Back in the day I enjoyed A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge (1985), but the reviews I've read since haven't been kind. And yet the film really holds up. Freddy's Revenge has problems, sure; a lot of them if you're exacting, but none to my mind film-breaking. And at the same time it's really bold and experimental and subversive (within the limits of the extremely rigid slasher genre, you understand). That's partly by accident - slasher aficionados have given the genre far more thought than the people who made most of these films ever did - but it's real nonetheless.

We open on a school bus in Springwood, Ohio, where an awkward-looking teenage boy, Jesse (Mark Patton) sits alone, while groups of cool kids giggle among themselves. But what seems like a normal ride to school turns to terror when the bus driver, a burnt-looking man with a knife-glove, drives the bus off the road and into the desert (!?), where shenanigans ensue - until Jesse wakes up, soaked in sweat and screaming, in his bed.

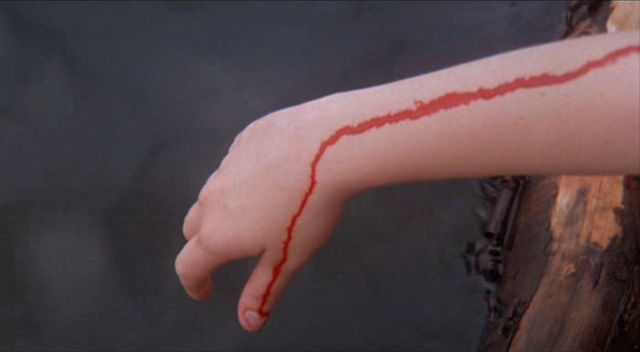

It turns out that awful nightmares have been a regular feature of Jesse's life since his family moved to 1428 Elm Street, the house where Nancy Thompson lived in the first film. Jesse has trouble fitting in at school, spending time only with his girlfriend, Lisa (Kim Myers). The nightmares grow worse: Jesse finds himself walking into the boiler room in the basement and keeps running into the fedora-clad bus driver from his nightmares, one Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund). Freddy explains that he wants Jesse to 'kill for him' so that he can take over his body and return to the real world. Before long the bodies start to pile up, each followed by Jesse waking up with Freddy's glove on his hand...

The plot isn't just not a rehash of the original, it inverts it: where in A Nightmare on Elm Street Nancy was trying to pull Freddy into the real world to defeat him, in Freddy's Revenge it's Freddy himself who's trying to punch through the looking glass, while the heroes are trying to keep him down. What I like best, though (SPOILERS), is that the role of protagonist shifts from Jesse to Lisa at the end of the second act. As Jesse becomes ever more stressed and sleep-deprived, he's increasingly incapable of dealing with the situation; eventually, Freddy takes over his body entirely, so that Jesse, inasmuch as he exists any more, is now the antagonist. Lisa takes over as Final Girl and resolves the plot, so that the happy ending is her freeing him from captivity. The standard slasher structure is definitely there, but twisted for a more interesting take.

Here's what makes this messier, alas: Freddy's Revenge doesn't follow the franchise rulebook for what Freddy can and can't do. While he's still yelling about how he wants to return to the real world, he's already doing things in the real world that he shouldn't be able to. Specifically, a lot of stupid poltergeist crap that's more baffling than scary, like setting the family toaster on fire ('It wasn't even plugged in!' dunh dunh dunh) or the film's abiding moment of shame: Freddy possessing the family parakeet. Oh noes, the bird is swooping down on the family in tremendously goofy POV angles, giving Jesse's dad a minor cut on the cheek! Shock horror, Jesse's dad broke the lamp trying to hit the bird! Followed by the pièce de résistance: the bird bursts into flames and blows up, showering the family with feathers, like it swallowed a stick of dynamite in a forties cartoon.

But then again, A Nightmare on Elm Street didn't do it by the book either: Freddy levitates Tina off the bed, in one of that film's best scenes, in a way he absolutely shouldn't be able to do according to what we think of as the franchise rules. The ending, of course, is famously obscure and totally blurs the line between dream and real world: you tell me who's alive and who's dead at the end of the first film, since I can't (Freddy's Revenge clears that up in a bit of exposition), whether Glen and Nancy's mum were in fact dragged off bodily to the underworld or not and so on. Really, Freddy's Revenge is breaking rules that didn't exist yet when it was made, so I'm happy to give it a pass.

Then there's the issue of what, if you didn't know the meaning of words, you might call the film's 'homoerotic subtext'. Jesse is gay. It's just barely possible to read the film in other ways, since no-one ever says so in so many words; but really everything that's right there in the finished product insists on it. A small part of this is only due to Patton's performance (his palpable discomfort at Lisa's attempts at seduction, for instance), but pace writer David Chaskin, Jesse's visit to a fetish club or Coach Schneider's naked shower death are all in the writing and pretty hard to misinterpret. What's more, this can't be separated from the plot. Jesse's uncertainty about his own identity and inability to open up to his girlfriend create the insecurity that makes him a perfect victim for Freddy. 'The gay issue' isn't extraneous, it's central to the plot.

The dream sequences are much better than I remembered, though not a patch on Dream Warriors; the performances are fine, i.e. not Heather Langenkamp, but not Friday the 13th Expendable Meat either. Freddy is still a skulking shadow-dweller, but he does talk more this time around, since he has to explain the plot. He's definitely not yet the killer clown he'd later become, though. Witness this exchange towards the end of the film:

TERRIFIED PARTYGOER: Just tell us what you want, all right? I'm here to help you. FREDDY: Help yourself, fucker! *kills him*Not exactly a zinger, is it?

Dream Warriors would bring back Heather Langenkamp and take the franchise in a totally different, initially delightful direction. That means Freddy's Revenge is a dead end, a road not taken. Does it have flaws? Yes, definitely. But it's still very much worth it: besides being a decent way to spend an hour and a half, it's one of the strangest slashers of the eighties.

_theatrical_poster.jpg)