The Empire Strikes Back (1980) started a Star Wars tradition of confusing and alienating audiences that has become pretty much synonymous with the franchise over the years. For despite being advertised by just that four-word title ahead of release (see the poster), the film's opening crawl instead referred to it as Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back. A science-fiction franchise had suddenly become a humongous 'saga' that had apparently and inexplicably begun on its fourth installment. The course had been set for a bright future of crippling continuity errors and, eventually, a leaden prequel trilogy - a curious achievement for what is clearly and unequivocally the best film in the series.

This doesn't quite seem to have been the intention right at the start: some of the most distinctive plot elements of Empire (SPOILERS) were only introduced by George Lucas after he was disappointed by a first draft, written by veteran space opera and planetary romance writer Leigh Brackett in the final stages of her battle with cancer. In reworking the script Lucas came up with the film's darker direction and the no-longer-stunning plot twist that Darth Vader is (well, claims to be, as far as Empire is concerned) Luke Skywalker's father. This in turn led to a backstory expansion in which Anakin Skywalker was Obi-Wan Kenobi's apprentice before being seduced by the Emperor (now a user of the dark side of the Force and no longer a mere politician, though not yet Ian McDiarmid), opening the possibility of a prequel trilogy. This newer, bigger story also retroactively turned Obi-Wan into a liar who manipulated Luke into helping him and attempting to blow up his own father along with the Death Star, but really, in the continuity mess of even the core Star Wars canon that's small change.

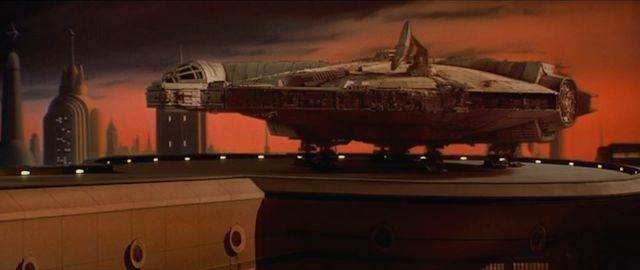

The story: forces of the Rebel Alliance, including all the surviving

heroes of the previous film, have constructed a base on the inhospitable

ice world of Hoth. Before long, though, they're discovered by the

Imperial fleet of Darth Vader. The rebels manage to hold off the

Imperial ground assault long enough to pull off a successful withdrawal

but Han Solo and Leia Organa (Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher) fail to

get away from the Imperials because of the Millennium Falcon's broken

hyperdrive. Hiding first in a deadly asteroid field and then fleeing to

Cloud City, where Han's old frenemy Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee

Williams) runs a mining operation, they're hunted by Vader's fleet as

well as a bunch of bounty hunters.

Meanwhile, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) follows a vision of his one-time mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi to the swamp world of Dagobah. There, Obi-Wan's own teacher, the diminutive and ancient Jedi master Yoda (Frank Oz), instructs him in the ways of the Force, teaching him to become a Jedi knight himself. Before he can complete his training, though, Luke has a premonition of his friends in danger. Worried by Yoda's warnings but ultimately unable to ignore Han and Leia's suffering, Luke races off to Cloud City, his training unfinished, to save his friends from Vader's clutches.

The final script, written by Lawrence Kasdan based on Lucas's second

draft, is fantastic: it zips by, the necessary exposition is handled

supremely well (for a film that expands the story so much, there are

very few scenes of character simply sitting down and talking), and the

dialogue is much punchier and more contemporary than Lucas's

self-conscious throwback pulp stylings in Star Wars. Those work too, and having lavished praise on Lucas's script I'm not about to change my mind. But what worked for Star Wars wouldn't work for Empire:

where the first film was all about roughly sketching a world of

intergalactic adventure and a stark battle between good and evil, the

second installment fleshes out that world and develops its characters

from old-school sci-fi archetypes into, well, people.

(Even so, let's not beat about the bush: the timeline of Empire is pretty much impossible (which isn't to say Star Wars

fans haven't made up elaborate excuses for the film). In the time that

Han and Leia take to run from Hoth to Bespin, the Empire hot on their

heels (a few standard days at most), Luke goes to Dagobah, meets Yoda

and gets a significant chunk of Jedi training done (weeks at least).

Impossible in terms of realism, to be sure. But in story terms, it

works: Luke's less action-packed, more contemplative and philosophical

scenes alternate effectively with scenes of danger involving Han and

Leia. Time has always moved at the speed of plot in Star Wars, and I'm

happy to give the film a pass here.)

The new and improved dialogue does a lot for the characters, and it's a much better fit for some of the actors. Carrie Fisher's Leia is even more acerbic this time around, and Kasdan gives her a couple of fantastic zingers: 'Would it help if I got out and pushed?' when Han's rust bucket won't get going, or the wondrous 'You don't have to do this to impress me' as he heads into an asteroid field. That brings us neatly to the problem of Leia in Empire: she's reduced from the aristocratic leader of Star Wars to playing the straight man to Han Solo's antics. Which is enjoyable, but leaves the character a little thin. Ford is freer and looser this time around (thanks, no doubt, to a more cooperative director), and Hamill is - well, I like him less in Empire than in either Star Wars or Jedi, but his final scenes in the film are terrific, no doubt about it.

In the smaller roles there's so much goodness: I'm a particular fan of

all the pitiable Imperial officers who must achieve impossible

objectives, or be murdered by Vader. (There is, in general, a lot of

excellent bleak humour in the scenes aboard the Executor). An

easy favourite is Kenneth Colley's put-upon Admiral Piett, a man who

through long practice has become really good at ignoring people being

force-choked right next to him, and actually makes it out of Empire alive.

But Julian Glover's General Veers, a man who clearly enjoys nothing

more than (a) sneering and (b) stomping on infantry with his enormous

armoured tank, is a wonderful mini-villain too. On the other side, I'm a

big fan of Bruce Boa's General Rieekan, who radiates a slightly gruff

but likeable authority on Hoth.

That's all well and good, but let's get to the best character in Empire, shall we? Because Yoda is that. I still love the reveal that the cackling imp who rummages through Luke's equipment is, in fact, a powerful Jedi master. He's a perfect embodiment of the film's thesis that the Force as a mystical ally can help the weak triumph over the strong, that it makes the underdog's victory over all the Empire's might a real possibility. He injects a warm sense of wonder about the Force, a humanist love of people over cold military power ('luminous beings are we, not this crude matter') and a yearning for peace ('wars not make one great'). And he does it all with humour (Frank Oz's outraged delivery of 'Mudhole? Slimy? My home this is!' cracks me up every time), dignity, and real authority. I understand that for Hamill weeks of sharing the scene with a puppet weren't too much fun, but the result is spellbinding.

(You know who sucks in Empire, though? Obi-Wan Kenobi. He does nothing but deliver some exposition and whinge about stuff. And Alec McGuinness, whose wry self-amusement worked wonders in Star Wars, is really phoning it in this time around. It's a waste.)

Lucas didn't do much to polish Empire in the special editions and home video releases. The major exception - one Star Wars fans don't object to, curiously - is Ian McDiarmid portraying the emperor (instead of Elaine Baker with digitally inserted chimpanzee eyes and Clive Revill doing the voice). Even better is that you don't need the despecialized edition to appreciate the special effects, which Lucas, despite his reputation, has only ever tweaked to remove errors. And they're wonderful. Terrifying stop-motion AT-ATs marching mercilessly across the frozen landscape while seemingly mosquito-sized rebel snowspeeders flit around them, a city floating above the clouds, a star destroyer adrift after a hit from the ion cannon. My absolute favourite, though, is the tauntauns. The puppet work in close-ups is very good, but I adore the stop-motion used in wide shots even more. The creatures move in an alien yet believable way, and they've got an almost Harryhausenesque amount of personality. (Plus great sound design, but in Star Wars that goes without saying.)

In the hands of Irvin Kershner Empire is a bit more life-sized than Star Wars, its characters just as mythical but a little less archetypal. By the second film, the series was starting to fill out its world, developing its characters (who are starting to feel like people we know and like instead of The Naive Young Hero, The Rogue, The Damsel, The Mentor, &c.) and breaking free from its '30s forebears. Put another way, Empire feels much less like Flash Gordon fan-fiction and much more like the work of people who suspected that more than just paying homage to them, Star Wars would utterly displace the pulp serials of yore in the public imagination. With a compelling story involving great characters, terrific setpieces and top-notch craftsmanship, Empire provides a good argument that Star Wars' place as a pop culture juggernaut is fully and legitimately earned.

Showing posts with label science fiction. Show all posts

Showing posts with label science fiction. Show all posts

Wednesday, 18 November 2015

Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter

Saturday, 3 October 2015

Hokey religions and ancient weapons

Star Wars is the first blockbuster franchise I loved. Whether it was for lack of interest or because I preferred books, I didn't watch a lot of films when I was a kid. Star Wars blew me away. It opened up my imagination to a whole world of pulp science fantasy and started me off on a geeky obsession that has never gone away, attested to by shelves of tattered, treasured Expanded Universe novels.

Admittedly the Star Wars film I'm talking about was The Phantom Menace, and I only caught up with the first film in the series on VHS a few months later. I loved them both - I suppose I wasn't the most discriminating eleven-year-old. With time I learnt that fandom orthodoxy frowned on The Phantom Menace but loved Episode IV: A New Hope, as Lucas retitled the 1977 film on its re-release. And at least as far as Episode IV is concerned, the fandom is right. The film is ace: a total matinee delight that may not be the same technical marvel it appeared in 1977, but holds up just about perfectly all the same.

(A quick note: the basis for this review is the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars, a fan-made high-definition version of the original trilogy that attempts to restore the films as they originally appeared in cinemas, instead of the 1997 'special editions' (plus subsequent additions and changes) that modern Blu-ray copies are based on - fan-made because Lucas infamously wouldn't release anything except his new and allegedly improved versions in high-definition.

The thing is, the special editions are how I first experienced Star Wars, and I imagine it's the same for a lot of people who weren't around in the seventies and early eighties. But because of all the criticism the special editions get in fan circles - Han shot first et cetera ad nauseam - I was aware of most of the changes. They're pretty minor, by and large: CGI critters instead of practical effects, mostly, and a weird floating Jabba who pops in to utter the exact same threats Greedo did hardly five minutes earlier. But there's one exception: a scene near the end, in which Luke meets his old Tattooine mate Biggs Darklighter on Yavin 4, which ended up on the cutting room floor in the original release but was restored for the special editions. And considering the banter between the pilots during the Death Star attack is damn weird without that scene - they're talking as if they've known each other all their lives, which isn't indicated in anything we've seen before - restoring it was clearly the right decision.)

The story: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a nineteen-year-old living on the backwater planet of Tatooine, longs to be released from his tedious life on his uncle's moisture farm and go off to become a starfighter pilot. Tasked with cleaning two new droids his uncle has bought (Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker), Luke discovers they're carrying a message of vital importance from Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), which they're tasked with relaying to a retired general and current hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that just like himself, Luke's father was a Jedi Knight, a fighter for good drawing on the mystical Force killed by the evil Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), and perhaps Luke would like to accompany him to leave Tatooine and join Princess Leia in their rebellion against the evil Galactic Empire?

This is understandably too much for Luke to take in straight away, but his decision is made for him: Imperial stormtroopers attack his home, massacring his aunt and uncle and forcing Luke, Obi-Wan and the droids to flee. In the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, they hire smuggler Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his towering alien sidekick Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), who are themselves in a lot of trouble with some unsavoury elements. Together, this motley crew head to Leia's homeworld of Alderaan, only to find the whole planet obliterated by something that decidedly isn't any moon...

Everyone knows that story, but it's perhaps worth pointing out the ways in which the plot of the 1977 film isn't the story of the Star Wars franchise that developed after it, simply because George Lucas and his collaborators hadn't settled on those things yet. Certain family relationships don't yet exist; Obi-Wan unambiguously hates Vader's guts; the Jedi are treated as a myth of the ancient past and the existence of the Force is explicitly denied by several characters, although in the course of the film it seems to become the official creed of the Rebel Alliance; the emperor is a distant, unseen figure; Vader is only one of the empire's henchmen and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) orders him around, while others openly insult his religious beliefs.

It's so simple and archetypal (little wonder, since Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces): a wide-eyed audience stand-in who dreams of seeing something of the world, be a hero and rescue a beautiful princess; a wise old mentor, not long for this world; a charming rogue who learns to value friendship over money; a dastardly villain; and a character who, yes, is at this point still kind of an old-school damsel in distress, but at least has her own mind, some justifiable complaints about her ill-planned rescue, and ideas for how to do a better job. But it takes skill to do this stuff well, and Star Wars does it extremely well.

The script isn't usually given the amount of credit it's due, but it's among the reasons for the success of Star Wars and its immediate ability to capture the imagination. Lucas wrote the thing more than once, never happy with the results, and when Star Wars started filming in Tunisia the screenplay was still unfinished. The process of often sharply critical feedback over several years from Hollywood insiders and Lucas's wife, as well as uncredited dialogue rewrites by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, somehow produced a particular alchemy.

The result is glorious high pulp, instantly quotable and wonderful: "You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy"; "I find your lack of faith disturbing"; "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid"; "Evacuate? In our moment of triumph?"; "The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers", and so on. None of this is remotely how real people talk, but it gives the film an outsized air of adventure and wonder that helps it hit all the high notes.

Then there are the performances. The role of Luke Skywalker at this point is still something of a generic person, but Mark Hamill gets that right: we like and empathise with Luke, and that's what the film needs. The others are allowed to do more, and they're terrific. Alec Guinness forever seems gently amused at being asked to deliver dialogue about Jedi knights and disturbances in the Force, which results in a winning, light performance. Peter Cushing, veteran Hammer Horror vampire hunter, makes for a marvellously icy and authoritative warlord with drive, determination and cruelty to spare.

To me, there are three standouts: Harrison Ford's natural charisma causes him to make the role his own so much that he essentially spun it off into another franchise, as Indiana Jones. Anthony Daniels portrays C-3PO as a self-pitying but fundamentally decent comic foil who gets some of the film's biggest laughs ("Listen to them, they're dying, R2! Curse my metal body, I wasn't fast enough, it's all my fault!") And lastly, David Prowse's physical acting has always been overshadowed by James Earl Jones's voice, but his performance inside the Darth Vader suit is perfect: authoritative and menacing, but very far from emotionless. I adore the scene in which he pauses as he senses Obi-Wan for the first time; it's subtle but all kinds of wonderful.

Star Wars wouldn't be Star Wars without the lovely production design, though: it's chock-full of amazing ideas brilliantly executed. And unlike the second and third prequels, which are full of stuff happening in the background, the first film has the sense to actually briefly focus on the terrific alien suits, grime-covered droids and fossils bleached by the Tatooine suns, giving them each the dignity and two seconds of glory they deserve. (My favourite is and remains the tiny droid skittering away from Chewbacca on the Death Star, beeping in fear.) The film's used-future aesthetic - which belongs exclusively to the good and neutral characters, while the Empire is exquisitely glossy - is wonderfully and consistently realised.

The special effects are extremely good: they look dated, yes, but virtually never unconvincing. The real star is Ben Burtt's sound design, though. From all the mechanical whirring and hissing to Chewbacca's voice and Vader's breathing, the sounds of Star Wars remain instantly recognisable. There's so much high-class craftsmanship here, it really makes you appreciate the often-forgotten art of sound design (and miss it in all the projects that neglect to go beyond mere competence).

So what doesn't hold up? Despite everything, the final film is a bit slight; it zips past having established fairly little of its world beyond rough outlines, and selling some of its character development more through conviction than storytelling logic (Luke's attachment to Obi-Wan, in particular, feels dodgy after so short an acquaintance, especially since he immediately forgets about the people who raised him). The film offers a world of adventure so appealing, it's not surprising people wanted sequels and an enormous expanded universe. But it also feels a little like Star Wars needed those things to round it out, and like, had nothing else ever followed, the film would feel roughly sketched. But if the worst thing I can say about a film is that I want more of its world and characters than it can possibly provide in two hours, well...

Admittedly the Star Wars film I'm talking about was The Phantom Menace, and I only caught up with the first film in the series on VHS a few months later. I loved them both - I suppose I wasn't the most discriminating eleven-year-old. With time I learnt that fandom orthodoxy frowned on The Phantom Menace but loved Episode IV: A New Hope, as Lucas retitled the 1977 film on its re-release. And at least as far as Episode IV is concerned, the fandom is right. The film is ace: a total matinee delight that may not be the same technical marvel it appeared in 1977, but holds up just about perfectly all the same.

(A quick note: the basis for this review is the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars, a fan-made high-definition version of the original trilogy that attempts to restore the films as they originally appeared in cinemas, instead of the 1997 'special editions' (plus subsequent additions and changes) that modern Blu-ray copies are based on - fan-made because Lucas infamously wouldn't release anything except his new and allegedly improved versions in high-definition.

The thing is, the special editions are how I first experienced Star Wars, and I imagine it's the same for a lot of people who weren't around in the seventies and early eighties. But because of all the criticism the special editions get in fan circles - Han shot first et cetera ad nauseam - I was aware of most of the changes. They're pretty minor, by and large: CGI critters instead of practical effects, mostly, and a weird floating Jabba who pops in to utter the exact same threats Greedo did hardly five minutes earlier. But there's one exception: a scene near the end, in which Luke meets his old Tattooine mate Biggs Darklighter on Yavin 4, which ended up on the cutting room floor in the original release but was restored for the special editions. And considering the banter between the pilots during the Death Star attack is damn weird without that scene - they're talking as if they've known each other all their lives, which isn't indicated in anything we've seen before - restoring it was clearly the right decision.)

The story: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a nineteen-year-old living on the backwater planet of Tatooine, longs to be released from his tedious life on his uncle's moisture farm and go off to become a starfighter pilot. Tasked with cleaning two new droids his uncle has bought (Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker), Luke discovers they're carrying a message of vital importance from Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), which they're tasked with relaying to a retired general and current hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that just like himself, Luke's father was a Jedi Knight, a fighter for good drawing on the mystical Force killed by the evil Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), and perhaps Luke would like to accompany him to leave Tatooine and join Princess Leia in their rebellion against the evil Galactic Empire?

This is understandably too much for Luke to take in straight away, but his decision is made for him: Imperial stormtroopers attack his home, massacring his aunt and uncle and forcing Luke, Obi-Wan and the droids to flee. In the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, they hire smuggler Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his towering alien sidekick Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), who are themselves in a lot of trouble with some unsavoury elements. Together, this motley crew head to Leia's homeworld of Alderaan, only to find the whole planet obliterated by something that decidedly isn't any moon...

Everyone knows that story, but it's perhaps worth pointing out the ways in which the plot of the 1977 film isn't the story of the Star Wars franchise that developed after it, simply because George Lucas and his collaborators hadn't settled on those things yet. Certain family relationships don't yet exist; Obi-Wan unambiguously hates Vader's guts; the Jedi are treated as a myth of the ancient past and the existence of the Force is explicitly denied by several characters, although in the course of the film it seems to become the official creed of the Rebel Alliance; the emperor is a distant, unseen figure; Vader is only one of the empire's henchmen and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) orders him around, while others openly insult his religious beliefs.

It's so simple and archetypal (little wonder, since Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces): a wide-eyed audience stand-in who dreams of seeing something of the world, be a hero and rescue a beautiful princess; a wise old mentor, not long for this world; a charming rogue who learns to value friendship over money; a dastardly villain; and a character who, yes, is at this point still kind of an old-school damsel in distress, but at least has her own mind, some justifiable complaints about her ill-planned rescue, and ideas for how to do a better job. But it takes skill to do this stuff well, and Star Wars does it extremely well.

The script isn't usually given the amount of credit it's due, but it's among the reasons for the success of Star Wars and its immediate ability to capture the imagination. Lucas wrote the thing more than once, never happy with the results, and when Star Wars started filming in Tunisia the screenplay was still unfinished. The process of often sharply critical feedback over several years from Hollywood insiders and Lucas's wife, as well as uncredited dialogue rewrites by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, somehow produced a particular alchemy.

The result is glorious high pulp, instantly quotable and wonderful: "You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy"; "I find your lack of faith disturbing"; "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid"; "Evacuate? In our moment of triumph?"; "The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers", and so on. None of this is remotely how real people talk, but it gives the film an outsized air of adventure and wonder that helps it hit all the high notes.

Then there are the performances. The role of Luke Skywalker at this point is still something of a generic person, but Mark Hamill gets that right: we like and empathise with Luke, and that's what the film needs. The others are allowed to do more, and they're terrific. Alec Guinness forever seems gently amused at being asked to deliver dialogue about Jedi knights and disturbances in the Force, which results in a winning, light performance. Peter Cushing, veteran Hammer Horror vampire hunter, makes for a marvellously icy and authoritative warlord with drive, determination and cruelty to spare.

To me, there are three standouts: Harrison Ford's natural charisma causes him to make the role his own so much that he essentially spun it off into another franchise, as Indiana Jones. Anthony Daniels portrays C-3PO as a self-pitying but fundamentally decent comic foil who gets some of the film's biggest laughs ("Listen to them, they're dying, R2! Curse my metal body, I wasn't fast enough, it's all my fault!") And lastly, David Prowse's physical acting has always been overshadowed by James Earl Jones's voice, but his performance inside the Darth Vader suit is perfect: authoritative and menacing, but very far from emotionless. I adore the scene in which he pauses as he senses Obi-Wan for the first time; it's subtle but all kinds of wonderful.

Star Wars wouldn't be Star Wars without the lovely production design, though: it's chock-full of amazing ideas brilliantly executed. And unlike the second and third prequels, which are full of stuff happening in the background, the first film has the sense to actually briefly focus on the terrific alien suits, grime-covered droids and fossils bleached by the Tatooine suns, giving them each the dignity and two seconds of glory they deserve. (My favourite is and remains the tiny droid skittering away from Chewbacca on the Death Star, beeping in fear.) The film's used-future aesthetic - which belongs exclusively to the good and neutral characters, while the Empire is exquisitely glossy - is wonderfully and consistently realised.

The special effects are extremely good: they look dated, yes, but virtually never unconvincing. The real star is Ben Burtt's sound design, though. From all the mechanical whirring and hissing to Chewbacca's voice and Vader's breathing, the sounds of Star Wars remain instantly recognisable. There's so much high-class craftsmanship here, it really makes you appreciate the often-forgotten art of sound design (and miss it in all the projects that neglect to go beyond mere competence).

So what doesn't hold up? Despite everything, the final film is a bit slight; it zips past having established fairly little of its world beyond rough outlines, and selling some of its character development more through conviction than storytelling logic (Luke's attachment to Obi-Wan, in particular, feels dodgy after so short an acquaintance, especially since he immediately forgets about the people who raised him). The film offers a world of adventure so appealing, it's not surprising people wanted sequels and an enormous expanded universe. But it also feels a little like Star Wars needed those things to round it out, and like, had nothing else ever followed, the film would feel roughly sketched. But if the worst thing I can say about a film is that I want more of its world and characters than it can possibly provide in two hours, well...

Saturday, 29 September 2012

Gaze into the fist of Dredd

Dredd is the best comic book adaptation of the year. Where The Avengers was a crowd-pleasing something-for-everyone effort and The Dark Knight Rises fumbled its lofty ambitions, Dredd goes its own hyper-authoritarian, gore-soaked way. It's a film that doesn't beg the audience to love it. So far it's grossed just over $19 million worldwide, a pittance next to fellow post-apocalyptic actioner Resident Evil: Retribution's $139 million. That isn't surprising since much of the filmgoing public still associates Judge Dredd with the reviled Sylvester Stallone adaptation, but it's depressing nonetheless.

In the future, war has reduced most of the US to an irradiated wasteland. In Mega-City One, 800 million survivors are crammed into a single urban sprawl stretching from New England to Washington, D.C. As scarcity and the collapse of previous governments have caused a massive crime wave, the city is ruled in an authoritarian fashion and policed by Judges, lawmen entitled to use lethal force and act as judge, jury and executioner.

Judge Dredd (Karl Urban) is assigned a recruit, Cassandra Anderson (Olivia Thirlby). Anderson has failed her exams, but she may be valuable to the Hall of Justice for another reason: as a mutant, she has psychic powers.When the two investigate a seemingly routine triple homicide in a two-hundred-storey apartment block called Peach Trees, they stumble upon the empire of drug kingpin Ma-Ma (Lena Headey). After Ma-Ma shuts down the building to prevent their escape, the Judges must battle their way to the top against hundreds of gangbangers and desperate armed residents.

That's pretty much it. Where lesser comic book films stretch their material to pseudo-epic scope whether it fits the source material or not, there's a lot to be admired in Dredd's single-minded commitment to straightforwardness. Screenwriter Alex Garland (Sunshine) trims all the fat off the story for a lean ninenty-five minute running time. His script does not aspire to do more than chronicle a day's work for Dredd, the equivalent of a four-issue arc in the early 2000AD days, and that simplicity is the film's great strength.

Not that it lacks for strengths. Dredd is a masterclass in distilling the spirit of the comic book without taking on many of its details. The broad characters, physically deformed mutants, robots, laser guns, supernatural creatures and alien planets of the comic books are replaced by a deliberately basic, gritty future world. Technology barely exceeds present-day levels. Ordinary cars and weapons are used by everyone but the better-equipped Judges (and in the course of the film, even Anderson begins carrying an MP-5). The Judges' armour is far simpler and more practical-looking than its comic-book incarnation.

As for the character's heart and soul, Dredd does not attempt to sugarcoat the grimness of the source material. The comic books often overplayed their insanely dark future world for comic effect, but this was lost on quite a few readers. ('To my surprise, and even alarm', Pat Mills muses, 'a psycho character with no feelings would regularly win out any day over a hero who had some humanity or vulnerability.') By contrast, Dredd plays the Dirty-Harry-up-to-eleven concept straight, for a film that pleases everyone's inner authoritarian but troubles the soul. (That is, if satire is not as intrinsic to the concept as I think it is.)

The film is bolstered by three strong central performances. Urban, not allowed to take off his helmet, works his mouth and chin for all they're worth and affects a vocal chord-shredding growl. It sounds silly, but it works. Headey makes the most of the opportunity to exchange her restrained evil of Game of Thrones for unhinged villainy. Thirlby, meanwhile, shoulders the task of audience surrogate and standard 'newbie with a steep learning curve' character, communicating both doubt and increasingly strength effectively.

It's a jolly handsome film that should be seen in 3D. Slo-mo, Ma-Ma's drug that slows time down for the user, is exploited for numerous gorgeous shots of water droplets, explosions - and viciousness. Dredd's many gunfights delight in slow-motion shots of faces torn apart by bullets and other forms of unsavoury violence. Like its titular character, Dredd is single-minded, brutal, and singularly compelling.

In the future, war has reduced most of the US to an irradiated wasteland. In Mega-City One, 800 million survivors are crammed into a single urban sprawl stretching from New England to Washington, D.C. As scarcity and the collapse of previous governments have caused a massive crime wave, the city is ruled in an authoritarian fashion and policed by Judges, lawmen entitled to use lethal force and act as judge, jury and executioner.

Judge Dredd (Karl Urban) is assigned a recruit, Cassandra Anderson (Olivia Thirlby). Anderson has failed her exams, but she may be valuable to the Hall of Justice for another reason: as a mutant, she has psychic powers.When the two investigate a seemingly routine triple homicide in a two-hundred-storey apartment block called Peach Trees, they stumble upon the empire of drug kingpin Ma-Ma (Lena Headey). After Ma-Ma shuts down the building to prevent their escape, the Judges must battle their way to the top against hundreds of gangbangers and desperate armed residents.

That's pretty much it. Where lesser comic book films stretch their material to pseudo-epic scope whether it fits the source material or not, there's a lot to be admired in Dredd's single-minded commitment to straightforwardness. Screenwriter Alex Garland (Sunshine) trims all the fat off the story for a lean ninenty-five minute running time. His script does not aspire to do more than chronicle a day's work for Dredd, the equivalent of a four-issue arc in the early 2000AD days, and that simplicity is the film's great strength.

Not that it lacks for strengths. Dredd is a masterclass in distilling the spirit of the comic book without taking on many of its details. The broad characters, physically deformed mutants, robots, laser guns, supernatural creatures and alien planets of the comic books are replaced by a deliberately basic, gritty future world. Technology barely exceeds present-day levels. Ordinary cars and weapons are used by everyone but the better-equipped Judges (and in the course of the film, even Anderson begins carrying an MP-5). The Judges' armour is far simpler and more practical-looking than its comic-book incarnation.

As for the character's heart and soul, Dredd does not attempt to sugarcoat the grimness of the source material. The comic books often overplayed their insanely dark future world for comic effect, but this was lost on quite a few readers. ('To my surprise, and even alarm', Pat Mills muses, 'a psycho character with no feelings would regularly win out any day over a hero who had some humanity or vulnerability.') By contrast, Dredd plays the Dirty-Harry-up-to-eleven concept straight, for a film that pleases everyone's inner authoritarian but troubles the soul. (That is, if satire is not as intrinsic to the concept as I think it is.)

The film is bolstered by three strong central performances. Urban, not allowed to take off his helmet, works his mouth and chin for all they're worth and affects a vocal chord-shredding growl. It sounds silly, but it works. Headey makes the most of the opportunity to exchange her restrained evil of Game of Thrones for unhinged villainy. Thirlby, meanwhile, shoulders the task of audience surrogate and standard 'newbie with a steep learning curve' character, communicating both doubt and increasingly strength effectively.

It's a jolly handsome film that should be seen in 3D. Slo-mo, Ma-Ma's drug that slows time down for the user, is exploited for numerous gorgeous shots of water droplets, explosions - and viciousness. Dredd's many gunfights delight in slow-motion shots of faces torn apart by bullets and other forms of unsavoury violence. Like its titular character, Dredd is single-minded, brutal, and singularly compelling.

Labels:

action,

after the end,

comic books,

exploitation,

science fiction

Thursday, 13 September 2012

Product Recall

Total Recall is one of those remakes that just are. There was no real reason to dust off Paul Verhoeven's 1990 semi-classic. And yet we have a new Total Recall, apparently inspired by little more than a dim realisation there was money to be made. In that sense the new film, which has proved something of a box office bomb in North America - taking $57.6m to date on a budget of $125m - deserves its fate.

Beyond the fact of its mercenary nature, though, the new Total Recall is about as good as could be expected: uninspired, to be sure, but made with solid craftsmanship. That's thanks mostly to the production design of long-time Roland Emmerich collaborator and Underworld franchise veteran Patrick Tatopoulos, who knows to steal from the best. Its terrific used-future look gives Total Recall the spice the film's bland direction, acting and plotting lack.

Towards the end of the twenty-first century, an opening infodump informs us (I'd say that's a particularly modern sin, but I do believe Escape from New York commits the same transgression, with as little justification), the earth has become largely uninhabitable with the exception of two regions: the United Federation of Britain (UFB), comprising north-western Europe, and Australia, now known as the Colony. In a society where his compatriots are treated as second-class human beings, Colony citizen Douglas Quaid (Colin Farrell) undertakes a daily commute to his assembly-line job by using 'The Fall', a lift that goes straight through the earth's core.

Plagued by dissatisfaction with his life as well as recurrent nightmares, Quaid goes to Rekall, a company that specialises in implanting real-seeming memories. Just as he's being strapped to the chair, though, the place is raided by special forces; Quaid, suddenly using combat skills he never knew he had, makes short work of the intruders. Gradually realising his memory of being an operative of the resistance led by Matthias (Bill Nighy) was wiped, Quaid flees from UFB goons led by his wife, Lori (Kate Beckinsale).

This Total Recall's plot is no more ludicrous than the Verhoeven film's: and yet nonsense set on Mars somehow seems more believable than same happening right here on earth. That said, the transition from space to a terrestrial setting is generally handled well and gives Tatopoulos room to shine. He does so by more or less plagiarising the look of Blade Runner: dark megacities, Oriental cultural artifacts, and a heck of a lot of rain. The sight of English landmarks in a futuristic setting is thoroughly satisfying even as the technology level is disappointing for a film set a century in the future. Unfortunately Total Recall suffers from that bane of recent films, not-quite-there CGI. At times Wiseman's film reaches the plastic unreality of Sucker Punch.

The story beats are more or less the same, excepting an expanded role for Lori, whose presence throughout the film is surely explained more by the fact that Beckinsale is married to the director than by any narrative reason. If anything, Total Recall is hurt by this move, since Beckinsale's character is given no narrative arc whatsoever, leaving the actress stranded with little to do but snarl wickedly and be badass. Which she does with panache, of course. Jessica Biel is saddled with an equally slight character, while Farrell gives the film's most effective performance. His Quaid is far more relatable than Schwarzenegger's ludicrous superman, which is nothing but good in a film in which an ordinary man is thrust into events he cannot understand.

What remains is a sense of weirdness as a slick twenty-first century sci-fi aesthetic delivered by generically beautiful people is grafted onto the gnarled skeleton of a Paul Verhoeven film. Say what you will about Verhoeven, but he was no hack; even in failure his brand of satire, exploitation and gore between the silly and the disturbing was distinctively his own. The result is a film whose 1980s blockbuster subconscious keeps disrupting its modern garb.

Beyond the fact of its mercenary nature, though, the new Total Recall is about as good as could be expected: uninspired, to be sure, but made with solid craftsmanship. That's thanks mostly to the production design of long-time Roland Emmerich collaborator and Underworld franchise veteran Patrick Tatopoulos, who knows to steal from the best. Its terrific used-future look gives Total Recall the spice the film's bland direction, acting and plotting lack.

Towards the end of the twenty-first century, an opening infodump informs us (I'd say that's a particularly modern sin, but I do believe Escape from New York commits the same transgression, with as little justification), the earth has become largely uninhabitable with the exception of two regions: the United Federation of Britain (UFB), comprising north-western Europe, and Australia, now known as the Colony. In a society where his compatriots are treated as second-class human beings, Colony citizen Douglas Quaid (Colin Farrell) undertakes a daily commute to his assembly-line job by using 'The Fall', a lift that goes straight through the earth's core.

Plagued by dissatisfaction with his life as well as recurrent nightmares, Quaid goes to Rekall, a company that specialises in implanting real-seeming memories. Just as he's being strapped to the chair, though, the place is raided by special forces; Quaid, suddenly using combat skills he never knew he had, makes short work of the intruders. Gradually realising his memory of being an operative of the resistance led by Matthias (Bill Nighy) was wiped, Quaid flees from UFB goons led by his wife, Lori (Kate Beckinsale).

This Total Recall's plot is no more ludicrous than the Verhoeven film's: and yet nonsense set on Mars somehow seems more believable than same happening right here on earth. That said, the transition from space to a terrestrial setting is generally handled well and gives Tatopoulos room to shine. He does so by more or less plagiarising the look of Blade Runner: dark megacities, Oriental cultural artifacts, and a heck of a lot of rain. The sight of English landmarks in a futuristic setting is thoroughly satisfying even as the technology level is disappointing for a film set a century in the future. Unfortunately Total Recall suffers from that bane of recent films, not-quite-there CGI. At times Wiseman's film reaches the plastic unreality of Sucker Punch.

The story beats are more or less the same, excepting an expanded role for Lori, whose presence throughout the film is surely explained more by the fact that Beckinsale is married to the director than by any narrative reason. If anything, Total Recall is hurt by this move, since Beckinsale's character is given no narrative arc whatsoever, leaving the actress stranded with little to do but snarl wickedly and be badass. Which she does with panache, of course. Jessica Biel is saddled with an equally slight character, while Farrell gives the film's most effective performance. His Quaid is far more relatable than Schwarzenegger's ludicrous superman, which is nothing but good in a film in which an ordinary man is thrust into events he cannot understand.

What remains is a sense of weirdness as a slick twenty-first century sci-fi aesthetic delivered by generically beautiful people is grafted onto the gnarled skeleton of a Paul Verhoeven film. Say what you will about Verhoeven, but he was no hack; even in failure his brand of satire, exploitation and gore between the silly and the disturbing was distinctively his own. The result is a film whose 1980s blockbuster subconscious keeps disrupting its modern garb.

Labels:

action,

after the end,

cyberpunk,

remake,

science fiction

Monday, 6 February 2012

Viva Bava, Part 6: In space, no-one can hear you make mediocre films

In the early sixties, American International Pictures made a ton of money by distributing Mario Bava's films stateside. They'd usually retitle and edit the original film, removing gore, re-arranging the segments of Black Sabbath and so on. For that reason we Bava aficionados prefer the Italian release versions, but let's give credit where credit is due: without AIP, Bava could never have built a fanbase in America.

Despite having passed on Blood and Black Lace, AIP still wanted to distribute Bava's films, and they decided to get closer to the source. Thus it was that the maestro's next feature was financed jointly by AIP and Francoist Spain's Castilla Cooperativa Cinematográfica, and for the first time a Bava film was released almost simultaneously in Italy and the US (in September and October 1965, respectively).

I'd dearly love to blame AIP, who released the film as a double bill with Die, Monster, Die!, for the all-out badness of Planet of the Vampires (Terrore nello spazio), but I can't. Yes, the film's English screenplay, penned by Ib Melchior and AIP producer Louis M. Heyward, is dire almost beyond belief, but it's a translation of an Italian script Bava himself cowrote. Sure, AIP gave the Italian just $100,000 to work with, but low budgets were never a problem for Bava before (see Black Sunday). And the all-round bad acting? Well, working with an international cast who didn't understand each other, Bava must take at least part of the blame for not getting better performances.

Two interplanetary spaceships, the Argos and the Galliott, approach the unexplored planet of Aura when they suddenly find themselves subjected to an enormous gravitational force. The ships lose contact, and the Argos' crew begin attacking each other under the influence of an unexplained force. Captain Mark Markary (Barry Sullivan) manages to contain his raging crew and land the Argos on Aura's barren, fog-covered surface.

Our plucky heroes go on an expedition to the Galliott, which has crashed not too far from the Argos, but find all her crew dead and conclude they killed each other in the same fit of madness. After burying the victims, however, crew member Tiona (Evi Marandi) believes she's seen the dead walking while standing watch. Eventually, they realise the planet is inhabited by a non-corporeal race who are possessing the dead humans for their own nefarious purposes.

You may have noticed the above summary doesn't include any vampires. The Aurans certainly don't count: they inhabit dead bodies, sure, but they don't drink blood, and no-one ever suggests taking a stake to them. It's much more Invasion of the Body Snatchers than Dracula, but hey, AIP had previously marketed more than one Bava film about vampires, so they must have decided that marketing the picture as 'vampires... in space!' was a great idea. (Commercially, it worked out.) Thankfully, I don't have to blame Bava for this too: the Italian title just means, more vaguely but also more accurately, 'terror in space'.

Logic isn't the script's strong suit. Well, that's putting it mildly: nothing in Planet of the Vampires makes a lick of sense. Instead of coherence, Bava and/or Melchior decide to load up the script with incessant technobabble - especially sad given the cheapness of the sets. The less said about the thespians the better: the cast of Planet of the Vampires are, despite the extenuating circumstances listed above, an exceedingly sorry lot, with Ángel Aranda plumbing the depths of unconvincing acting.

But it's still a Mario Bava film and therefore looks gorgeous. There's an absolutely terrific giallotastic pan and zoom over a roomful of corpses, for example. (Notice that our space explorers' symbol seems to be struck-out double lightning bolts, as if fighting fascism was their primary concern.)

As always in Bava's films, the lighting is vibrant to the point of garishness. The director used vast amounts of fog to obscure the cheapness of the papier-maché rocks of Aura, but at least he shot said fog and rocks exceedingly well, emphasising otherworldly reds, blues and gaudy greens:

Its visual beauty can't save Planet of the Vampires from succumbing to utter tedium. It takes a stronger reviewer than me to behold the boring, confusing story and woeful acting and not throw up one's hands, saying, 'I don't care'. The film lives on mainly thanks to critics' claim that it inspired Alien, despite Ridley Scott's insistence he hadn't seen Planet of the Vampires before making his masterpiece. If we must compare the two, it is sadly entirely to the detriment of the earlier film. It's no surprise that Bava never dabbled in science fiction again.

Despite having passed on Blood and Black Lace, AIP still wanted to distribute Bava's films, and they decided to get closer to the source. Thus it was that the maestro's next feature was financed jointly by AIP and Francoist Spain's Castilla Cooperativa Cinematográfica, and for the first time a Bava film was released almost simultaneously in Italy and the US (in September and October 1965, respectively).

I'd dearly love to blame AIP, who released the film as a double bill with Die, Monster, Die!, for the all-out badness of Planet of the Vampires (Terrore nello spazio), but I can't. Yes, the film's English screenplay, penned by Ib Melchior and AIP producer Louis M. Heyward, is dire almost beyond belief, but it's a translation of an Italian script Bava himself cowrote. Sure, AIP gave the Italian just $100,000 to work with, but low budgets were never a problem for Bava before (see Black Sunday). And the all-round bad acting? Well, working with an international cast who didn't understand each other, Bava must take at least part of the blame for not getting better performances.

Two interplanetary spaceships, the Argos and the Galliott, approach the unexplored planet of Aura when they suddenly find themselves subjected to an enormous gravitational force. The ships lose contact, and the Argos' crew begin attacking each other under the influence of an unexplained force. Captain Mark Markary (Barry Sullivan) manages to contain his raging crew and land the Argos on Aura's barren, fog-covered surface.

Our plucky heroes go on an expedition to the Galliott, which has crashed not too far from the Argos, but find all her crew dead and conclude they killed each other in the same fit of madness. After burying the victims, however, crew member Tiona (Evi Marandi) believes she's seen the dead walking while standing watch. Eventually, they realise the planet is inhabited by a non-corporeal race who are possessing the dead humans for their own nefarious purposes.

You may have noticed the above summary doesn't include any vampires. The Aurans certainly don't count: they inhabit dead bodies, sure, but they don't drink blood, and no-one ever suggests taking a stake to them. It's much more Invasion of the Body Snatchers than Dracula, but hey, AIP had previously marketed more than one Bava film about vampires, so they must have decided that marketing the picture as 'vampires... in space!' was a great idea. (Commercially, it worked out.) Thankfully, I don't have to blame Bava for this too: the Italian title just means, more vaguely but also more accurately, 'terror in space'.

Logic isn't the script's strong suit. Well, that's putting it mildly: nothing in Planet of the Vampires makes a lick of sense. Instead of coherence, Bava and/or Melchior decide to load up the script with incessant technobabble - especially sad given the cheapness of the sets. The less said about the thespians the better: the cast of Planet of the Vampires are, despite the extenuating circumstances listed above, an exceedingly sorry lot, with Ángel Aranda plumbing the depths of unconvincing acting.

But it's still a Mario Bava film and therefore looks gorgeous. There's an absolutely terrific giallotastic pan and zoom over a roomful of corpses, for example. (Notice that our space explorers' symbol seems to be struck-out double lightning bolts, as if fighting fascism was their primary concern.)

As always in Bava's films, the lighting is vibrant to the point of garishness. The director used vast amounts of fog to obscure the cheapness of the papier-maché rocks of Aura, but at least he shot said fog and rocks exceedingly well, emphasising otherworldly reds, blues and gaudy greens:

Its visual beauty can't save Planet of the Vampires from succumbing to utter tedium. It takes a stronger reviewer than me to behold the boring, confusing story and woeful acting and not throw up one's hands, saying, 'I don't care'. The film lives on mainly thanks to critics' claim that it inspired Alien, despite Ridley Scott's insistence he hadn't seen Planet of the Vampires before making his masterpiece. If we must compare the two, it is sadly entirely to the detriment of the earlier film. It's no surprise that Bava never dabbled in science fiction again.

Saturday, 14 January 2012

I love you, Dr Zaius

For some reason, 1968 was a standout year for science fiction. It saw the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Barbarella (granted, one of these things is not like the other), and it also gave the world a third sci-fi classic: the amazing, entertaining and profound Planet of the Apes, whose glory could not be sullied by inferior sequels.

A bit of sullying was done by Tim Burton's widely disliked 2001 remake, but even that film raked in mountains of cash; and thus it was that 20th Century Fox held on to the franchise rights and eventually put into production a prequel variously titled Caesar, Caesar: Rise of the Apes and Rise of the Apes before being released as Rise of the Planet of the Apes.

That clunky final title proves that Hollywood executives firmly believe that you, gentle reader, are too thick to comprehend precisely which apes they might be talking about; and so we're all on the same page, Sean O'Neal will now explain:

The captured chimpanzees end up at the labs of the horribly named Gen-Sys corporation, where scientist Will Rodman (James Franco) has just developed a new type of genetic therapy. ALZ-112, which repairs and improves brain function, may prove the longed-for and - hopes Will's boss, Jacobs (David Oyelowo) - lucrative cure for Alzheimer's. Of course, chimpanzees being imprisoned and studied by humans is a neat reversal of the situation Charlton Heston found himself in in the original, but I think 'constant dialogue' above summed it up pretty well.

The study's most promising test subject, a chimpanzee called Bright Eyes (Terry Notary), breaks free, attacks several handlers and, among much destruction, is gunned down by security guards just as Will is presenting his findings to the Board. Obviously, this disaster means no-one will ever fund Will's project again, and the chimpanzee handler, Franklin (Tyler Labine), is told to put down all the apes; but when Franklin discovers that Bright Eyes had given birth just prior to seemingly running amok, he can't bring himself to kill the infant, and Will agrees to take it home.

Within a couple of years, the chimpanzee, now named Caesar (Andy Serkis), has grown to maturity. Caesar, having benefited from the gene therapy his mother received while he was still in the womb, exhibits signs of extraordinary intelligence, including sophisticated sign language and a fully developed sense of self. Meanwhile (there's a lot of 'meanwhile' after the first act), Will has been successfully treating his father (John Lithgow) with ALZ-112, stemming the progress of his Alzheimer's, but after a few years antibodies have started developing. Will manages to persuade Jacobs to fund the development of another, better drug.

Meanwhile, Caesar attacks Will's neighbour (Joey Roche) and is confined to a primate shelter run by the pragmatic John Landon (Brian Cox) and his sadistic jerk son Dodge (Draco Malfoy). After having a tough time at first and becoming disillusioned with Will, Caesar eventually escapes, discovers the new ALZ-113 and takes it back to enhance the intelligence of his fellow apes. Who rise.

In truth, the human characters in this film exist for two purposes only: to set the plot in motion, and to react with shock/sympathy/speciesist arrogance to the apes' actions. (It's fitting that the non-human primates are listed first in the credits.) The lead isn't Franco, and it certainly isn't Freida Pinto, whose character is entirely superfluous to the film but exists because she's just so pretty. No, our hero - anti-hero, perhaps, but the film doesn't really make that case - is Caesar, and after the latter two Lord of the Rings films and Peter Jackson's King Kong, everyone knows that if you want your humanoid computer-generated characters portrayed right, you get Andy Serkis.

Serkis gives the best performance in the film, an earnest and subtle portrayal of a person who comes to realise that he has the power to liberate his kind and change the world. He's part Moses, part Che Guevara, and totally awesome. The other actors portraying apes come close, though, creating wonderfully rounded characters like the aggressive alpha male Rocket (Terry Notary again), solitary gorilla Buck (Richard Ridings), Methuselah Koba (Chris Gordon) and gentle orangutan Maurice (Karin Konoval). The last of these is my favourite character in the film, not only because I adore orangutans but also because his name is a shout-out to Maurice Evans, the hero who portrayed the greatest character in the history of cinema: Dr Zaius of the original film.

The best, most humane decision they ever made was not to use a single real ape in filming: every one of them is an actor's motion-capture work rendered in CGI, and it's quite beautiful, including the truly insane amounts of fur they had to create. I've resigned myself to the fact that on a large scale, CGI will never look as real as practical effects, which are real: compare the orcs (latex and make-up) to Gollum (CGI) in the Lord of the Rings films to see the difference. But CGI allows the creation of almost-real-looking things you could never do with old-school effects - and, as in this case, it helps avoid a great deal of unnecessary suffering caused by enslaving our fellow primates to perform for our amusement.

The dialogue Rise of the Planet of the Apes conducts with the original shows, though, how much our perception of great apes has changed in forty-odd years. In one of the film's key lines, Landon tells Will that '[t]hey're not people, you know'. The 1968 film argued that actually, they kind of were people, and how would you like it if someone locked you in a cage and studied you? (The analogy to racial slavery was unmistakeable.) The prequel, by contrast, sets out the apes' irreconcilable strangeness. Where the original's actors portrayed their apes as furry people, in 2011 they're all animal, aggressively physical, dextrous climbers, moving on all fours. (Caesar, of course, mostly walks on his hind legs, marking him as the leader.)

We're less certain of the similarities between us and our closest living relatives now, much more aware that we were and still are projecting aspects of ourselves onto great apes. (We did that even before we knew we have a common ancestor: see the medieval and early modern characterisation of the monkey as a clownish caricature of human beings.) In Rise of the Planet of the Apes, they're fascinating but often strange and violent. Wyatt films them to remind us that, pace decades of juvenile chimpanzees being cute on TV, an adult male of the species can grow 1.7m tall, has the strength of several people, and is prone to solving problems by violence.

It is, I should mention, a gorgeous film. Cinematographer Andrew Lesnie (of the Lord of the Rings films, King Kong, and I Am Legend, proving again the producers knew to get the best people for this project) uses colour to accentuate the apes' personhood at the expense of the literally paler human characters, while Wyatt's direction is brisk and fleet, stylish but not showy, and filled with references to killer animal films from King Kong to The Birds without ever being obnoxiously post-modern. While parts of the film are silly and overblown, certain concessions have to be made to the twenty-first-century blockbuster. Otherwise it's delightfully old-fashioned, entertaining and thoughtful.

A bit of sullying was done by Tim Burton's widely disliked 2001 remake, but even that film raked in mountains of cash; and thus it was that 20th Century Fox held on to the franchise rights and eventually put into production a prequel variously titled Caesar, Caesar: Rise of the Apes and Rise of the Apes before being released as Rise of the Planet of the Apes.

That clunky final title proves that Hollywood executives firmly believe that you, gentle reader, are too thick to comprehend precisely which apes they might be talking about; and so we're all on the same page, Sean O'Neal will now explain:

'Not just any apes, mind, but specifically, those apes with the planet - the one from those movies - whose planet will now rise, metaphorically speaking, to replace that earlier, non-ape planet. Of course, none of this would have been necessary had Tony Danza and Danny DeVito not stolen Going Ape! all those years ago.'The opening sequence prefigures what makes Rise of the Planet of the Apes special. A chimpanzee group is wandering the African jungle, and before we know it they're ambushed by humans; several apes are caught in nets and dragged off. This could be a standard scene, but it's notable for how totally subjectivity is reversed: the chimpanzees are subjects, persons, while the humans are faceless goons; and the visual quotes director Rupert Wyatt lifts from the famous scene of apes on horseback chasing human hunter-gatherers in Planet of the Apes underline the constant dialogue between the prequel and the original.

The captured chimpanzees end up at the labs of the horribly named Gen-Sys corporation, where scientist Will Rodman (James Franco) has just developed a new type of genetic therapy. ALZ-112, which repairs and improves brain function, may prove the longed-for and - hopes Will's boss, Jacobs (David Oyelowo) - lucrative cure for Alzheimer's. Of course, chimpanzees being imprisoned and studied by humans is a neat reversal of the situation Charlton Heston found himself in in the original, but I think 'constant dialogue' above summed it up pretty well.

The study's most promising test subject, a chimpanzee called Bright Eyes (Terry Notary), breaks free, attacks several handlers and, among much destruction, is gunned down by security guards just as Will is presenting his findings to the Board. Obviously, this disaster means no-one will ever fund Will's project again, and the chimpanzee handler, Franklin (Tyler Labine), is told to put down all the apes; but when Franklin discovers that Bright Eyes had given birth just prior to seemingly running amok, he can't bring himself to kill the infant, and Will agrees to take it home.

|

| Not a chimpanzee. |

Meanwhile, Caesar attacks Will's neighbour (Joey Roche) and is confined to a primate shelter run by the pragmatic John Landon (Brian Cox) and his sadistic jerk son Dodge (Draco Malfoy). After having a tough time at first and becoming disillusioned with Will, Caesar eventually escapes, discovers the new ALZ-113 and takes it back to enhance the intelligence of his fellow apes. Who rise.

In truth, the human characters in this film exist for two purposes only: to set the plot in motion, and to react with shock/sympathy/speciesist arrogance to the apes' actions. (It's fitting that the non-human primates are listed first in the credits.) The lead isn't Franco, and it certainly isn't Freida Pinto, whose character is entirely superfluous to the film but exists because she's just so pretty. No, our hero - anti-hero, perhaps, but the film doesn't really make that case - is Caesar, and after the latter two Lord of the Rings films and Peter Jackson's King Kong, everyone knows that if you want your humanoid computer-generated characters portrayed right, you get Andy Serkis.

Serkis gives the best performance in the film, an earnest and subtle portrayal of a person who comes to realise that he has the power to liberate his kind and change the world. He's part Moses, part Che Guevara, and totally awesome. The other actors portraying apes come close, though, creating wonderfully rounded characters like the aggressive alpha male Rocket (Terry Notary again), solitary gorilla Buck (Richard Ridings), Methuselah Koba (Chris Gordon) and gentle orangutan Maurice (Karin Konoval). The last of these is my favourite character in the film, not only because I adore orangutans but also because his name is a shout-out to Maurice Evans, the hero who portrayed the greatest character in the history of cinema: Dr Zaius of the original film.

The best, most humane decision they ever made was not to use a single real ape in filming: every one of them is an actor's motion-capture work rendered in CGI, and it's quite beautiful, including the truly insane amounts of fur they had to create. I've resigned myself to the fact that on a large scale, CGI will never look as real as practical effects, which are real: compare the orcs (latex and make-up) to Gollum (CGI) in the Lord of the Rings films to see the difference. But CGI allows the creation of almost-real-looking things you could never do with old-school effects - and, as in this case, it helps avoid a great deal of unnecessary suffering caused by enslaving our fellow primates to perform for our amusement.

The dialogue Rise of the Planet of the Apes conducts with the original shows, though, how much our perception of great apes has changed in forty-odd years. In one of the film's key lines, Landon tells Will that '[t]hey're not people, you know'. The 1968 film argued that actually, they kind of were people, and how would you like it if someone locked you in a cage and studied you? (The analogy to racial slavery was unmistakeable.) The prequel, by contrast, sets out the apes' irreconcilable strangeness. Where the original's actors portrayed their apes as furry people, in 2011 they're all animal, aggressively physical, dextrous climbers, moving on all fours. (Caesar, of course, mostly walks on his hind legs, marking him as the leader.)

We're less certain of the similarities between us and our closest living relatives now, much more aware that we were and still are projecting aspects of ourselves onto great apes. (We did that even before we knew we have a common ancestor: see the medieval and early modern characterisation of the monkey as a clownish caricature of human beings.) In Rise of the Planet of the Apes, they're fascinating but often strange and violent. Wyatt films them to remind us that, pace decades of juvenile chimpanzees being cute on TV, an adult male of the species can grow 1.7m tall, has the strength of several people, and is prone to solving problems by violence.

It is, I should mention, a gorgeous film. Cinematographer Andrew Lesnie (of the Lord of the Rings films, King Kong, and I Am Legend, proving again the producers knew to get the best people for this project) uses colour to accentuate the apes' personhood at the expense of the literally paler human characters, while Wyatt's direction is brisk and fleet, stylish but not showy, and filled with references to killer animal films from King Kong to The Birds without ever being obnoxiously post-modern. While parts of the film are silly and overblown, certain concessions have to be made to the twenty-first-century blockbuster. Otherwise it's delightfully old-fashioned, entertaining and thoughtful.

Labels:

apes,

blockbuster,

race,

revolution,

science fiction

Wednesday, 11 January 2012

Hanna; or, Life in the Woods

Goldarn, but it's shiny. Hanna

is the ultimate argument for style over substance, and it's a

compelling argument indeed. Joe Wright's fourth feature may well be

the best-shot film of 2011 not directed by Terence

Malick, and its score - given the same level of prominence as

Wright on the poster to your left - is used in ways that boggle and

delight the mind in equal measure.

If Hanna's successes all lie in gorgeous images and sounds, and not in an engaging story - well, what of it? Any argument based on the admitted flimsiness of the film's narrative risks becoming anti-cinematic if it doesn't acknowledge that meaning is communicated by visuals as much as it is by conventional storytelling. It's clear from Wright's directorial choices, though, that Hanna is not some bold formal experiment. It's just a little underwritten, and that's a darn shame.

Sixteen-year-old Hanna (Saoirse Ronan) lives in the wilderness of northern Finland with her father, Erik Heller (Eric Bana), a spy gone rogue. Having never seen civilisation, she's been raised to hunt, fight, and survive, and Erik has drilled her in languages and elaborate fake backstories. One day, Hanna realises she's 'ready', and Erik, with a heavy heart, allows her to press the big red button that will alert the CIA, from whom they've been hiding all these years, to their presence.

I adore this plot point beyond words. The fact that our heroes have been waiting all these years until they felt ready to start the plot with the push of a button gives the film something deliberate, makes us realise that while we like Hanna and Erik, they're nonetheless skilled and dangerous professionals. At this point, recall, we don't know what it is that they're choosing to unleash.

We soon find out, though. Erik's former handler, Marissa Wiegler (Cate Blanchett), sends out her goons, and they nab Hanna without finding Erik. In custody at an underground base, Hanna, underestimated by her captors, kills Marissa's body double (Michelle Dockery) and flees the base in a sequence that (a) is thrilling and exciting and (b) will induce epilepsy, if you're in an at-risk group. On the surface she realises she's in Morocco and must find her way to Berlin, where she's hoping to meet her father.

The score by the Chemical Brothers was heavily advertised, and it deserves the hype. Their neo-psychedelic electronica is pretty much perfect, propulsive while being eerie enough to be more than standard action music; Edvard Grieg's 'In the Hall of the Mountain King' is also used to great effect. It's not just the 'what', though, it's the 'how'. Not since Koyaanisqatsi - an experimental feature without narration, dialogue, or what you'd conventionally call plot - have I seen a film in which the beats of the scenes are dictated by music to such an extent. The action seems to serve the score, not the other way around.

We have Paul Tothill, a longtime Joe Wright collaborator, to thank for that: in his hands, Hanna is a wondrously taut, well-edited film, lapsing into manic rushes at just the right times and achieving serenity in others (the terrific scene in which Hanna, who's never experienced music before watches a Spanish dancer comes to mind). Wright himself is not as self-consciously ambitious as he was in 2007's Atonement, and that's a good thing: he's learnt to resist the temptation of flashiness.

Hanna is a visual wonder thanks to cinematographer Alwin Küchler's, who also shot the equally gorgeous Sunshine (2007). Unlike his earlier work, though, Küchler uses a much more subdued palette here, preferring blues and greens (there is, you'll be unsurprised to hear, a lot of turquoise). He emphasises Ronan's paleness and blue eyes through desaturation and lighting: the girl's almost-white face transports both vulnerability and, at the right times, menace.

You'll recall that around the same time Hanna was released Sucker Punch, another attempt to do substance by style, fell painfully flat. That Hanna does not suffer the same fate we can credit to Ronan, a young actress who really should be a much bigger star. Despite a distracting Teutonic accent she creates Hanna as a full human being - more importantly, a teenage girl. While the 'Hanna doesn't know how to interact socially' scenes are among the least successful, the same stretch of the film sees her reaching out to another girl her age, Sophie (Jessica Barden). The tender ambiguity of their relationship brings out the human longing for intimacy that underlies both friendship and romance in a character that, having grown up alone, has not had the social experience to distinguish the two.

Even as it falls flat in the story department (a final-act twist is both implausible and kind of lame) and suffers from Cate Blanchett's worst performance since Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, then, Hanna absolutely succeeds as a character study thanks to Ronan. Its cinematography and use of music are quite unlike anything you'll have seen before: and thus, while by no means flawless, Hanna is one of the most arresting and intriguing films of the year.

If Hanna's successes all lie in gorgeous images and sounds, and not in an engaging story - well, what of it? Any argument based on the admitted flimsiness of the film's narrative risks becoming anti-cinematic if it doesn't acknowledge that meaning is communicated by visuals as much as it is by conventional storytelling. It's clear from Wright's directorial choices, though, that Hanna is not some bold formal experiment. It's just a little underwritten, and that's a darn shame.

Sixteen-year-old Hanna (Saoirse Ronan) lives in the wilderness of northern Finland with her father, Erik Heller (Eric Bana), a spy gone rogue. Having never seen civilisation, she's been raised to hunt, fight, and survive, and Erik has drilled her in languages and elaborate fake backstories. One day, Hanna realises she's 'ready', and Erik, with a heavy heart, allows her to press the big red button that will alert the CIA, from whom they've been hiding all these years, to their presence.

I adore this plot point beyond words. The fact that our heroes have been waiting all these years until they felt ready to start the plot with the push of a button gives the film something deliberate, makes us realise that while we like Hanna and Erik, they're nonetheless skilled and dangerous professionals. At this point, recall, we don't know what it is that they're choosing to unleash.

We soon find out, though. Erik's former handler, Marissa Wiegler (Cate Blanchett), sends out her goons, and they nab Hanna without finding Erik. In custody at an underground base, Hanna, underestimated by her captors, kills Marissa's body double (Michelle Dockery) and flees the base in a sequence that (a) is thrilling and exciting and (b) will induce epilepsy, if you're in an at-risk group. On the surface she realises she's in Morocco and must find her way to Berlin, where she's hoping to meet her father.

The score by the Chemical Brothers was heavily advertised, and it deserves the hype. Their neo-psychedelic electronica is pretty much perfect, propulsive while being eerie enough to be more than standard action music; Edvard Grieg's 'In the Hall of the Mountain King' is also used to great effect. It's not just the 'what', though, it's the 'how'. Not since Koyaanisqatsi - an experimental feature without narration, dialogue, or what you'd conventionally call plot - have I seen a film in which the beats of the scenes are dictated by music to such an extent. The action seems to serve the score, not the other way around.

We have Paul Tothill, a longtime Joe Wright collaborator, to thank for that: in his hands, Hanna is a wondrously taut, well-edited film, lapsing into manic rushes at just the right times and achieving serenity in others (the terrific scene in which Hanna, who's never experienced music before watches a Spanish dancer comes to mind). Wright himself is not as self-consciously ambitious as he was in 2007's Atonement, and that's a good thing: he's learnt to resist the temptation of flashiness.

Hanna is a visual wonder thanks to cinematographer Alwin Küchler's, who also shot the equally gorgeous Sunshine (2007). Unlike his earlier work, though, Küchler uses a much more subdued palette here, preferring blues and greens (there is, you'll be unsurprised to hear, a lot of turquoise). He emphasises Ronan's paleness and blue eyes through desaturation and lighting: the girl's almost-white face transports both vulnerability and, at the right times, menace.

You'll recall that around the same time Hanna was released Sucker Punch, another attempt to do substance by style, fell painfully flat. That Hanna does not suffer the same fate we can credit to Ronan, a young actress who really should be a much bigger star. Despite a distracting Teutonic accent she creates Hanna as a full human being - more importantly, a teenage girl. While the 'Hanna doesn't know how to interact socially' scenes are among the least successful, the same stretch of the film sees her reaching out to another girl her age, Sophie (Jessica Barden). The tender ambiguity of their relationship brings out the human longing for intimacy that underlies both friendship and romance in a character that, having grown up alone, has not had the social experience to distinguish the two.

Even as it falls flat in the story department (a final-act twist is both implausible and kind of lame) and suffers from Cate Blanchett's worst performance since Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, then, Hanna absolutely succeeds as a character study thanks to Ronan. Its cinematography and use of music are quite unlike anything you'll have seen before: and thus, while by no means flawless, Hanna is one of the most arresting and intriguing films of the year.

Friday, 23 December 2011

Big trouble in little California