht gab es in Deutschland bald gar keine Instanz über den einzelnen Fürstenhäusern, die nach dem Prinzip cuius regio, eius religio ihre Untertanen dem eigenen Glauben unterwarfen. (Vielleicht aus diesem Grunde wanderten meine evangelischen Vorfahren im frühen achtzehnten Jahrhundert aus Oberösterreich nach Pommern aus.) Nachdem Preußen Österreich aus Deutschland drängte, verblieben im Kaiserreich sechzehn Millionen Katholiken - vor allem im Süden und Westen, im Ermland, in Oberschlesien und den polnischen Grenzgebieten - zu achtundzwanzig Millionen Protestanten.

Den Hohenzollern waren diese Katholiken nicht lieb, sie wurden als "inneres Frankreich" des Sympathisantentums mit äußeren Mächten verdächtigt, als Reichsfeinde gebrandmarkt und im Kulturkampf von Bismarck bekriegt: kurzum, die Kirche diente den Herrschern des Junkerstaates als Scheinfeind, um die eigene Macht zu sichern. Katholiken wehrten sich politisch durch die Zentrumspartei, viele traten auch der SPD bei. Zugleich formierte sich unter den Deutschnationalen Österreich-Ungarns die Los-von-Rom-Bewegung, die Antikatholizismus mit Antisemitismus verband. Protofaschisten wie Georg von Schönerer traten zu dieser Zeit zum Protestantismus über.

War der Nationalsozialismus offiziell konfessionsneutral, so stand er doch der katholischen Kirche von Anfang an als außerdeutscher Macht ablehnend gegenüber. Im katholischen Deutschland gelang den Nationalsozialisten niemals der Durchbruch, der das ländliche, evangelische Norddeutschland zu ihrer Hochburg zumindest nach Stimmenanteilen gemacht hatte. Alfred Rosenberg erklärte im Mythus des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts, das Papsttum sei aus den haruspices, den Wahrsagern der Etrusker, entstanden und somit asiatischen, "nichtarischen" Ursprungs. Erst nach 1945 gewann der Katholizismus im Westteil Deutschlands Gleichberechtigung und konnte auch zum Kulturleben der Bundesrepublik oft entscheidend beitragen.

Natürlich betrachten die meisten heutigen Papstgegner diese unschöne Geschichte des deutschen Antikatholizismus mit Abscheu, viele werden auch gar nichts davon wissen. Jedenfalls ist die Ablehnung der katholischen Kirche kein unbeflecktes Gelände: ein Nein zum Papstbesuch muß mit einem Ja zum Existenzrecht des Katholizismus in Deutschland einhergehen. Auch stammen die wenigsten Papstgegner aus dem Umfeld des klassischen Protestantismus, sondern sind allgemein säkular eingestellt. Dennoch muß jede Papstkritik zum historischen Antikatholizismus in Deutschland Stellung beziehen und Katholiken klarmachen, daß ihrem Glauben und Brauchtum nicht allgemein das Daseinsrecht abgesprochen wird.

Eine Kritik der Papstkritik bedeutet nun keineswegs das unbedingte Ja zu allen Lehren des Vatikans. Die Gegner haben ja recht damit, daß zum Beispiel die Sexual- und Geschlechterpolitik Roms, auch der Umgang mit dem Mißbrauchsskandal sehr unzureichend war. Ich als Protestant melde natürlich weitreichende theologische Differenzen mit dem Papst an, von der Erlösung zur Ekklesiologie, dem Abendmahl und dem Bilderstreit. Das heißt aber nicht, daß man den Papst nicht einladen und ihm höflich zuhören könnte. Und wer den Papst ablehnt, der muß sich die Frage nach der eigenen Prinzipienfestigkeit gefallen lassen: würden dieselben Menschen ebenso energisch gegen Präsident Obama protestieren, der immerhin Tausende Menschen in Pakistan durch Drohnenangriffe hat töten lassen - was man vom Papst ja nicht behaupten kann?

Die säkulare Religionskritik wendet sich unterschiedslos gegen Protestanten und Katholiken, auch gegen Muslime und religiöse Juden. Sie muß sich dabei kritisch zu sich selbst verhalten und sich eingestehen, daß ihre Position oft zu imperialistischen Zwecken mißbraucht wird, wie es einst mit dem Christentum geschah. Westliche Kreuzritter wie Christopher Hitchens und Henryk Broder rechtfertigen mit der Religionskritik den Überfall auf muslimische Länder ebenso wie die fortdauernde Besatzung und Kolonisierung Palästinas. Sie muß also von ihren falschen Freunden genauso Abstand nehmen wie von ihren vermeintlichen oder wahren Gegnern. Außerdem muß sie ihr eigenes Vokabular überprüfen und sich klarmachen, daß es ihr nicht hilft, Christen für verblendet oder dumm zu erklären. Wer einen hochintelligenten Theologen wie Joseph Ratzinger als zurückgeblieben abstempelt, hat ein Glaubwürdigkeitsproblem.

Die weitestverbreiteten Strömungen des Säkularismus entstehen nicht aus dem Marxismus, sondern aus einem falsch verstandenen liberalen Aufklärungsdenken, und sollten von der Linken darum nicht unkritisch angewandt werden. Marx' tatsächliche Religionskritik ist untrennbar mit der Gesellschaftskritik verbunden, wie in Zur Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie: Einleitung zusammengefaßt:

Aber die linke Papstkritik ist nicht nur theoretisch, sondern auch strategisch falsch. Die Linke bemüht sich seit Jahren, ihr West-Ost-Gefälle zu überwinden: im Osten Volkspartei, im Westen oft kleinste der parlamentarischen Parteien, muß sie unter den Arbeitern Westdeutschlands Fuß fassen. Nun sind aber die Industrieregionen Westdeutschlands, wie das Ruhrgebiet und Rheinland, unter den am stärksten katholischen Gegenden. Wer dort den demokratischen Sozialismus mit Gott-ist-tot-Parolen anreichert, stellt sich selbst ein Bein. Linke Politik sollte sich den Arbeitern vorurteilsfrei nähern und von ihnen lernen, nicht ihre Anschauungen von vornherein für vorsintflutlich erklären.** Sie muß den Schulterschluß mit wirklichen Menschen wagen, nicht mit solchen, wie sie sie gerne hätte. Das erkennt die Partei ja seltsamerweise auch, wenn es um Palästina oder den Irak geht, aber in Dortmund soll es aus irgendeinem Grunde (der ja, man vergesse es nicht, auch anrüchig sein kann) anders sein.

Der Schwund des Christentums in Deutschland hat übrigens eine merkwürdige Nebenwirkung. Die Absage, die der Papst dem weiteren Zusammenwachsen der Kirchen erteilte, wertet die Presse als "Enttäuschung" für Protestanten, deren Hoffnungen der Papst zunichte mache. Er fühle sich Orthodoxen näher als Protestanten, sagte der Papst und brachte damit, so möchte man meinen, evangelische Kirchenhäupter zum Weinen. Das klingt, als seien Ost- und Lutherkirchen verlorene Söhne, die um das Wohlwollen eines unzufriedenen Vaters wettbuhlen und am liebsten so bald wie möglich wieder bei ihm einziehen wollen. Ich darf vermelden, daß meine Enttäuschung sich in Grenzen hält: die protestantische Tradition, sei sie lutherisch oder calvinistisch, reicht längst aus, um auch ohne den Papstsegen fortzubestehen. Das überstehen wir schon.

* Jugoslawien und Irland ähneln Deutschland in dieser Hinsicht.

** Natürlich hat diese Einstellung Grenzen. Frauen- und Fremdenfeindlichkeit sind z.B. stets abzulehnen, da sie die Arbeiter teilen und schwächen.

UPDATE: An English paraphrase of this post can be found here.

Auch die Reise des Papstes nach England, bis vor kurzem meine Wahlheimat, war umstritten. Simon Hewitt legte damals dar, warum ihm die Gegnerschaft suspekt war, allerdings fußt sein Argument auf historischem Materialismus und damit einem britischen Kontext, der für Deutschland nicht gilt. Der deutsche Antikatholizismus täte gut daran, die eigene Geschichte zu verstehen.

Deutschland ist in Europa fast einzigartig in seiner Teilung in zwei Konfessionen ähnlicher Größe.* In den Religionskriegen des sechzehnten und siebzehnten Jahrhunderts gelang keiner Seite der Sieg, und durch die Zermürbung der Kaisermacht gab es in Deutschland bald gar keine Instanz über den einzelnen Fürstenhäusern, die nach dem Prinzip cuius regio, eius religio ihre Untertanen dem eigenen Glauben unterwarfen. (Vielleicht aus diesem Grunde wanderten meine evangelischen Vorfahren im frühen achtzehnten Jahrhundert aus Oberösterreich nach Pommern aus.) Nachdem Preußen Österreich aus Deutschland drängte, verblieben im Kaiserreich sechzehn Millionen Katholiken - vor allem im Süden und Westen, im Ermland, in Oberschlesien und den polnischen Grenzgebieten - zu achtundzwanzig Millionen Protestanten.

Den Hohenzollern waren diese Katholiken nicht lieb, sie wurden als "inneres Frankreich" des Sympathisantentums mit äußeren Mächten verdächtigt, als Reichsfeinde gebrandmarkt und im Kulturkampf von Bismarck bekriegt: kurzum, die Kirche diente den Herrschern des Junkerstaates als Scheinfeind, um die eigene Macht zu sichern. Katholiken wehrten sich politisch durch die Zentrumspartei, viele traten auch der SPD bei. Zugleich formierte sich unter den Deutschnationalen Österreich-Ungarns die Los-von-Rom-Bewegung, die Antikatholizismus mit Antisemitismus verband. Protofaschisten wie Georg von Schönerer traten zu dieser Zeit zum Protestantismus über.

War der Nationalsozialismus offiziell konfessionsneutral, so stand er doch der katholischen Kirche von Anfang an als außerdeutscher Macht ablehnend gegenüber. Im katholischen Deutschland gelang den Nationalsozialisten niemals der Durchbruch, der das ländliche, evangelische Norddeutschland zu ihrer Hochburg zumindest nach Stimmenanteilen gemacht hatte. Alfred Rosenberg erklärte im Mythus des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts, das Papsttum sei aus den haruspices, den Wahrsagern der Etrusker, entstanden und somit asiatischen, "nichtarischen" Ursprungs. Erst nach 1945 gewann der Katholizismus im Westteil Deutschlands Gleichberechtigung und konnte auch zum Kulturleben der Bundesrepublik oft entscheidend beitragen.

Natürlich betrachten die meisten heutigen Papstgegner diese unschöne Geschichte des deutschen Antikatholizismus mit Abscheu, viele werden auch gar nichts davon wissen. Jedenfalls ist die Ablehnung der katholischen Kirche kein unbeflecktes Gelände: ein Nein zum Papstbesuch muß mit einem Ja zum Existenzrecht des Katholizismus in Deutschland einhergehen. Auch stammen die wenigsten Papstgegner aus dem Umfeld des klassischen Protestantismus, sondern sind allgemein säkular eingestellt. Dennoch muß jede Papstkritik zum historischen Antikatholizismus in Deutschland Stellung beziehen und Katholiken klarmachen, daß ihrem Glauben und Brauchtum nicht allgemein das Daseinsrecht abgesprochen wird.

Eine Kritik der Papstkritik bedeutet nun keineswegs das unbedingte Ja zu allen Lehren des Vatikans. Die Gegner haben ja recht damit, daß zum Beispiel die Sexual- und Geschlechterpolitik Roms, auch der Umgang mit dem Mißbrauchsskandal sehr unzureichend war. Ich als Protestant melde natürlich weitreichende theologische Differenzen mit dem Papst an, von der Erlösung zur Ekklesiologie, dem Abendmahl und dem Bilderstreit. Das heißt aber nicht, daß man den Papst nicht einladen und ihm höflich zuhören könnte. Und wer den Papst ablehnt, der muß sich die Frage nach der eigenen Prinzipienfestigkeit gefallen lassen: würden dieselben Menschen ebenso energisch gegen Präsident Obama protestieren, der immerhin Tausende Menschen in Pakistan durch Drohnenangriffe hat töten lassen - was man vom Papst ja nicht behaupten kann?

Die säkulare Religionskritik wendet sich unterschiedslos gegen Protestanten und Katholiken, auch gegen Muslime und religiöse Juden. Sie muß sich dabei kritisch zu sich selbst verhalten und sich eingestehen, daß ihre Position oft zu imperialistischen Zwecken mißbraucht wird, wie es einst mit dem Christentum geschah. Westliche Kreuzritter wie Christopher Hitchens und Henryk Broder rechtfertigen mit der Religionskritik den Überfall auf muslimische Länder ebenso wie die fortdauernde Besatzung und Kolonisierung Palästinas. Sie muß also von ihren falschen Freunden genauso Abstand nehmen wie von ihren vermeintlichen oder wahren Gegnern. Außerdem muß sie ihr eigenes Vokabular überprüfen und sich klarmachen, daß es ihr nicht hilft, Christen für verblendet oder dumm zu erklären. Wer einen hochintelligenten Theologen wie Joseph Ratzinger als zurückgeblieben abstempelt, hat ein Glaubwürdigkeitsproblem.

Die weitestverbreiteten Strömungen des Säkularismus entstehen nicht aus dem Marxismus, sondern aus einem falsch verstandenen liberalen Aufklärungsdenken, und sollten von der Linken darum nicht unkritisch angewandt werden. Marx' tatsächliche Religionskritik ist untrennbar mit der Gesellschaftskritik verbunden, wie in Zur Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie: Einleitung zusammengefaßt:

Das Fundament der irreligiösen Kritik ist: Der Mensch macht die Religion, die Religion macht nicht den Menschen. Und zwar ist die Religion das Selbstbewußtsein und das Selbstgefühl des Menschen, der sich selbst entweder noch nicht erworben oder schon wieder verloren hat. Aber der Mensch, das ist kein abstraktes, außer der Welt hockendes Wesen. Der Mensch, das ist die Welt des Menschen, Staat, Sozietät. Dieser Staat, diese Sozietät produzieren die Religion, ein verkehrtes Weltbewußtsein, weil sie eine verkehrte Welt sind. Die Religion ist die allgemeine Theorie dieser Welt, ihr enzyklopädisches Kompendium, ihre Logik in populärer Form, ihr spiritualistischer Point-d'honneur, ihr Enthusiasmus, ihre moralische Sanktion, ihre feierliche Ergänzung, ihr allgemeiner Trost- und Rechtfertigungsgrund. Sie ist die phantastische Verwirklichung des menschlichen Wesens, weil das menschliche Wesen keine wahre Wirklichkeit besitzt. Der Kampf gegen die Religion ist also mittelbar der Kampf gegen jene Welt, deren geistiges Aroma die Religion ist.Zwar halte ich im Gegensatz zu Marx "die Religion", die Marx unzulässig als allgemeines Phänomen zusammenfaßt, nicht für eine Illusion. Dem Hauptargument der Marxschen Religionskritik aber kann ich zustimmen. Wer das Ende der Religion proklamiert, ohne zugleich für das Ende aller Zustände, die den Menschen auf ein betteres Jenseits hoffen läßt, zu kämpfen, der ist nicht nur kraftlos, sondern Apologist des Jammertals. Im Gegensatz zum liberalen Atheismus leitet marxistische Kritik nicht die Geschichte aus dem Aberglauben, sondern den Aberglauben aus der Geschichte ab; sie sucht die gegenwärtige Gesellschaft aufzuheben, statt sinnlos zu verlangen, daß der Mensch sie illusionslos zu ertragen habe.

Das religiöse Elend ist in einem der Ausdruck des wirklichen Elendes und in einem die Protestation gegen das wirkliche Elend. Die Religion ist der Seufzer der bedrängten Kreatur, das Gemüt einer herzlosen Welt, wie sie der Geist geistloser Zustände ist. Sie ist das Opium des Volkes.

Die Aufhebung der Religion als des illusorischen Glücks des Volkes ist die Forderung seines wirklichen Glücks. Die Forderung, die Illusionen über einen Zustand aufzugeben, ist die Forderung, einen Zustand aufzugeben, der der Illusionen bedarf. Die Kritik der Religion ist also im Keim die Kritik des Jammertales, dessen Heiligenschein die Religion ist.

Aber die linke Papstkritik ist nicht nur theoretisch, sondern auch strategisch falsch. Die Linke bemüht sich seit Jahren, ihr West-Ost-Gefälle zu überwinden: im Osten Volkspartei, im Westen oft kleinste der parlamentarischen Parteien, muß sie unter den Arbeitern Westdeutschlands Fuß fassen. Nun sind aber die Industrieregionen Westdeutschlands, wie das Ruhrgebiet und Rheinland, unter den am stärksten katholischen Gegenden. Wer dort den demokratischen Sozialismus mit Gott-ist-tot-Parolen anreichert, stellt sich selbst ein Bein. Linke Politik sollte sich den Arbeitern vorurteilsfrei nähern und von ihnen lernen, nicht ihre Anschauungen von vornherein für vorsintflutlich erklären.** Sie muß den Schulterschluß mit wirklichen Menschen wagen, nicht mit solchen, wie sie sie gerne hätte. Das erkennt die Partei ja seltsamerweise auch, wenn es um Palästina oder den Irak geht, aber in Dortmund soll es aus irgendeinem Grunde (der ja, man vergesse es nicht, auch anrüchig sein kann) anders sein.

Der Schwund des Christentums in Deutschland hat übrigens eine merkwürdige Nebenwirkung. Die Absage, die der Papst dem weiteren Zusammenwachsen der Kirchen erteilte, wertet die Presse als "Enttäuschung" für Protestanten, deren Hoffnungen der Papst zunichte mache. Er fühle sich Orthodoxen näher als Protestanten, sagte der Papst und brachte damit, so möchte man meinen, evangelische Kirchenhäupter zum Weinen. Das klingt, als seien Ost- und Lutherkirchen verlorene Söhne, die um das Wohlwollen eines unzufriedenen Vaters wettbuhlen und am liebsten so bald wie möglich wieder bei ihm einziehen wollen. Ich darf vermelden, daß meine Enttäuschung sich in Grenzen hält: die protestantische Tradition, sei sie lutherisch oder calvinistisch, reicht längst aus, um auch ohne den Papstsegen fortzubestehen. Das überstehen wir schon.

* Jugoslawien und Irland ähneln Deutschland in dieser Hinsicht.

** Natürlich hat diese Einstellung Grenzen. Frauen- und Fremdenfeindlichkeit sind z.B. stets abzulehnen, da sie die Arbeiter teilen und schwächen.

UPDATE: An English paraphrase of this post can be found here.

Labels:

Christianity,

deutsch,

die Linke,

Germany,

historical materialism,

history,

Marxism,

religion,

Roman Catholicism,

socialism

Tuesday, 7 June 2011

Fleischhauer schlägt wieder zu!

Daß ich regelmäßig die Spiegel Online-Kolumne des Herrn Fleischhauer lese, mag auf Persönlichkeitsprobleme hindeuten. Fleischhauer liest man am besten in kleinen Dosen, sonst erschöpft sich der eigene Zorn an der schieren Gemeinheit und Dummheit seiner Polemik. Der feine Herr ist die Abteilung Attacke einer gewissen Art rechten Bürgers, der sich bestens frisiert und in edle Anzüge gekleidet über den realitätsfernen Pöbel lustig macht. Der nämlich - man glaubt es kaum! - verlangt Dinge wie Atomausstieg, Frieden, ein Ende des Klassenkampfes von oben. Der Linke als Träumer ist der Mittelpunkt der Rhetorik Fleischhauers, der sich selbst als Bewahrer der Aufklärung sieht. Politik ist die Herrschaft der aufgeklärten Elite über den unwissenden und nichts wissenwollenden Gefühlsmenschen.

So in seiner neuesten Kolumne, in der Herr F. den Kirchentag in Dresden kritisiert. Für mich als Christen und Sozialisten ist das Thema doppelt interessant. Daß Fleischhauer die EKD nur als eine der "Vorfeldorganisationen" der ihm verhaßten Grünen ansieht, ist kurios, entspricht aber seiner kämpferischen Grundhaltung. Die von ihm zitierten Resolutionen - "Alternativen zum Wirtschaftswachstum", Schutz der Roma vor Ausweisung und das "Recht auf ein Leben ohne Bedrohung durch atomare Strahlen" sind vernünftig; allein den Antrag an die Kirchenleitung, das Schicksal der "der als Hexen hingerichteten Bürger und Bürgerinnen" aufzuarbeiten, scheint mir ein bißchen lächerlich. Was wendet nun Fleischhauer gegen besagte Resolutionen ein?

Vor allem dies: die Anträge zeigten einen "Stolz auf das unbedarfte Denken" auf.

Stimmt es, daß "es auf Dauer schwierig sein dürfte, ein Industrieland ganz ohne verlässliche Energiequellen am Laufen zu halten"? Was heißt "verläßlich"? Verläßlich ist bei fossiler Energie nur die zunehmende Umweltzerstörung nebst ständig drohender Katastrophen, d.h. die Vernichtung unseres Lebensraumes. Damit ist "ein Industrieland" vielleicht "am Laufen zu halten", die Menschen aber nicht. Das ist durchaus logisch: der Bourgeois setzt die Reproduktion seiner Macht gleich mit dem Wohlergehen der Gesellschaft und arbeitete darum im Namen des Fortschritts einst Kinder zu Tode (was nun angenehmerweise größtenteils anderswo geschieht - zum Glück gibt es ja die räumliche Distanz).

Marcuse charakterisiert das als eindimensionales Denken, die Anwendung tadelloser Logik und Rationalität, die sich beim kritischen Hinsehen als katastrophal unvernünftig erweist. Ständiges explosives Wirtschaftswachstum mag den Herren Wirtschaftsweisen vernünftig erscheinen, ja vielleicht sogar eine Existenzbedingung des heutigen Kapitalismus sein. Weil die Ressourcen der Erde aber endlich sind, wird die Forderung nach größerem Wirtschaftswachstum zur Forderung nach der beschleunigten Selbstvernichtung der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft - was so schlimm nicht wäre, wenn sie uns allesamt nicht mit ins Grab risse. Nichts ist unvernünftiger als die Position der Kanzlerin, die uns schnellstens in die Vorkrisenzeit zurückversetzen will, als wir eben vor der Krise standen.

Auch das brutale Absenken des allgemeinen Lebensstandards, die wir gerade in Großbritannien und anderen Ländern erleben, die gewaltsame Umverteilung von unten nach oben scheint sinnvoll, will man den stotternden Motor des Kapitalismus wieder in Fahrt zu bringen (vorausgesetzt, man hält Binnennachfrage für unwichtig). Wer aber am Wohlergehen des Menschen und nicht am Kontostand der Herrscher ansetzt, wird diese "Vernunft" höchst unvernünftig finden. Dazu muß man keineswegs nur mit dem Herzen denken. Die Logik des Kapitalismus läßt sich verteidigen, aber nur "by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties". Darum die beispiellose Propagandaoffensive der letzten Jahre.

So löst sich Fleischhauers Kritik an "sentimentalem" Wunschdenken letztlich auf in Kritik alles Denkens, das beim Menschen statt beim Gewinn des Kapitalisten ansetzt. Wer den Menschen als Subjekt und nicht nur als Instrument wahrnimmt, kann Fleischhauer nicht folgen.

Gegen Ende seines Auswurfs aber gelingt es Fleischhauer dann doch, eine interessante Debatte anzustoßen. Er sieht das kirchliche Interesse an weltlichen Themen als fatale Selbstschwächung:

Erstens hat es niemals ein Zeitalter gegeben, in dem Kirchen sich unpolitisch verhalten hätten - und das nicht nur, weil Politik zwangsläufig alle Lebensbereiche durchdringt. Kirchen sind immer politisch positioniert. Die Kirchen des Kaiserreichs lehrten statt der Subversion, die Fleischhauer mißfällt, eben Ruhe, Gehorsam und Ordnung als Christenpflicht und halfen damit dem status quo in Deutschland. Luther verfaßte neben der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen auch An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation und griff damit religiös-politische Zustände an. Eine Art politische Neutralität der Kirche ist nur durch Staatsterror zu erreichen.

Zweitens ist die Trennung zwischen "Religion" und "Politik" fiktiv. Es gibt keine religiöse Sphäre, in der es nur um Engelein und Abendmahl ginge, die Gesellschaft insgesamt aber fein säuberlich außen vor bliebe. In der Gottesherrschaft des Alten Testaments ist das unübersehbar, aber auch das Evangelium ist zutiefst politisch. Die Werte, die Gläubige ihrer Religion entnehmen, beeinflussen ihr politisches Engagement, und die Gesellschaftskonstellation durchdringt umgekehrt die Kirche. Die scheinbare Trennung von Religion und Politik, Staat und Kirche ist dafür sogar das beste Beispiel, denn sie ist das unmittelbare Produkt der kapitalistischen gesellschaftlichen Revolution (wozu siehe Marx, Zur Judenfrage).

Stimmt es nun, daß "[k]aum ein Pastor [sich noch] traut..., ungeniert von Himmel und Hölle zu sprechen"? Damit hat Fleischhauer in meiner Erfahrung allerdings recht. Und wenn die Kirche also zur Gruppentherapie und Ethikstunde verkommt, in der man sich der Bibel schämt, wie vielerorts geschehen, macht sie sich tatsächlich selbst überflüssig. Aber daraus läßt sich keineswegs schließen, daß die Kirche gesellschaftliches Engagement aufgeben und nur noch von Kreuzigung und Höllenfeuer zu erzählen hätte. Ein solcher Rückzug wäre wie schon gesagt ohnehin unmöglich. Vielmehr gibt das Evangelium der Kirche eine einzigartige Perspektive auf gesellschaftliche Fragen und kann einen Dialog zwischen Gott und Welt anstoßen, der beide bereichert.

Jesus' Spruch, wonach ein Kamel leichter durch ein Nadelöhr als ein Reicher ins Himmelreich gehe, ist wenig tröstlich für die Herrschaft. Jesaja 58 zerlegt die zurschaugestellte Frömmigkeit jener Elite, die zugleich die Armen auspreßt. Das Evangelium - daß alle Menschen in ihrem Wert, aber auch ihrer Schuld vor Gott gleich sind und Christus als Mensch lebte, hungerte, litt und für uns starb - gehört keineswegs jenen, die aus ihm Akzeptanz der Gesellschaftsordnung ablesen wollen. Vielmehr leitet es zur Kritik an. Diese Kritik - den Dialog zwischen Wort und Welt - kann die Kirche führen. Daß sie sich in Dresden in die großen Gesellschaftsfragen einmischt, ist gut für die Kirche und gut für die Gesellschaft.

So in seiner neuesten Kolumne, in der Herr F. den Kirchentag in Dresden kritisiert. Für mich als Christen und Sozialisten ist das Thema doppelt interessant. Daß Fleischhauer die EKD nur als eine der "Vorfeldorganisationen" der ihm verhaßten Grünen ansieht, ist kurios, entspricht aber seiner kämpferischen Grundhaltung. Die von ihm zitierten Resolutionen - "Alternativen zum Wirtschaftswachstum", Schutz der Roma vor Ausweisung und das "Recht auf ein Leben ohne Bedrohung durch atomare Strahlen" sind vernünftig; allein den Antrag an die Kirchenleitung, das Schicksal der "der als Hexen hingerichteten Bürger und Bürgerinnen" aufzuarbeiten, scheint mir ein bißchen lächerlich. Was wendet nun Fleischhauer gegen besagte Resolutionen ein?

Vor allem dies: die Anträge zeigten einen "Stolz auf das unbedarfte Denken" auf.

Mit dem Herzen zu denken beziehungsweise mit dem Kopf zu fühlen... gilt auf dieser Art von Veranstaltung als besondere Tugend. Mit der Aufklärung hat sich der Sentimentalismus nie wirklich anfreunden können, Rationalität muss seit langem mit dem Vorwurf leben, zynisch, kalt, ja irgendwie männlich zu sein. Der Stolz auf das unbedarfte Denken ist geradezu Signum der Gefühlstheologie: "Präreflektierte Unmittelbarkeit" sei doch "eigentlich ganz schön", verkündete Margot Käßmann zum Auftakt der grünen Tage in Dresden, womit sie zweifellos vielen Zuhörern aus dem - ja: Herzen - sprach.Und ganz unrecht hat Herr Fleischhauer hier gar nicht: tatsächlich hat sich "der Sentimentalismus" mit "der Aufklärung" nicht abfinden können. Hat nicht die Bourgeoisie "die heiligen Schauer der frommen Schwärmerei, der ritterlichen Begeisterung, der spießbürgerlichen Wehmut in dem eiskalten Wasser egoistischer Berechnung ertränkt" (Marx/Engels)? Aber der selbsternannte Hüter aufklärerischer Vernunft ist der eigentlich Unvernünftige.

Stimmt es, daß "es auf Dauer schwierig sein dürfte, ein Industrieland ganz ohne verlässliche Energiequellen am Laufen zu halten"? Was heißt "verläßlich"? Verläßlich ist bei fossiler Energie nur die zunehmende Umweltzerstörung nebst ständig drohender Katastrophen, d.h. die Vernichtung unseres Lebensraumes. Damit ist "ein Industrieland" vielleicht "am Laufen zu halten", die Menschen aber nicht. Das ist durchaus logisch: der Bourgeois setzt die Reproduktion seiner Macht gleich mit dem Wohlergehen der Gesellschaft und arbeitete darum im Namen des Fortschritts einst Kinder zu Tode (was nun angenehmerweise größtenteils anderswo geschieht - zum Glück gibt es ja die räumliche Distanz).

Marcuse charakterisiert das als eindimensionales Denken, die Anwendung tadelloser Logik und Rationalität, die sich beim kritischen Hinsehen als katastrophal unvernünftig erweist. Ständiges explosives Wirtschaftswachstum mag den Herren Wirtschaftsweisen vernünftig erscheinen, ja vielleicht sogar eine Existenzbedingung des heutigen Kapitalismus sein. Weil die Ressourcen der Erde aber endlich sind, wird die Forderung nach größerem Wirtschaftswachstum zur Forderung nach der beschleunigten Selbstvernichtung der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft - was so schlimm nicht wäre, wenn sie uns allesamt nicht mit ins Grab risse. Nichts ist unvernünftiger als die Position der Kanzlerin, die uns schnellstens in die Vorkrisenzeit zurückversetzen will, als wir eben vor der Krise standen.

Auch das brutale Absenken des allgemeinen Lebensstandards, die wir gerade in Großbritannien und anderen Ländern erleben, die gewaltsame Umverteilung von unten nach oben scheint sinnvoll, will man den stotternden Motor des Kapitalismus wieder in Fahrt zu bringen (vorausgesetzt, man hält Binnennachfrage für unwichtig). Wer aber am Wohlergehen des Menschen und nicht am Kontostand der Herrscher ansetzt, wird diese "Vernunft" höchst unvernünftig finden. Dazu muß man keineswegs nur mit dem Herzen denken. Die Logik des Kapitalismus läßt sich verteidigen, aber nur "by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties". Darum die beispiellose Propagandaoffensive der letzten Jahre.

So löst sich Fleischhauers Kritik an "sentimentalem" Wunschdenken letztlich auf in Kritik alles Denkens, das beim Menschen statt beim Gewinn des Kapitalisten ansetzt. Wer den Menschen als Subjekt und nicht nur als Instrument wahrnimmt, kann Fleischhauer nicht folgen.

Gegen Ende seines Auswurfs aber gelingt es Fleischhauer dann doch, eine interessante Debatte anzustoßen. Er sieht das kirchliche Interesse an weltlichen Themen als fatale Selbstschwächung:

Die Folgen der Selbstsäkularisierung sind heute an vielen Gottesdiensten ablesbar. Kaum ein Pastor traut sich noch, ungeniert von Himmel und Hölle zu sprechen, und wenn, dann ist das nur allegorisch gemeint, wie er sich hinzuzufügen beeilt. Stattdessen findet sich in jeder guten Sonntagspredigt die Litanei über den Kriegstreiber Amerika, die Schrecken der Globalisierung, das Elend der Hartz-IV-Empfänger.Fleischhauers Argument liegen zwei falsche Annahmen zugrunde.

Diese Diesseitsfixierung hat einen für die Kirche unschönen Nebeneffekt: Mit der Verschiebung des Erlösungshorizonts, der sich ganz aufs Heute richtet, setzt sie sich der Konkurrenz zu weltlichen Glaubensorganisationen aus, die dem Bedürfnis nach entschiedenem Handeln sehr viel besser nachkommen können. Warum nicht gleich Mitglied bei Greenpeace, Peta oder Amnesty werden?

Erstens hat es niemals ein Zeitalter gegeben, in dem Kirchen sich unpolitisch verhalten hätten - und das nicht nur, weil Politik zwangsläufig alle Lebensbereiche durchdringt. Kirchen sind immer politisch positioniert. Die Kirchen des Kaiserreichs lehrten statt der Subversion, die Fleischhauer mißfällt, eben Ruhe, Gehorsam und Ordnung als Christenpflicht und halfen damit dem status quo in Deutschland. Luther verfaßte neben der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen auch An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation und griff damit religiös-politische Zustände an. Eine Art politische Neutralität der Kirche ist nur durch Staatsterror zu erreichen.

Zweitens ist die Trennung zwischen "Religion" und "Politik" fiktiv. Es gibt keine religiöse Sphäre, in der es nur um Engelein und Abendmahl ginge, die Gesellschaft insgesamt aber fein säuberlich außen vor bliebe. In der Gottesherrschaft des Alten Testaments ist das unübersehbar, aber auch das Evangelium ist zutiefst politisch. Die Werte, die Gläubige ihrer Religion entnehmen, beeinflussen ihr politisches Engagement, und die Gesellschaftskonstellation durchdringt umgekehrt die Kirche. Die scheinbare Trennung von Religion und Politik, Staat und Kirche ist dafür sogar das beste Beispiel, denn sie ist das unmittelbare Produkt der kapitalistischen gesellschaftlichen Revolution (wozu siehe Marx, Zur Judenfrage).

Stimmt es nun, daß "[k]aum ein Pastor [sich noch] traut..., ungeniert von Himmel und Hölle zu sprechen"? Damit hat Fleischhauer in meiner Erfahrung allerdings recht. Und wenn die Kirche also zur Gruppentherapie und Ethikstunde verkommt, in der man sich der Bibel schämt, wie vielerorts geschehen, macht sie sich tatsächlich selbst überflüssig. Aber daraus läßt sich keineswegs schließen, daß die Kirche gesellschaftliches Engagement aufgeben und nur noch von Kreuzigung und Höllenfeuer zu erzählen hätte. Ein solcher Rückzug wäre wie schon gesagt ohnehin unmöglich. Vielmehr gibt das Evangelium der Kirche eine einzigartige Perspektive auf gesellschaftliche Fragen und kann einen Dialog zwischen Gott und Welt anstoßen, der beide bereichert.

Jesus' Spruch, wonach ein Kamel leichter durch ein Nadelöhr als ein Reicher ins Himmelreich gehe, ist wenig tröstlich für die Herrschaft. Jesaja 58 zerlegt die zurschaugestellte Frömmigkeit jener Elite, die zugleich die Armen auspreßt. Das Evangelium - daß alle Menschen in ihrem Wert, aber auch ihrer Schuld vor Gott gleich sind und Christus als Mensch lebte, hungerte, litt und für uns starb - gehört keineswegs jenen, die aus ihm Akzeptanz der Gesellschaftsordnung ablesen wollen. Vielmehr leitet es zur Kritik an. Diese Kritik - den Dialog zwischen Wort und Welt - kann die Kirche führen. Daß sie sich in Dresden in die großen Gesellschaftsfragen einmischt, ist gut für die Kirche und gut für die Gesellschaft.

Labels:

Christianity,

deutsch,

economics,

historical materialism,

religion,

socialism

Monday, 2 May 2011

Why we shouldn't celebrate Osama's death

At 1am on May 2, 2011, Osama bin Laden was attacked at his compound in Pakistan by 20 to 25 helicopter-borne Navy SEALs. In a forty-minute operation Osama was shot in the face twice, killing him. The body was quickly dropped into the Arabian Sea.

The reaction in the West was euphoric. Celebrations broke out in the United States. The media were hardly more reticent and celebrated anything from the end of the 'War on Terror' to Obama's now allegedly guaranteed re-election. Osama bin Laden, that incarnation of evil, was finally gone.

I feel personally deeply uncomfortable with the cheering on of the targeted killing of a human being - any human being. At the risk of preaching: breaking forth in joy should never be our reaction to death. That we live in a world in which it may sometimes be necessary to kill other human beings is a terrible fact, one that ought to occasion a fundamental critique of the way we live on this earth. Joy at death is never justified, merely a symptom of our sickness. To gloat over the bodies of our dead enemies, of someone who has been hunted for years, is the opposite of humanity. Osama bin Laden, like Saddam Hussein before him, has been hounded to his grave and beyond, and that should lead to some deep soul-searching in a society that professes to be civilised.

That much is, I hope, uncontroversial; controversy follows. Osama bin Laden was not a demon, not evil incarnate. Fighting him was not some sort of historic challenge the West had to pass. He was a human being with hopes, dreams, fears and aspirations. His millennial outlook stemmed from an understanding of the history of the Middle East - specifically, the history of Western imperialism in the region. As he said in 2004, in the video address in which he first admitted to planning the 9/11 attacks:

So here's my second reason for rejecting the joy at Osama bin Laden's death: it is another act of silencing the voices crying out in protest against the violent and continued suppression of the people of the Middle East. Osama bin Laden was never worthy of our respect. He was a ruthless mass murderer, but he became so in reaction to real injustices. We should feel uneasy about joining in the celebrations when the world's greatest power - the power that turned Iraq into a graveyard and even now aids in the suppression of pro-democracy uprisings in the region - kills one of its enemies. Osama was never a threat to 'the world'. Throughout the 'War on Terror' Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida were always the weaker party, hunted with the most modern weaponry. al-Qaida's weakening was always the likely outcome.

There is, however, hope in all this. As al-Qaida is becoming less relevant, the Middle East is being overtaken by democratic uprisings. Terrorism was the political and military expression of Middle Easterners' impotence and oppressed state; Tahrir Square is the expression of their coming to freedom - real popular freedom, not 'governance' at gunpoint, almost everywhere in defiance of the United States' wishes. It is good that Jihadism is taking a back seat; it is better that democracy has a chance of taking its place.

The reaction in the West was euphoric. Celebrations broke out in the United States. The media were hardly more reticent and celebrated anything from the end of the 'War on Terror' to Obama's now allegedly guaranteed re-election. Osama bin Laden, that incarnation of evil, was finally gone.

I feel personally deeply uncomfortable with the cheering on of the targeted killing of a human being - any human being. At the risk of preaching: breaking forth in joy should never be our reaction to death. That we live in a world in which it may sometimes be necessary to kill other human beings is a terrible fact, one that ought to occasion a fundamental critique of the way we live on this earth. Joy at death is never justified, merely a symptom of our sickness. To gloat over the bodies of our dead enemies, of someone who has been hunted for years, is the opposite of humanity. Osama bin Laden, like Saddam Hussein before him, has been hounded to his grave and beyond, and that should lead to some deep soul-searching in a society that professes to be civilised.

That much is, I hope, uncontroversial; controversy follows. Osama bin Laden was not a demon, not evil incarnate. Fighting him was not some sort of historic challenge the West had to pass. He was a human being with hopes, dreams, fears and aspirations. His millennial outlook stemmed from an understanding of the history of the Middle East - specifically, the history of Western imperialism in the region. As he said in 2004, in the video address in which he first admitted to planning the 9/11 attacks:

Security is an important foundation of human life and free people do not squander their security, contrary to Bush's claims that we hate freedom. Let him tell us why we did not attack Sweden for example...

God knows it did not cross our minds to attack the towers but after the situation became unbearable and we witnessed the injustice and tyranny of the American-Israeli alliance against our people in Palestine and Lebanon, I thought about it. And the events that affected me directly were that of 1982 and the events that followed - when America allowed the Israelis to invade Lebanon, helped by the US sixth fleet.

In those difficult moments many emotions came over me which are hard to describe, but which produced an overwhelming feeling to reject injustice and a strong determination to punish the unjust.

As I watched the destroyed towers in Lebanon, it occurred to me punish the unjust the same way [and] to destroy towers in America so it could taste some of what we are tasting and to stop killing our children and women.

Of course this is propaganda. But at its bottom is undoubtedly a real situation: namely, the Western partition of the Middle East that followed the First World War ('Our Islamic nation has been tasting the same for more than 80 years of humiliation and disgrace, its sons killed and their blood spilled, its sanctities desecrated', Osama said in 2001), and the sordid history of imperialism (first predominantly British, then chiefly American) that continues to this day. Osama's analysis is flawed: he assumes imperialism constitutes a 'crusading' assault on Islam, when it is really a question of economic interests and strategic paramountcy. From this incorrect analysis stems the viciousness and futility of al-Qaida's struggle. That real Western domination and subjugation of Muslims lay at the bottom of the Jihadist attacks was of course never acknowledged by the United States and its allies, who preferred to ascribe their enemies' determination to blind fanaticism. All this, of course, while massively adding to the grievances with the hundreds of thousands killed and millions displaced from Iraq, Afghanistan and other countries.

So here's my second reason for rejecting the joy at Osama bin Laden's death: it is another act of silencing the voices crying out in protest against the violent and continued suppression of the people of the Middle East. Osama bin Laden was never worthy of our respect. He was a ruthless mass murderer, but he became so in reaction to real injustices. We should feel uneasy about joining in the celebrations when the world's greatest power - the power that turned Iraq into a graveyard and even now aids in the suppression of pro-democracy uprisings in the region - kills one of its enemies. Osama was never a threat to 'the world'. Throughout the 'War on Terror' Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida were always the weaker party, hunted with the most modern weaponry. al-Qaida's weakening was always the likely outcome.

There is, however, hope in all this. As al-Qaida is becoming less relevant, the Middle East is being overtaken by democratic uprisings. Terrorism was the political and military expression of Middle Easterners' impotence and oppressed state; Tahrir Square is the expression of their coming to freedom - real popular freedom, not 'governance' at gunpoint, almost everywhere in defiance of the United States' wishes. It is good that Jihadism is taking a back seat; it is better that democracy has a chance of taking its place.

Labels:

economics,

history,

Islam,

Middle East,

religion

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)