By 1964 the historical epic was on its way out. In the United States Cleopatra, doomed by its stupendous cost and the scandal surrounding its leads, had hastened the demise of the genre. In Italy pepla could always be cheaply made, but audiences were beginning to desert sword-and-sandal adventures in favour of the new kids on the block, the giallo and the spaghetti western. With the ancient epic as a whole went the colossal Bible adaptations of the fifties and early sixties, like The Ten Commandments (1956) and King of Kings (1961).

Curiously, though, the dying years of the biblical epic were in fact well suited to serious public explorations of religion. The papacy of John XXIII, culminating in the Second Vatican Council, marked an opening of the Catholic Church towards the world, a qualified departure from its previous defensive stance vis-à-vis modernity and possibly an ecclesiological revolution. As part of that, the Church became more willing to engage art produced by non-Catholics.

The non-Catholic that interests us here is Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italian novelist, director, poet, intellectual and pretty much every other cultural profession under the sun. An open atheist and communist, Pasolini was also followed by (well-founded) rumours of homosexuality in the tabloid press. He was, in short, precisely the sort of person the Syllabus of Errors of a more combative papacy was directed against. And yet Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew (Il vangelo secondo Matteo) - dedicated to the memory of John XXIII - is a stunning success, a far more interesting religious work than the often musty epics Hollywood had churned out. Armed with an unimpressive budget, Pasolini succeeds in making the most ubiquitous story in Western culture strange again.

He does this, first, by adapting only the Gospel of Matthew, shunning the usual approach of harmonising the gospels or filling in gaps in one with bits from the other. That approach often leads to ridiculousness in adaptation (witness talkative crucified Jesus in The Passion of the Christ) as well as cognitive dissonance, since we're taught not to realise that Matthew and Luke tell different and incompatible nativity stories. By sticking solely to Matthew, the film does not feature the birth of John the Baptist, the census and journey to Bethlehem (like Matthew's gospel, Pasolini implies Joseph and Mary are from Bethlehem), the birth of Jesus in a stable, the shepherds - and that's the nativity alone; later, we're not given the 'I am' statements, the woman caught in adultery, the wedding at Cana, Jesus and Zacchaeus, the parable of the Good Samaritan, doubting Thomas, and so on. By missing all these familiar elements, the narrative feels startling and strange; we see its shape, but it is not the shape of the gospel we think we know.

Instead, Pasolini - faithful to Matthew, I think - presents the story mostly as an escalating conflict between Jesus and the Jewish civil and religious authorities. He emphasises Herod's massacre of the innocent at Bethlehem, repeatedly stressing the violence of the authorities. We see Jesus react tearfully to the murder of John the Baptist, but determined to continue his mission. Under pressure in Jerusalem, he retreats into the company of the Twelve, with whom he eats a final supper at a safe house before being betrayed, arrested and executed, and rising again on Sunday.

At the heart of Pasolini's gospel story is Jesus (and, before him, John the Baptist) challenging the institutions and representatives of Israel to accept him as Messiah. Rejected, he begins forming an alternative Israel consisting of the poor, the disreputable and the sick - an upside-down kingdom that pointedly confronts the authorities. The victory of established Israel - capturing, convicting and executing Jesus - proves an illusion, as he rises and commissions his followers to extend his kingdom to the whole earth. Because the old Israel rejected Jesus, it has now been rejected by God.

That storyline, of course, is why Matthew's gospel is often accused of antisemitism - a charge that seems basically accurate, although anti-Jewish rhetoric from a precarious first-century Messianic sect is undoubtedly different from the modern-day scourge. Pasolini avoids that problem by de-contextualising Matthew's Jesus-against-the-Jews story through the deliberate use of anachronism. Herod's soldiers are dressed like medieval warriors and Spanish conquistadors, and the film uses the Romanesque and Gothic churches of Basilicata and Apulia for sets. The soundtrack features well-known pieces of religious music from Händel to Blind Willie Johnson's "Dark Was the Night". By mixing symbols from two thousand years of Christian history, Pasolini's film is at once about first-century Palestine and the hope of a whole crushed humanity in Jesus. First-century events are thus imbued with an eschatological dimension.

At the same time, Pasolini undercuts folk orthodoxy at several points. Salome, whose dance before Herod II leads to the execution of John the Baptist, is portrayed as a nervous teenage girl under the thrall of her mother, not the lascivious temptress of tradition. Jesus, meanwhile, is not the serenely smiling figure of religious art; Spanish student Enrique Irazoqui portrays him as angry, driven, and ultimately inscrutable. The other actors, local amateurs all, predictably give flat, affectless performances - which, given Pasolini's copious use of the Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, is as it should be.

The Gospel According to St. Matthew is not the plain Marxist allegory Pasolini was expected to produce. Pasolini's Jesus is, instead, the Christ of liberation theology: in his ministry God's kingdom - inaugurated by his death at empire's hands - and the embrace of the oppressed are inextricably bound up. The audience, though, is not put in a comfortable position of solidarity. Pasolini films the trial of Jesus over the shoulders of the jeering crowd, implicating the viewer in the rejection of Jesus. His Jesus is not reducible to a single lesson or pat truth. The suffering of mankind bound up in him, he remains mysterious - but endlessly fascinating.

Showing posts with label antiquity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label antiquity. Show all posts

Sunday, 21 April 2013

To serve and give his life as a ransom for many

Labels:

antiquity,

empire,

Jesus,

Marxism,

Redemption Day

Tuesday, 13 March 2012

Theseus war

Like it or not, 300 changed everything.* After hubris and audience fatigue had caused the ancient epic of the early 2000s to collapse, Zack Snyder's 2007 debut transformed the sword-and-sandal film into its present form. The subgenre of hyper-masculine, deliberately artificial-looking mid-budget pictures is still not dead, despite the fact that it has yet to produce an actual good film apart from its progenitor.

Immortals, alas, isn't the yearned-for exception to the rule. Whatever the intentions of the people behind it, the finished product is a rip-off of 300 by way of Clash of the Titans. Whatever other merits 300, a film I liked, might claim, it was hardly the womb of ideas; and if you're copying a remake, well... Suffice it to say that Immortals follows previous sword-and-sandal films so slavishly that it ends up with no identity of its own to speak of.

Anyway, the film is the story of Theseus (Henry Cavill), though considering the indifference with which the script treats Greek mythology I don't know why they bothered. Theseus is raised in a nameless village by his mother (Anne Day-Jones) and High Chancellor Sutler (John Hurt). When the evil king Hyperion (Mickey Rourke) sends out his armies in search of the fabled Epirus Bow, Theseus is enslaved, but he soon escapes with a ragtag bunch of misfits including the thief Stavros (Stephen Dorff) and the virgin oracle Phaedra (Freida Pinto).

Meanwhile the Olympians, led by Zeus (Luke Evans, who played Apollo in Clash of the Titans), fear that Hyperion may use the Epirus Bow to release the imprisoned Titans, but will not interfere with the affairs of mankind. Theseus finds the bow in a rock, and they take the weapon to Mount (!) Tartarus, where a Hellenic army has gathered to protect the Titans' prison from Hyperion's fanatical hordes. Along the way, they of course manage to lose the bow to Hyperion, setting the scene for an ugly showdown.

The script is quite simply boring as hell, and no-one could blame the actors for failing to breathe any life into it. Considering they use a literal deus ex machina more than once when the heroes find themselves in a pickle, writers Charley and and Vlas Parlapanides were presumably not taking their job too seriously. The story is padded to twice the necessary length, while still being something of a skeleton to hang an actual plot on: there isn't the slightest suggestion of geography or ethnography, real or fictional. One presumes the film is set in some fictionalised version of a country the script refers to as 'Hellenes', presumably because 'Greece' is too vulgar and 'Hellas' is too correct. The one good idea - the fight against the Minotaur, who is a large, brutish human wearing a wire bull's mask here - seems shoehorned in and is lost in a sea of awfulness.

The visuals don't help at all. Sure, the film's notion of Olympus - here, a darkish set populated by gods wearing silly hats - is better than the tinfoil-and-eyeliner extravaganza Clash of the Titans tried to sell us. Director Tarsem Singh conjures up some striking images, but it's all thoroughly ruined by the colour scheme, the very same mix of dark brown and gold with occasional dashes of colour that 300 should by all rights have killed off. That a very narrow aesthetic should dominate a subgenre would be merely irritating; but it really undoes Immortals, for what better way to declare yourself a 300 clone than to ape every detail of that film's look? Let's hope the upcoming Wrath of the Titans at last puts a stake through the heart of the sword-and-sandal film so that one day there'll be worthwhile films about the ancient world.

*Pathfinder, released a month after 300, may be safely ignored, since unlike the Spartan massacre it sank like a stone at the box office.

Immortals, alas, isn't the yearned-for exception to the rule. Whatever the intentions of the people behind it, the finished product is a rip-off of 300 by way of Clash of the Titans. Whatever other merits 300, a film I liked, might claim, it was hardly the womb of ideas; and if you're copying a remake, well... Suffice it to say that Immortals follows previous sword-and-sandal films so slavishly that it ends up with no identity of its own to speak of.

Anyway, the film is the story of Theseus (Henry Cavill), though considering the indifference with which the script treats Greek mythology I don't know why they bothered. Theseus is raised in a nameless village by his mother (Anne Day-Jones) and High Chancellor Sutler (John Hurt). When the evil king Hyperion (Mickey Rourke) sends out his armies in search of the fabled Epirus Bow, Theseus is enslaved, but he soon escapes with a ragtag bunch of misfits including the thief Stavros (Stephen Dorff) and the virgin oracle Phaedra (Freida Pinto).

Meanwhile the Olympians, led by Zeus (Luke Evans, who played Apollo in Clash of the Titans), fear that Hyperion may use the Epirus Bow to release the imprisoned Titans, but will not interfere with the affairs of mankind. Theseus finds the bow in a rock, and they take the weapon to Mount (!) Tartarus, where a Hellenic army has gathered to protect the Titans' prison from Hyperion's fanatical hordes. Along the way, they of course manage to lose the bow to Hyperion, setting the scene for an ugly showdown.

The script is quite simply boring as hell, and no-one could blame the actors for failing to breathe any life into it. Considering they use a literal deus ex machina more than once when the heroes find themselves in a pickle, writers Charley and and Vlas Parlapanides were presumably not taking their job too seriously. The story is padded to twice the necessary length, while still being something of a skeleton to hang an actual plot on: there isn't the slightest suggestion of geography or ethnography, real or fictional. One presumes the film is set in some fictionalised version of a country the script refers to as 'Hellenes', presumably because 'Greece' is too vulgar and 'Hellas' is too correct. The one good idea - the fight against the Minotaur, who is a large, brutish human wearing a wire bull's mask here - seems shoehorned in and is lost in a sea of awfulness.

The visuals don't help at all. Sure, the film's notion of Olympus - here, a darkish set populated by gods wearing silly hats - is better than the tinfoil-and-eyeliner extravaganza Clash of the Titans tried to sell us. Director Tarsem Singh conjures up some striking images, but it's all thoroughly ruined by the colour scheme, the very same mix of dark brown and gold with occasional dashes of colour that 300 should by all rights have killed off. That a very narrow aesthetic should dominate a subgenre would be merely irritating; but it really undoes Immortals, for what better way to declare yourself a 300 clone than to ape every detail of that film's look? Let's hope the upcoming Wrath of the Titans at last puts a stake through the heart of the sword-and-sandal film so that one day there'll be worthwhile films about the ancient world.

*Pathfinder, released a month after 300, may be safely ignored, since unlike the Spartan massacre it sank like a stone at the box office.

Monday, 20 February 2012

Hyborian twilight

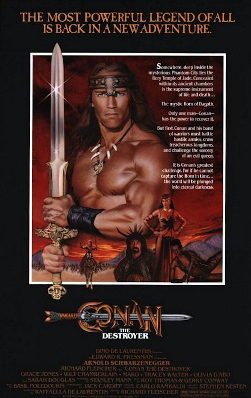

Like its predecessor, Conan the Destroyer didn't set cinema on fire. But in an industry of marginal profits, the film's considerable success at the box office made a third film set in the world of Robert E. Howard all but inevitable. That film, Conan the Conqueror - the long-promised story that shall also be told, of how Conan became a king in his own hand -, never left development hell; and for that we can thank the ignominious failure of the series spin-off Red Sonja.

Like its predecessor, Conan the Destroyer didn't set cinema on fire. But in an industry of marginal profits, the film's considerable success at the box office made a third film set in the world of Robert E. Howard all but inevitable. That film, Conan the Conqueror - the long-promised story that shall also be told, of how Conan became a king in his own hand -, never left development hell; and for that we can thank the ignominious failure of the series spin-off Red Sonja.Red Sonja's production was rushed compared to the two-year gap between the Conan films. I've remarked on the breakneck pace the Italian film industry was capable of in its glory days, and if Richard Fleischer did not quite match Mario Bava's feat of releasing two of his films twelve days apart, it's still worth noting that Conan the Destroyer left cinemas in August 1984 and principal photography for Red Sonja took place that same November, for a summer 1985 release. That sort of pace may be common in low-budget horror, but it's quite something for sword and sorcery, which calls for massive sets, landscape photography and epic battles.

Those three months during the autumn of 1984, however, saw the release of The Terminator. That film's massive success - a worldwide gross of $78 million, comparable to the Conan films but nothing to sniff at considering it had only a third of the sword-and-sorcery films' budget - suggested to Schwarzenegger that he had a legitimate, loincloth-free career ahead of him. When Red Sonja bombed, taking in less than $7m on a $17.9m budget, he abandoned the barbarian genre and became the action/comedy star - and eventually the politician and philanderer - we know and possibly still love today.

When Red Sonja (Brigitte Nielsen) rejects the lesbian advances of the evil queen Gedren (Sandahl Bergman), Gedren has her family murdered while Sonja is raped by her soldiers and left for dead before being revived by a spirit voice. (It's never revealed who this spirit - who speaks to Sonja only twice in the course of the film, never in a plot-relevant function - is, which strikes me as one of the tell-tale signs of a script that was butchered and stitched together again by some literary Leatherface.)

Later, somewhere else, a group of priestesses tries to destroy a dangerous talisman, but they're attacked and killed by the goons of Gedren, who wants the power of the talisman for herself to rule the world. Sonja's sister Varna (Janet Agren) manages to flee, but is shot in the back before being rescued by random hero-lord 'Kalidor' (Arnold Schwarzenegger). It remains one of the film's mysteries why it was felt necessary to create a character who is clearly Conan with the serial numbers filed off: legal reasons, perhaps. Anyway, Kalidor messily kills several of Gedren's goons (Red Sonja cranks up the gore to Conan the Barbarian levels again, after the tamer Destroyer) and carries the dying Varna off to Sonja, who has been trained as a mighty warrior by a vaguely Oriental sword-master (Tad Horino).

When Sonja finds out what's going on, she decides to stop Gedren, initally leaving Kalidor who nonetheless, as Tim Brayton puts it, 'just pops in like a wacky neighbor on a sitcom' during the film's first half. She fights and kills the warlord Brytag (Pat Roach) for no discernible reason and encounters Tarn (Ernie Reyes Jr.) and Falkon (Paul Smith), a child prince and his manservant who have lost their kingdom to Gedren's newly powerful forces. Eventually, the four make it through the wilderness, encountering exactly no people, and square off against Gedren and her magic tricks.

Though undeniably very bad - if Schwarzenegger's jest about punishing his progeny by subjecting them to this film were true, it would constitute child abuse - Red Sonja is at least as 'good' as Conan the Destroyer, and feels a lot better by mercifully coming in under ninety minutes. Written by two Britons, Clive Exter (who later wrote no fewer than twenty-three episodes of Jeeves and Wooster, if you can believe it) and George MacDonald Fraser (who co-wrote Octopussy), Red Sonja's plot is as unsteady and aimless as that of the preceding films, but it's a whole lot less padded, avoiding the cosmic tedium of Destroyer's sleepy second half. The worst thing you can say about is that it introduces that shopworn trope, the Annoying Kid; but at least Tarn turns heroic fairly early on.

At the same time, the casting departments must have been mad as a hatter convention, for the sheer number of series veterans re-cast in totally different roles makes viewing a profoundly baffling experience. Besides Schwarzenegger - who, as the film's most bankable star, is billed above the then unknown Nielsen - there's Bergman, who played Conan's true, sadly nameless love in Barbarian, rendered less recognisable by a mask covering half her face, a fairly terrible black wig, and a deliciously hammy performance. The casting of Pat Roach, who played the illusionist Toth-Amon in Destroyer, as the villainous Brytag is less justifiable, especially since his cameo is mere padding. Danish bodybuilder Sven-Ole Thorsen, however, takes the cake, with his third character in as many films.

Schwarzenegger's performance is, well, vintage Arnie: no-one could make a line like 'She's dead. [Pause.] And the living have work to do' sound quite so earnest yet hilarious. But let's consider Brigitte Nielsen for a moment. Twenty-one years old, with no real acting experience, her uninflected, wooden performance is truly horrendous in exactly that oddly fitting Schwarzeneggerian mould, and they're perfectly matched on set. But where the Austrian reached superstardom, Nielsen briefly became Mrs Sylvester Stallone, met Ronald Reagan, appeared in Playboy a couple of times and has lived out the rest of her career on reality television. Just a few weeks ago, Nielsen won the German version of I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here!.

Richard Fleischer, returning to the director's chair after Conan the Destroyer, largely keeps it steady. At some point, though, he must have decided to prove that a leopard can change its spots and also why it shouldn't, by serving up a couple of absolutely nonsensical first-person shots during sword-fighting scenes. It's in the special effects department that Red Sonja is a real let-down, however. Whether it was time or money, the film resorts to mattes - gorgeously painted mattes, I grant - where John Milius in his Barbarian days would probably have built a full set. Contrast the visuals of Conan the Barbarian with the pretty but totally artificial look of Red Sonja:

The costumes and sets, alas, are the series' weakest by far, preposterous without once looking striking. In one battle scene - I'm not making this up, I swear - one mook wears blue jeans, which I'm fairly sure were not invented in the Hyborian Age. And speaking of battles, the swordfighting - choreographed by stunt coordinator Sergio Mioni, I presume - is noticeably worse than in either of the earlier films. Saddled with a leaden script, poor effects and an extraordinarily lazy Ennio Morricone score, Red Sonja cannot help being terrible; but while not as rousing as the first film, it is at least less infuriating than Conan the Destroyer.

In this series: Conan the Barbarian (1982) | Conan the Destroyer (1984) | Red Sonja (1985) | Conan the Barbarian (2011)

Tuesday, 14 February 2012

If your neighbour worships twenty gods: a note on biblical law and religious toleration

Christians are used to seeing secular society - whose institutions favour no particular faith - as a dire threat. To John Piper, for example, '[t]he modern secular world... tries to remove God from his all-creating, all- sustaining, all-defining, all-governing place [and] has no choice but to make itself god'. In other words, a secular society is blasphemous by definition. Against this conservative appraisal, I'll suggest secularism is most fruitfully understood not as a menace destroying western civilisation from within, but as a blessing longed for by those who did not enjoy it, made possible by Jesus' death on the cross.

At the same time, I'll argue that the liberal understanding of secularism is ahistorical and impossible to square with biblical evidence. Here, for example, is the excellent blogger Fred Clark, arguing against the US Catholic bishops' attempt to stop contraceptive services for women:

'It does me no injury,' Thomas Jefferson wrote, 'for my neighbour to say there are 20 gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.' The advocates of burka-logic [sic] disagree. They insist that the very presence of such irreligious neighbors does them an injury - the injury of constraining their freedom to live unperturbed by the constant reminder of such blasphemies.This quintessentially liberal argument - my neighbour's religious predilections do me no harm, so I have no business constraining him - cannot survive an encounter with the God of the Old Testament. At Sinai God makes a covenant is with Israel as a community to ensure correct religious observance and moral behaviour in the land (Deuteronomy 1:1-14). The Mosaic Law does not offer any room for religious toleration. Indeed the Israelites are explicitly commanded to destroy all traces of Canaanite paganism if they wish to enjoy the land (Deuteronomy 12:1-4).

Contrary to Jefferson, under Old Testament law my neighbour's heterodox religious observance does pick my pocket and break my leg. The Religious Right's notion of 'individual responsibility' is quite absent in the Bible. God repeatedly threatens to punish people for sins they have not themselves committed, 'visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children's children, to the third and fourth generation' (Exodus 20:5, Exodus 34:7, Numbers 14:18, Deuteronomy 5:9, and many more). Positively, God considers whole communities more kindly on account of a few righteous people (Genesis 18:22-32, Romans 11:28).

The insistence that Israel is judged as a whole for the actions committed in its midst rather than as individuals is perhaps best encapsulated by Deuteronomy 21:1-9:

If in the land that the LORD your God is giving you to possess someone is found slain, lying in the open country, and it is not known who killed him, then your elders and your judges shall come out, and they shall measure the distance to the surrounding cities. And the elders of the city that is nearest to the slain man shall take a heifer that has never been worked and that has not pulled in a yoke. And the elders of that city shall bring the heifer down to a valley with running water, which is neither ploughed nor sown, and shall break the heifer's neck there in the valley. Then the priests, the sons of Levi, shall come forward... And all the elders of that city nearest to the slain man shall wash their hands over the heifer whose neck was broken in the valley, and they shall testify, 'Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it shed. Accept atonement, o LORD, for your people Israel, whom you have redeemed, and do not set the guilt of innocent blood in the midst of your people Israel, so that their blood guilt be atoned for.' So you shall purge the guilt of innocent blood from your midst, when you do what is right in the sight of the LORD.Here the murderer is unknown and unidentifiable, but the nearest settlement is required to offer a sacrifice in atonement for the sin committed lest it be visited upon their heads. The action, not the acting subject, is the primary term. Nor does the Bible consider the motives of offenders. Distinguishing murder from accidental killings, for example, is an innovation of the ninth century, when earnest scholars attempted to settle matters humanius (more humanely) than the often harsh Church Fathers. (So much, incidentally, for the notion that a concern for human welfare reveals a 'man-centred' world-view.)

We tend to take a modern legal understanding of individual responsibility for granted, but it can seriously distort our reading of the Bible. The concept of bloodguilt - that sin, if unatoned, will return to haunt even those who have not themselves committed it - is accepted by New Testament writers (Luke 11:50-51, Revelation 6:10). Augustine's notion that original sin is passed on through biological parenthood - logically consigning those who die in the womb to damnation - would also be impossible without bloodguilt.

But that isn't the whole story. In the New Testament, God's people are not told to enforce obedience among their nonbelieving neighbours. Indeed the New Testament is marked by disinterest in secular power at best, and outright hostility at worst (Revelation 17:1-6). The death of Jesus at the cross changes everything. From that point onwards, it is not biological descent from Abraham but faith that determines membership in the people of God (Romans 9:30). The ethno-religious boundaries of ancient Israel have been shattered. God's people are now of every nation and tongue, no longer identifiable with individual peoples or states.

Secularism - a society no longer compelled to enforce religious obedience among its subjects, on pain of judgment - is thus made possible by the death of Jesus. When an individual puts her faith in Christ she cannot become his without also becoming part of the people of God; God's covenant is made with his people as a whole. There is no salvation for the individual outside the collective salvation of God's people (which is why I continue to find Calvinism's emphasis on Christ's successful purchase of a definite people compelling). It is because of this ingrafting into the people of God that baptism - a public symbol of membership in God's family - is important. But it no longer coincides with membership in an earthly nation or obedience to a set of temporal laws.

If the potential for secularism was present from Jesus' death onwards, that potential had to remain unrealised in pre-modern societies, which functioned through personal relationships and localised hierarchies sealed and enforced through oaths. Public declarations of political and religious loyalty - which are quite superfluous in modern states - were vital to rulers who lacked the centralised bureaucracy necessary to enforce obedience among their subjects. (For example, a modern state knows who all its subjects are and where they live, something the ancients could not have imagined in their wildest dreams.)

Even the Roman state, often praised for its tolerance, could not solve the problem of religious diversity by becoming secular - atheist as a state - but only by being radically inclusivist, declaring all faiths valid and adding foreign deities to its pantheon. Still, it required that its subjects subordinate their loyalties to the imperial cult, and those who could not comply - Christians, most famously - had to suffer its wrath. Pre-modern societies that did not compel everyone's conversion (the political entities of the Islamic world, for example) nonetheless had to privilege one faith.

It was only with the vastly increased capacity of the state from the French Revolution onwards, and its sweeping aside of motley feudal ties and privileges, that overwhelmingly Christian societies could provide freedom of religion for their subjects without breaking down. Our nonconformist forebears - the very people from whom modern evangelicalism is descended - ardently campaigned and prayed for a secular state that would not exclude them on the basis of religion, and eventually obtained that sweet freedom.

Labels:

antiquity,

Christianity,

conservatism,

early modern age,

evangelicalism,

historical materialism,

Jesus,

liberalism,

the middle ages

Friday, 10 February 2012

Conan: the LARP years

Films don't have to be spectacular box office successes to inspire legions of knock-offs. Conan the Barbarian doubled its $20 million budget domestically, grossed almost $69 million worldwide and turned Dino de Laurentiis's flagging fortunes around for a few years, but it was by no means an international smash. What attracted the vultures, instead, was Conan's readily replicable formula: wizards, leather-clad strongmen, and fanservice in furs.

In the 1980s, Conan copies like The Beastmaster and the Ator films multiplied on both sides of the Atlantic. The great Italian rip-off machine, no stranger to casting bodybuilders in garish adventures since the 1950s, was particularly reinvigorated by the Styrian's signature role, but Conan's influence was widespread and long-lasting. From Hercules: The Legendary Journeys to - just maybe - The Lord of the Rings, John Milius's film changed history.

It was inevitable that there should be a sequel. 1984's Conan the Destroyer enjoyed healthy box office takings, a fact that directly led Schwarzenegger to team up with Dino de Laurentiis for the following year's ill-fated Red Sonja. It was, however, widely disliked upon release - and rightly so, for Conan the Destroyer is a very bad film. It feels in every way like a made-for-TV knock-off rather than a sequel to Conan the Barbarian.

An unspecified amount of time after the events of the first film, Conan (Arnold Schwarzenegger) and his new sidekick Malak (Tracey Walter) are ambushed by goons who try to capture them in nets. After some slaughter, Conan is approached by the enemies' leader, Queen Taramis of Shadizar (Sarah Douglas), with a proposition: he is to escort her niece, Princess Jehnna (Olivia d'Abo), on a mission to retrieve the horn of the sleeping god Dagoth. Learning that this will involve confronting the wizard Toth-Amon, Conan initially refuses: 'What good is a sword against sorcery?' (That's a question which I thought the ending of Conan the Barbarian answered sufficiently, but whatever.) He relents, however, when Taramis promises that she will resurrect Conan's dead love interest Valeria. (In one of the oddities of continuity, Valeria is never named in Conan the Barbarian but regularly name-checked in the sequel.)

Conan accepts, and sets off on his quest - without having sex with Taramis, which I suppose counts as character development - accompanied by Jehnna, Malak, and the captain of Taramis's guard, Bombaata (Wilt Chamberlain). On their way to the evil sorcerer's castle, they pick up the wizard Akiro (Mako) of the first film, as well as the warrior woman Zula (Grace Jones). The party thus complete, they confront the illusionist Toth-Amon, defeat him, and retrieve the jewel that will allow access to Dagoth's jewelled horn.

This is about forty minutes in, and there's enough material left for perhaps fifteen minutes. Bombaata's real task is to kill Conan and abduct Jehnna so she can be sacrificed to Dagoth, but instead of getting on with it the padding kicks in: now our heroes have to travel to a temple where Dagoth's horn is kept, and this gives the filmmakers time to put us through long, gruelling dialogue and 'comic relief' regarding Jehnna's crush on Conan. That slack second half is in precise contrast to Conan the Barbarian, which accomplished its bumbling early on and then gained steam.

Conan the Destroyer feels less like the 1982 film than its knock-offs because, of course, it was penned by knock-off writers. No, not screenwriter Stanley Mann of Damien: Omen II, Firestarter and little else, but the duo who developed the story, Roy Thomas and Gerry Conway, who'd previously churned out the animated sword-and-sandal picture Fire and Ice and, in Thomas's case, worked on the television series Thundarr the Barbarian. Their work is inferior to that of John Milius and Oliver Stone in the original film in every respect, but let's start with the villains. Conan the Barbarian had Thulsa Doom, a terrific baddie played to perfection by James Earl Jones. In Destroyer, our heroes are menaced by this guy:

He turns into this when he wants to be extra-terrifying:

Need I say more?

Did Thomas & Conway - or anyone else, for that matter - really leave Conan the Barbarian thinking, 'This was pretty cool, but I wish Conan talked more/had a bunch of sidekicks/made more jokes?' Dino de Laurentiis apparently thought the first film's box office take had been hurt by its R rating, and subsequently worked hard to make Destroyer PG-13 by removing the nudity and gore of the original, but that's not where the problem lies. That would be sticking Conan into a tedious, padded story with limited personal stakes (no real effort is made to convince us of Conan's desire to bring Valeria back), and the sidekicks.

Ah yes! For this film replaces the mostly silent trio of the original (Conan, Subotai, Valeria) with, well, a party. It really does feel like a particularly unimaginative role-playing campaign, although at least they don't all meet in an inn. There are scenes that feel particularly Dungeons & Dragons: the ape-man at Toth-Amon's castle, for example, who can only be defeated by smashing all the mirrors in the room.

Mako as the wizard Akiro is a welcome presence, as is Wilt Chamberlain's Bombaata. I'm on the fence about Grace Jones as Zula: she's awesome, but her archetype - the savage warrior woman - is pretty racist, especially when contrasted with the exceedingly Aryan princess Jehnna. Malak, however, is perhaps the most wretched comic relief character before Jar Jar Binks. Tracey Walter, who's since carved out a very respectable career on television, is visibly miserable and unconvinced by the role. No-one could blame him: it isn't easy for actors to find work. Blame, instead, falls once more to Thomas & Conway, who should have remembered that comic relief is generally intended to be funny (hence 'comic').

Undone by an awful, meandering script, Conan the Destroyer holds up pretty well in other departments. Richard Fleischer, director of The Vikings and other sword-and-sandal pictures of the 1950s and 1960s, does his best to make the film no more boring than it has to be, and he's helped by the director of photography, fellow Vikings alumnus Jack Cardiff (who also shot the 1951 Bogart-Hepburn classic The African Queen). There is, in fact, a whiff of a last hurrah for the old guard surrounding Conan the Destroyer: the sword-and-sandal film of a previous generation going down in a blaze of sleepy non-glory. But in any case, they go down with some honestly pretty pictures:

Conan the Destroyer's budget was less than Barbarian's, and it seems more than once that being unable to afford something like the first film's majestic Mountain of Power they settled for a bunch of people bumbling around cheap-looking sets. But again, it's the fault of the writers who decreed that there must be crystal castles and temples covered in runes. In truth, Pier Luigi Basile's production design is good, great in the case of Queen Taramis's impressive throne room; and the same goes for the costumes, although there are some unconvincing wigs.

The single most disappointing aspect of the whole affair is that composer Basil Poledouris apparently zoned out. Poledouris's score for Conan the Barbarian has become a classic in its own right, but his work on the sequel is just tired. When he isn't plagiarising himself - the music from Barbarian's human soup scene is recycled for Destroyer's offering to Dagoth - it's just decidedly less exciting. Where Barbarian's music screamed epic!, the Destroyer score mutters, 'I was made for Saturday afternoon reruns'.

It's as if they went out of their way to remind the audience that Barbarian was a better film. When Malak says, and I'm quoting from memory here, 'LOOK, CONAN, IT'S A CAMEL, JUST LIKE THE ONE YOU PUNCHED IN THE FACE IN CONAN THE BARBARIAN' it would just be a clunky continuity nod - were it not for the fact that, being kicked off by a character not present in the original film, the scene suggests Conan boasts of his ignoble history of animal abuse to his companions.

If ever the title of a film improved upon Conan the Barbarian, surely it was Conan the Destroyer; but alas, reality proves otherwise. Not only does the promised destruction fail to ensue, we still don't learn how Conan became a king by his own hand, let alone what manner of crown he wore upon a troubled brow. The film's thorough failure is perhaps best summed up when Queen Taramis says,'What is there, Conan? Think!', and her suggestion does not strike us as self-evidently ridiculous. As for Thomas & Conway: fine writers you are - go back to juggling apples.

In this series: Conan the Barbarian (1982) | Conan the Destroyer (1984) | Red Sonja (1985) | Conan the Barbarian (2011)

In the 1980s, Conan copies like The Beastmaster and the Ator films multiplied on both sides of the Atlantic. The great Italian rip-off machine, no stranger to casting bodybuilders in garish adventures since the 1950s, was particularly reinvigorated by the Styrian's signature role, but Conan's influence was widespread and long-lasting. From Hercules: The Legendary Journeys to - just maybe - The Lord of the Rings, John Milius's film changed history.

It was inevitable that there should be a sequel. 1984's Conan the Destroyer enjoyed healthy box office takings, a fact that directly led Schwarzenegger to team up with Dino de Laurentiis for the following year's ill-fated Red Sonja. It was, however, widely disliked upon release - and rightly so, for Conan the Destroyer is a very bad film. It feels in every way like a made-for-TV knock-off rather than a sequel to Conan the Barbarian.

An unspecified amount of time after the events of the first film, Conan (Arnold Schwarzenegger) and his new sidekick Malak (Tracey Walter) are ambushed by goons who try to capture them in nets. After some slaughter, Conan is approached by the enemies' leader, Queen Taramis of Shadizar (Sarah Douglas), with a proposition: he is to escort her niece, Princess Jehnna (Olivia d'Abo), on a mission to retrieve the horn of the sleeping god Dagoth. Learning that this will involve confronting the wizard Toth-Amon, Conan initially refuses: 'What good is a sword against sorcery?' (That's a question which I thought the ending of Conan the Barbarian answered sufficiently, but whatever.) He relents, however, when Taramis promises that she will resurrect Conan's dead love interest Valeria. (In one of the oddities of continuity, Valeria is never named in Conan the Barbarian but regularly name-checked in the sequel.)

Conan accepts, and sets off on his quest - without having sex with Taramis, which I suppose counts as character development - accompanied by Jehnna, Malak, and the captain of Taramis's guard, Bombaata (Wilt Chamberlain). On their way to the evil sorcerer's castle, they pick up the wizard Akiro (Mako) of the first film, as well as the warrior woman Zula (Grace Jones). The party thus complete, they confront the illusionist Toth-Amon, defeat him, and retrieve the jewel that will allow access to Dagoth's jewelled horn.

This is about forty minutes in, and there's enough material left for perhaps fifteen minutes. Bombaata's real task is to kill Conan and abduct Jehnna so she can be sacrificed to Dagoth, but instead of getting on with it the padding kicks in: now our heroes have to travel to a temple where Dagoth's horn is kept, and this gives the filmmakers time to put us through long, gruelling dialogue and 'comic relief' regarding Jehnna's crush on Conan. That slack second half is in precise contrast to Conan the Barbarian, which accomplished its bumbling early on and then gained steam.

Conan the Destroyer feels less like the 1982 film than its knock-offs because, of course, it was penned by knock-off writers. No, not screenwriter Stanley Mann of Damien: Omen II, Firestarter and little else, but the duo who developed the story, Roy Thomas and Gerry Conway, who'd previously churned out the animated sword-and-sandal picture Fire and Ice and, in Thomas's case, worked on the television series Thundarr the Barbarian. Their work is inferior to that of John Milius and Oliver Stone in the original film in every respect, but let's start with the villains. Conan the Barbarian had Thulsa Doom, a terrific baddie played to perfection by James Earl Jones. In Destroyer, our heroes are menaced by this guy:

He turns into this when he wants to be extra-terrifying:

Need I say more?

Did Thomas & Conway - or anyone else, for that matter - really leave Conan the Barbarian thinking, 'This was pretty cool, but I wish Conan talked more/had a bunch of sidekicks/made more jokes?' Dino de Laurentiis apparently thought the first film's box office take had been hurt by its R rating, and subsequently worked hard to make Destroyer PG-13 by removing the nudity and gore of the original, but that's not where the problem lies. That would be sticking Conan into a tedious, padded story with limited personal stakes (no real effort is made to convince us of Conan's desire to bring Valeria back), and the sidekicks.

Ah yes! For this film replaces the mostly silent trio of the original (Conan, Subotai, Valeria) with, well, a party. It really does feel like a particularly unimaginative role-playing campaign, although at least they don't all meet in an inn. There are scenes that feel particularly Dungeons & Dragons: the ape-man at Toth-Amon's castle, for example, who can only be defeated by smashing all the mirrors in the room.

Mako as the wizard Akiro is a welcome presence, as is Wilt Chamberlain's Bombaata. I'm on the fence about Grace Jones as Zula: she's awesome, but her archetype - the savage warrior woman - is pretty racist, especially when contrasted with the exceedingly Aryan princess Jehnna. Malak, however, is perhaps the most wretched comic relief character before Jar Jar Binks. Tracey Walter, who's since carved out a very respectable career on television, is visibly miserable and unconvinced by the role. No-one could blame him: it isn't easy for actors to find work. Blame, instead, falls once more to Thomas & Conway, who should have remembered that comic relief is generally intended to be funny (hence 'comic').

Undone by an awful, meandering script, Conan the Destroyer holds up pretty well in other departments. Richard Fleischer, director of The Vikings and other sword-and-sandal pictures of the 1950s and 1960s, does his best to make the film no more boring than it has to be, and he's helped by the director of photography, fellow Vikings alumnus Jack Cardiff (who also shot the 1951 Bogart-Hepburn classic The African Queen). There is, in fact, a whiff of a last hurrah for the old guard surrounding Conan the Destroyer: the sword-and-sandal film of a previous generation going down in a blaze of sleepy non-glory. But in any case, they go down with some honestly pretty pictures:

Conan the Destroyer's budget was less than Barbarian's, and it seems more than once that being unable to afford something like the first film's majestic Mountain of Power they settled for a bunch of people bumbling around cheap-looking sets. But again, it's the fault of the writers who decreed that there must be crystal castles and temples covered in runes. In truth, Pier Luigi Basile's production design is good, great in the case of Queen Taramis's impressive throne room; and the same goes for the costumes, although there are some unconvincing wigs.

The single most disappointing aspect of the whole affair is that composer Basil Poledouris apparently zoned out. Poledouris's score for Conan the Barbarian has become a classic in its own right, but his work on the sequel is just tired. When he isn't plagiarising himself - the music from Barbarian's human soup scene is recycled for Destroyer's offering to Dagoth - it's just decidedly less exciting. Where Barbarian's music screamed epic!, the Destroyer score mutters, 'I was made for Saturday afternoon reruns'.

It's as if they went out of their way to remind the audience that Barbarian was a better film. When Malak says, and I'm quoting from memory here, 'LOOK, CONAN, IT'S A CAMEL, JUST LIKE THE ONE YOU PUNCHED IN THE FACE IN CONAN THE BARBARIAN' it would just be a clunky continuity nod - were it not for the fact that, being kicked off by a character not present in the original film, the scene suggests Conan boasts of his ignoble history of animal abuse to his companions.

If ever the title of a film improved upon Conan the Barbarian, surely it was Conan the Destroyer; but alas, reality proves otherwise. Not only does the promised destruction fail to ensue, we still don't learn how Conan became a king by his own hand, let alone what manner of crown he wore upon a troubled brow. The film's thorough failure is perhaps best summed up when Queen Taramis says,'What is there, Conan? Think!', and her suggestion does not strike us as self-evidently ridiculous. As for Thomas & Conway: fine writers you are - go back to juggling apples.

In this series: Conan the Barbarian (1982) | Conan the Destroyer (1984) | Red Sonja (1985) | Conan the Barbarian (2011)

Tuesday, 7 February 2012

Let me tell you of the days of high adventure

Thirty years on, 1982 self-evidently appears as a peak of genre cinema. What other year, after all, saw a slate that included the likes of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Tron, Blade Runner, First Blood and The Thing? As in any age, few of these masterpieces were recognised as such at the time: not every film could rake in the cash and critical accolades like E.T.: The Extraterrestrial.

None of those films would affect the world quite the way a certain sword-and-sorcery picture would, though. Conan the Barbarian put an Austrian bodybuilder on the road to running the world's eighth largest economy and being the only voice of reason in the Republican Party, and it did so by putting him into a leather loincloth. It's not just Schwarzenegger that got a career boost out of Conan, though; for while it's an exaggeration to say the film put Oliver Stone on the map, there might well have been no Platoon without it.

In the interests of full disclosure I must admit that Conan the Barbarian is one of my favourite films in the world, its heady mix of great and bafflingly awful unmatched in cinema otherwise. What other film aspires to such lofty excellence in some aspects while plumbing the depths of incompetence in others? It was for this reason that I found the 2011 remake so dispiriting. It was just bad, but in none of the gonzo inspired ways of its hallowed predecessor.

Conan (Arnold Schwarzenegger as an adult, Jorge Sanz as a boy) is raised by a tribe of Cimmerians who worship Crom, the god of steel. One day, his village is overrun by the forces of sinister warlord Thulsa Doom (James Earl Jones), who murder his parents (William Smith and Nadiuska, an Italian softcore actress). The tribe's children are put to slave labour pushing a giant wheel in the middle of nowhere. Over time the other children die from starvation and hard labour, and Conan alone grows into ridiculously muscular adulthood.

Eventually, he is trained to fight as a gladiator and becomes a champion in the arena. After being set free by his owner, Conan begins to search for Thulsa Doom. He's pointed in the right direction by a witch (Cassandra Gaviola) who subsequently transforms into a monster and attacks him during sex. Conan teams up with the thief Subotai (Gerry Lopez) and the warrior woman Valeria (Sandahl Bergman), and they're hired by King Osric (Max von Sydow) to retrieve his daughter, who has fallen in with a doomsday cult led by Doom.

The first half of the script is littered with plot holes and baffling non-sequiturs. Why did Thulsa Doom attack Conan's village? What purpose does the massy wheel of toil serve? Why was Conan freed? What's up with the witch? In several instances the voiceover narrator openly confesses his ignorance ('Who knows what they came for?'). Before growing tauter in the second half - when Conan and his crew infiltrate Thulsa Doom's cult at his Mountain of Power -, the story consists of no more than a succession of bizarre and hilarious incidents (Conan finds a sword after stumbling and falling into a cave! Conan punches a camel! Conan exclaims 'Crom!' at random intervals for no discernible reason!)

There's just a lot of weirdness in Conan the Barbarian, things that are not so much bad as totally puzzling. It's compulsively watchable in a so-bad-it's-good way. Take the odd scene in which Conan and Subotai earnestly discuss fictional theology by a campfire, or the mere fact that our hero does not speak at all until twenty-four minutes into the film. Perhaps the intention is to avoid drawing undue attention to Schwarzenegger's thick Teutonic accent, but it doesn't work too well. This, for example, is how Conan and Valeria first meet, while breaking into one of Doom's temples:

James Earl Jones seems to be in a different film altogether. His portrayal of a warlord turned charismatic cult leader is absolutely compelling, and the scene in which he demonstrates to Conan that 'flesh' (owning hearts and minds) is more powerful than steel is easily the film's best in an unironic way. Jones's amazing performance leads us straight into the plus column, and to the film's most important asset: it looks great.

Yes, Conan the Barbarian had one heck of a budget, and director John Milius splashes every last penny on the screen. The production design is lush, with pretty great costumes - even though Doom's Viking henchmen look oddly like early-eighties metal musicians, with Thorgrim in particular a dead ringer for Iron Maiden's Dave Murray. Duke Callaghan's landscape photography is terrific and atmospheric: heroic is the word I'm looking for, and the same goes for Basil Poledouris's rousing score.

That, then, is the enigma of Conan the Barbarian: it is one part so-bad-it's-good, a laughably acted random events plot; and a second part - the thrilling fight scenes, the production values, the music, James Earl Jones - genuinely great. These halves cannot be separated: they exist together in every scene of the film, and in John Milius's earnest vision they belong together. Conan's idea of a good time is 'to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentation of their women', and that is what Milius genuinely believed. If that ideology is wrongheaded, even contemptible, it nonetheless led to a maddening, baffling, and oddly endearing film.

In this series: Conan the Barbarian (1982) | Conan the Destroyer (1984) | Red Sonja (1985) | Conan the Barbarian (2011)

None of those films would affect the world quite the way a certain sword-and-sorcery picture would, though. Conan the Barbarian put an Austrian bodybuilder on the road to running the world's eighth largest economy and being the only voice of reason in the Republican Party, and it did so by putting him into a leather loincloth. It's not just Schwarzenegger that got a career boost out of Conan, though; for while it's an exaggeration to say the film put Oliver Stone on the map, there might well have been no Platoon without it.

In the interests of full disclosure I must admit that Conan the Barbarian is one of my favourite films in the world, its heady mix of great and bafflingly awful unmatched in cinema otherwise. What other film aspires to such lofty excellence in some aspects while plumbing the depths of incompetence in others? It was for this reason that I found the 2011 remake so dispiriting. It was just bad, but in none of the gonzo inspired ways of its hallowed predecessor.

Conan (Arnold Schwarzenegger as an adult, Jorge Sanz as a boy) is raised by a tribe of Cimmerians who worship Crom, the god of steel. One day, his village is overrun by the forces of sinister warlord Thulsa Doom (James Earl Jones), who murder his parents (William Smith and Nadiuska, an Italian softcore actress). The tribe's children are put to slave labour pushing a giant wheel in the middle of nowhere. Over time the other children die from starvation and hard labour, and Conan alone grows into ridiculously muscular adulthood.

Eventually, he is trained to fight as a gladiator and becomes a champion in the arena. After being set free by his owner, Conan begins to search for Thulsa Doom. He's pointed in the right direction by a witch (Cassandra Gaviola) who subsequently transforms into a monster and attacks him during sex. Conan teams up with the thief Subotai (Gerry Lopez) and the warrior woman Valeria (Sandahl Bergman), and they're hired by King Osric (Max von Sydow) to retrieve his daughter, who has fallen in with a doomsday cult led by Doom.

The first half of the script is littered with plot holes and baffling non-sequiturs. Why did Thulsa Doom attack Conan's village? What purpose does the massy wheel of toil serve? Why was Conan freed? What's up with the witch? In several instances the voiceover narrator openly confesses his ignorance ('Who knows what they came for?'). Before growing tauter in the second half - when Conan and his crew infiltrate Thulsa Doom's cult at his Mountain of Power -, the story consists of no more than a succession of bizarre and hilarious incidents (Conan finds a sword after stumbling and falling into a cave! Conan punches a camel! Conan exclaims 'Crom!' at random intervals for no discernible reason!)

There's just a lot of weirdness in Conan the Barbarian, things that are not so much bad as totally puzzling. It's compulsively watchable in a so-bad-it's-good way. Take the odd scene in which Conan and Subotai earnestly discuss fictional theology by a campfire, or the mere fact that our hero does not speak at all until twenty-four minutes into the film. Perhaps the intention is to avoid drawing undue attention to Schwarzenegger's thick Teutonic accent, but it doesn't work too well. This, for example, is how Conan and Valeria first meet, while breaking into one of Doom's temples:

CONAN: You are not a guard.This is how Conan meets his one true love (although, tellingly, Valeria isn't named until the credits). More or less all human interactions are howlingly incompetent. Schwarzenegger is perfectly cast in his total inability to act, giving us the sort of convincing performance as a barbarian Jason Momoa never could. He does get a couple of good lines: 'What do you see?', he is asked while peering into a fountain disguised as a priest, and he replies, 'Er... infinity'. Max von Sydow also makes the most of his cameo by chewing on the terrific line 'What daring! What outrageousness! What insolence! What arrogance!... I salute you.'

VALERIA: Neither are you. [...] Do you know what horrors lie beyond that wall?

CONAN: No.

James Earl Jones seems to be in a different film altogether. His portrayal of a warlord turned charismatic cult leader is absolutely compelling, and the scene in which he demonstrates to Conan that 'flesh' (owning hearts and minds) is more powerful than steel is easily the film's best in an unironic way. Jones's amazing performance leads us straight into the plus column, and to the film's most important asset: it looks great.

Yes, Conan the Barbarian had one heck of a budget, and director John Milius splashes every last penny on the screen. The production design is lush, with pretty great costumes - even though Doom's Viking henchmen look oddly like early-eighties metal musicians, with Thorgrim in particular a dead ringer for Iron Maiden's Dave Murray. Duke Callaghan's landscape photography is terrific and atmospheric: heroic is the word I'm looking for, and the same goes for Basil Poledouris's rousing score.

That, then, is the enigma of Conan the Barbarian: it is one part so-bad-it's-good, a laughably acted random events plot; and a second part - the thrilling fight scenes, the production values, the music, James Earl Jones - genuinely great. These halves cannot be separated: they exist together in every scene of the film, and in John Milius's earnest vision they belong together. Conan's idea of a good time is 'to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentation of their women', and that is what Milius genuinely believed. If that ideology is wrongheaded, even contemptible, it nonetheless led to a maddening, baffling, and oddly endearing film.

In this series: Conan the Barbarian (1982) | Conan the Destroyer (1984) | Red Sonja (1985) | Conan the Barbarian (2011)

Tuesday, 24 January 2012

Just Roman around

The ancient epic revived by Gladiator collapsed under its own weight after Alexander, Troy and Kingdom of Heaven bored, bothered and bewildered audiences in 2004-5. It's no coincidence that semi-legendary director Ridley Scott should have been the genre's father as well as its gravedigger: at its height it attracted talent and money of a kind otherwise only seen in comic-book adaptations.

To all appearances the ancient epic was dead, but green shoots soon appeared. 300 proved that classical antiquity could still sell tickets, and the film's basic ingredients - a middling budget, a relatively junior director, over-the-top masculinity - became the building blocks of the revived revived classical picture. No longer epics but mid-range action-adventure flicks, films like Pathfinder, Clash of the Titans and Conan the Barbarian have not yet stopped making money.

Excepting 300, there hasn't yet been a single good film in the subgenre. Sadly Centurion proves no exception to this rule, but the film's thorough failure is especially frustrating considering its potential. Let's quickly run through the factors that ought to make Centurion utterly awesome. It was directed by Neil Marshall, he of The Descent (which, to my enduring shame, I haven't seen); it stars a post-Hunger Michael Fassbender, one of the greatest actors on this earth, as well as Dominic West of The Wire; it's set along the spectacular Caledonian frontier of Roman Britain; and oh yeah, there's the little matter of Olga Kurylenko wearing warpaint. But instead of being great or even diverting, Centurion just flails around wasting its potential for an hour and a half, and then ends.

We open with credits, and what ugly credits they are! As we're treated to a long aerial shot of Scottish mountains (beautiful in themselves), the credits woosh towards us in the most aggressive way possible; and if you like hideous fonts you're in luck, because the monstrosity in which everyone's name is presented will later double as subtitles for the Picts' barbarian tongue. My jaw dropped at the sheer atonal artlessness of this sequence: it looks like a computer game trailer from 1996, and I first assumed Centurion must be designed to be viewed in 3D like those early 80s films in which the credits seem out to stab you in the eye. But no, it's all two dimensions.

Anyway, we now get a shot of a half-naked man running through the snow-covered Caledonian wilderness, hunted by barbarians; in voiceover, he introduces himself as Quintus Dias, a Roman centurion. And with that we're back to sometime earlier, when Dias's fort is overrun in a Pictish surprise attack, all the soldiers are killed and Dias himself is captured and brought before the Pictish king Gorlacon (Ulrich Thomsen). Some heated words are exchanged, and then Dias escapes offscreen. Got all that? Don't worry if not: everything I've just told you is irrelevant, and any information contained therein will shortly be repeated.

Anyway, Marshall cuts away to York, where General Titus Flavius Virilus (Dominic West) is ordered to take his Ninth Legion north of the border and defeat Gorlacon. He's assigned the mute British scout Etain (Olga Kurylenko) to guide him north of the border. During the expedition, Virilus saves the still-fleeing Dias from the Picts. The cheerful camaraderie does not last long, for like you and I Neil Marshall saw The Last of the Mohicans, wherefore Etain leads the Romans into an ambush where they're slaughtered by theHuron Picts. (On the plus side, West gets to shout 'It's a trap!'.)

All, that is, except for Dias himself and a ragtag bunch of misfit soldiers including Brick (Liam Cunningham). Dias leads these survivors to save their captured general, but their rescue operation is a fiasco: not only do they fail to rescue Virilus, but one of the Roman soldiers kills Gorlacon's son, leading the enraged Pict to swear blood vengeance on the fleeing legionaries. Before long, they're pursued across the harsh mountains of Caledonia by a posse led by the wrathful Etain.

Centurion's most crippling flaw is the absolutely wretched script, penned by Marshall himself. Let's not dwell for too long on the fact that it's relentlessly derivative, playing like a wacky mash-up of The Last of the Mohicans, Apocalypto, and Cold Mountain; nor will it do much good to groan at the plot holes, or the awkward way in which the mysterious disapperance of the Ninth is shoehorned in at the end. (And by 'mysterious disappearance', we of course mean 'failure to appear in the very patchy extant documents we have, although many of its officers do turn up in various places').

No, let's focus on the stuff that leaves the actors stranded. Fassbender's character, for example, has a backstory (his father was a gladiator) that's referred to exactly once and never impacts the plot; most other characters are not granted even that luxury. (Kurylenko gets an origin that opens the film's largest, most amusing plot hole.) As a result, Marshall is guilty of criminal negligence in wasting a very capable cast: I hesitate to use a phrase like 'career-worst performances all round', but anyone who's seen that already legendary dialogue scene between Fassbender and Cunningham in Hunger can only weep.

Surprisingly, Marshall's direction isn't much better than his script. He's so keen on Dutch angles one might think he was filming a Bizarro-World prequel to Battlefield Earth. His action scenes are best described as uninspired (they're shot and edited in the same choppy, disorienting way we see everywhere now). There is a stunningly tasteless zoom shot of Kurylenko screaming that lovingly shows off her tongueless mouth, too; and while this is a low point, it's not alone in this film.

The historical inaccuracies I complain about, but I can live with: I liked Gladiator, after all. I like the fact that the Picts are speaking Scottish Gaelic (although Arianne, played by Imogen Poots, goes for broad Scottish-accented English instead). Sure, it's not quite right: no-one knows for certain whether the Picts spoke a Celtic language, and if they did it was probably more closely related to the Brythonic languages of southern Britain rather than the Goidelic languages of Ireland and Dal Riada - from which Scottish Gaelic is descended - but I appreciate the effort.

That Roman soldiers in films forever use their gladii to slash away at their opponents, rather than viciously stab them in the gut as they should, is by now expected; that the Roman soldiers carry the wrong spears - hastae, thrusting spears used both in the early Republic and in the late Empire, rather than pila, heavy javelins - surprised me a little, but I'll take it as a bold attempt to draw attention to the fact that Roman equipment was not uniform throughout the empire. And I rather adore the film's earthy tone and the use of English regional accents to represent Vulgar Latin.

My tone has, I think, been somewhat harsher than Centurion really deserves: it's not totally incompetent. As a dully entertaining genre flick, it mostly works. The problem is that it's such a disappointment: filmed in the absolutely gorgeous outdoors of Scotland and northern England, the film should look amazing, but cinematographer Sam McCurdy can't hack it. Instead, its wintry landscapes quote the visual vocabulary of King Arthur, surely the most dire film ever made on similar subject matter. Its other flaws - strange fade cuts, the gruff growling that seems to be mandatory for male actors in these films - are forgivable; what makes Centurion especially appalling is the sheer sad, ruinous waste of talent and opportunity it presents.

To all appearances the ancient epic was dead, but green shoots soon appeared. 300 proved that classical antiquity could still sell tickets, and the film's basic ingredients - a middling budget, a relatively junior director, over-the-top masculinity - became the building blocks of the revived revived classical picture. No longer epics but mid-range action-adventure flicks, films like Pathfinder, Clash of the Titans and Conan the Barbarian have not yet stopped making money.

Excepting 300, there hasn't yet been a single good film in the subgenre. Sadly Centurion proves no exception to this rule, but the film's thorough failure is especially frustrating considering its potential. Let's quickly run through the factors that ought to make Centurion utterly awesome. It was directed by Neil Marshall, he of The Descent (which, to my enduring shame, I haven't seen); it stars a post-Hunger Michael Fassbender, one of the greatest actors on this earth, as well as Dominic West of The Wire; it's set along the spectacular Caledonian frontier of Roman Britain; and oh yeah, there's the little matter of Olga Kurylenko wearing warpaint. But instead of being great or even diverting, Centurion just flails around wasting its potential for an hour and a half, and then ends.

We open with credits, and what ugly credits they are! As we're treated to a long aerial shot of Scottish mountains (beautiful in themselves), the credits woosh towards us in the most aggressive way possible; and if you like hideous fonts you're in luck, because the monstrosity in which everyone's name is presented will later double as subtitles for the Picts' barbarian tongue. My jaw dropped at the sheer atonal artlessness of this sequence: it looks like a computer game trailer from 1996, and I first assumed Centurion must be designed to be viewed in 3D like those early 80s films in which the credits seem out to stab you in the eye. But no, it's all two dimensions.

Anyway, we now get a shot of a half-naked man running through the snow-covered Caledonian wilderness, hunted by barbarians; in voiceover, he introduces himself as Quintus Dias, a Roman centurion. And with that we're back to sometime earlier, when Dias's fort is overrun in a Pictish surprise attack, all the soldiers are killed and Dias himself is captured and brought before the Pictish king Gorlacon (Ulrich Thomsen). Some heated words are exchanged, and then Dias escapes offscreen. Got all that? Don't worry if not: everything I've just told you is irrelevant, and any information contained therein will shortly be repeated.

Anyway, Marshall cuts away to York, where General Titus Flavius Virilus (Dominic West) is ordered to take his Ninth Legion north of the border and defeat Gorlacon. He's assigned the mute British scout Etain (Olga Kurylenko) to guide him north of the border. During the expedition, Virilus saves the still-fleeing Dias from the Picts. The cheerful camaraderie does not last long, for like you and I Neil Marshall saw The Last of the Mohicans, wherefore Etain leads the Romans into an ambush where they're slaughtered by the

All, that is, except for Dias himself and a ragtag bunch of misfit soldiers including Brick (Liam Cunningham). Dias leads these survivors to save their captured general, but their rescue operation is a fiasco: not only do they fail to rescue Virilus, but one of the Roman soldiers kills Gorlacon's son, leading the enraged Pict to swear blood vengeance on the fleeing legionaries. Before long, they're pursued across the harsh mountains of Caledonia by a posse led by the wrathful Etain.

Centurion's most crippling flaw is the absolutely wretched script, penned by Marshall himself. Let's not dwell for too long on the fact that it's relentlessly derivative, playing like a wacky mash-up of The Last of the Mohicans, Apocalypto, and Cold Mountain; nor will it do much good to groan at the plot holes, or the awkward way in which the mysterious disapperance of the Ninth is shoehorned in at the end. (And by 'mysterious disappearance', we of course mean 'failure to appear in the very patchy extant documents we have, although many of its officers do turn up in various places').

No, let's focus on the stuff that leaves the actors stranded. Fassbender's character, for example, has a backstory (his father was a gladiator) that's referred to exactly once and never impacts the plot; most other characters are not granted even that luxury. (Kurylenko gets an origin that opens the film's largest, most amusing plot hole.) As a result, Marshall is guilty of criminal negligence in wasting a very capable cast: I hesitate to use a phrase like 'career-worst performances all round', but anyone who's seen that already legendary dialogue scene between Fassbender and Cunningham in Hunger can only weep.

Surprisingly, Marshall's direction isn't much better than his script. He's so keen on Dutch angles one might think he was filming a Bizarro-World prequel to Battlefield Earth. His action scenes are best described as uninspired (they're shot and edited in the same choppy, disorienting way we see everywhere now). There is a stunningly tasteless zoom shot of Kurylenko screaming that lovingly shows off her tongueless mouth, too; and while this is a low point, it's not alone in this film.

The historical inaccuracies I complain about, but I can live with: I liked Gladiator, after all. I like the fact that the Picts are speaking Scottish Gaelic (although Arianne, played by Imogen Poots, goes for broad Scottish-accented English instead). Sure, it's not quite right: no-one knows for certain whether the Picts spoke a Celtic language, and if they did it was probably more closely related to the Brythonic languages of southern Britain rather than the Goidelic languages of Ireland and Dal Riada - from which Scottish Gaelic is descended - but I appreciate the effort.

That Roman soldiers in films forever use their gladii to slash away at their opponents, rather than viciously stab them in the gut as they should, is by now expected; that the Roman soldiers carry the wrong spears - hastae, thrusting spears used both in the early Republic and in the late Empire, rather than pila, heavy javelins - surprised me a little, but I'll take it as a bold attempt to draw attention to the fact that Roman equipment was not uniform throughout the empire. And I rather adore the film's earthy tone and the use of English regional accents to represent Vulgar Latin.

My tone has, I think, been somewhat harsher than Centurion really deserves: it's not totally incompetent. As a dully entertaining genre flick, it mostly works. The problem is that it's such a disappointment: filmed in the absolutely gorgeous outdoors of Scotland and northern England, the film should look amazing, but cinematographer Sam McCurdy can't hack it. Instead, its wintry landscapes quote the visual vocabulary of King Arthur, surely the most dire film ever made on similar subject matter. Its other flaws - strange fade cuts, the gruff growling that seems to be mandatory for male actors in these films - are forgivable; what makes Centurion especially appalling is the sheer sad, ruinous waste of talent and opportunity it presents.

Saturday, 31 December 2011

Class and class struggle in early Rome

Despite its grandiose title, this post - long delayed by being away from my copy of Livy's Ab urbe condita - does not offer an outline of class struggle in the early Roman Republic as a whole. It is intended, instead, to provide a brief introduction to how Livy frames conflict between the orders. (This is based on The Early History of Rome, the Penguin translation of the first five books of Ab urbe condita, which ends with the sack of Rome by the Gauls.)

The early Republic was a Beutegemeinschaft, a society based on capturing and distributing loot through annual warfare. Success in war kept the gold flowing and was thus integral to the survival of the state, which exported its tensions. For this, the patricians - Rome's ancient aristocracy, the political and religious elite - required the consent of the far larger plebeian class, who did most of the fighting.

This was exploited by the plebeians in the first secessio plebis in 494 BC - a general strike in which the plebeians, rather than respond to military summons, left the city, gathered on the Mons Sacer and threatened to found a new town. Grievances included disadvantages in the allocation of land in colonies, armed Roman settlements built to subdue captured enemy territory, and the patricians' exclusive privileges. The patricians made significant concessions, including the institution of plebeian tribunes, representatives of the plebs who could influence the legislative process. The ongoing tug-of-war between the tribunes and the Senate occupies much of Livy's account.

Most of what we learnt in school, though, was about Rome's foreign wars, not her internal struggles. This is hardly surprising, since the conflict of the orders offers none of the dramatic bloodletting of Porsena's siege of Rome or the wars against Veii; but in truth the social conflict, mostly confined to forums and laws though it is, provides thrills aplenty. It also has the advantage of being less overgrown with fictions and the rigid narrative framework all accounts of foreign wars had to follow.

Livy includes a beautiful vignette that encapsulates the patricians' fears at the opening of his fourth book. Faced with the prospect of a bill brought by the plebeians that would legalise intermarriage between the orders - an unthinkable travesty to the aristocracy - the consuls M. Genucius and C. Curtius respond (4.1):

In all communities the qualities or tendencies which carry the highest reward are bound to be most in evidence and to be most industriously cultivated - indeed it is precisely that which produces good statesmen and good soldiers; unhappily here in Rome the greatest rewards come from political upheavals and revolt against the government, which have always, in consequence, won applause from all and sundry. Only recall the aura of majesty which surrounded the Senate in our father's day, and then think what it will be like when we bequeath it to our children! Think how the labouring class will be able to brag of the increase in its power and influence! There can never be an end to this unhappy process so long as the promoters of sedition against the government are honoured in proportion to their success. Do you realise, gentlemen, the appalling consequences of what Canuleius is trying to do? If he succeeds, bent, as he is, upon leaving nothing in its original soundness and purity, he will contaminate the blood of the ancient and noble families and make chaos of the hereditary patrician privilege od 'taking the auspices' to determine, in the public or private interest, what Heaven may will - and with what result? that, when all distinctions are obliterated, no one will know who he is or where he came from! Mixed marriages forsooth! What do they mean but that men and women from all ranks of society will be permitted to start copulating like animals? A child of such intercourse will never know what blood runs in his veins or what form of worship he is entitled to practise; he will be nothing - or six of one and half a dozen of the other, a very monster!We're not supposed to like these consuls (whose speech, of course, is fabricated wholecloth by Livy). The points made, though, are familiar: the belief that rampant disobedience to authority is crippling the commonwealth, as the Tories affirm; the notion that society, politically correct as it is, rewards the lazy and insubordinate; and lastly, a fear of what, in a different day and age, the Americans called miscegenation, which will lead to human beings becoming as beasts. There's nothing more heartening than reading millennia-old rants warning of the imminent collapse of human civilisation - it puts the Daily Heil in perspective.

We might call Livy's stance on all this broadly call patriotic: he firmly disapproves of internal strife that weakens Rome against her enemies. To this end, he demands justice for the plebeians and repeatedly censures the more arrogant of the patricians: but he also wishes the plebeians would cease to cause trouble. That Livy's narrative should be dominated by his desire for internal peace is hardly surprising. He was writing towards the end of the first century BC, when the period of vicious and hugely destructive civil wars - still within living memory - had ended with the dominance of Augustus, who is praised for restoring concord (even as Livy holds modern morals to be depraved).