The Empire Strikes Back (1980) started a Star Wars tradition of confusing and alienating audiences that has become pretty much synonymous with the franchise over the years. For despite being advertised by just that four-word title ahead of release (see the poster), the film's opening crawl instead referred to it as Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back. A science-fiction franchise had suddenly become a humongous 'saga' that had apparently and inexplicably begun on its fourth installment. The course had been set for a bright future of crippling continuity errors and, eventually, a leaden prequel trilogy - a curious achievement for what is clearly and unequivocally the best film in the series.

This doesn't quite seem to have been the intention right at the start: some of the most distinctive plot elements of Empire (SPOILERS) were only introduced by George Lucas after he was disappointed by a first draft, written by veteran space opera and planetary romance writer Leigh Brackett in the final stages of her battle with cancer. In reworking the script Lucas came up with the film's darker direction and the no-longer-stunning plot twist that Darth Vader is (well, claims to be, as far as Empire is concerned) Luke Skywalker's father. This in turn led to a backstory expansion in which Anakin Skywalker was Obi-Wan Kenobi's apprentice before being seduced by the Emperor (now a user of the dark side of the Force and no longer a mere politician, though not yet Ian McDiarmid), opening the possibility of a prequel trilogy. This newer, bigger story also retroactively turned Obi-Wan into a liar who manipulated Luke into helping him and attempting to blow up his own father along with the Death Star, but really, in the continuity mess of even the core Star Wars canon that's small change.

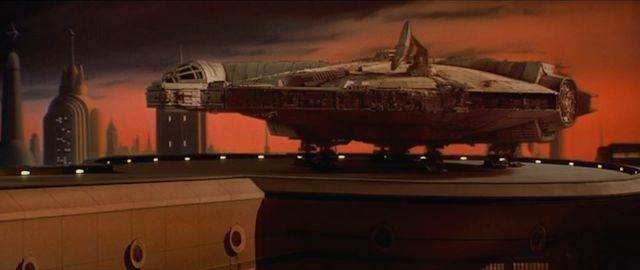

The story: forces of the Rebel Alliance, including all the surviving

heroes of the previous film, have constructed a base on the inhospitable

ice world of Hoth. Before long, though, they're discovered by the

Imperial fleet of Darth Vader. The rebels manage to hold off the

Imperial ground assault long enough to pull off a successful withdrawal

but Han Solo and Leia Organa (Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher) fail to

get away from the Imperials because of the Millennium Falcon's broken

hyperdrive. Hiding first in a deadly asteroid field and then fleeing to

Cloud City, where Han's old frenemy Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee

Williams) runs a mining operation, they're hunted by Vader's fleet as

well as a bunch of bounty hunters.

Meanwhile, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) follows a vision of his one-time mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi to the swamp world of Dagobah. There, Obi-Wan's own teacher, the diminutive and ancient Jedi master Yoda (Frank Oz), instructs him in the ways of the Force, teaching him to become a Jedi knight himself. Before he can complete his training, though, Luke has a premonition of his friends in danger. Worried by Yoda's warnings but ultimately unable to ignore Han and Leia's suffering, Luke races off to Cloud City, his training unfinished, to save his friends from Vader's clutches.

The final script, written by Lawrence Kasdan based on Lucas's second

draft, is fantastic: it zips by, the necessary exposition is handled

supremely well (for a film that expands the story so much, there are

very few scenes of character simply sitting down and talking), and the

dialogue is much punchier and more contemporary than Lucas's

self-conscious throwback pulp stylings in Star Wars. Those work too, and having lavished praise on Lucas's script I'm not about to change my mind. But what worked for Star Wars wouldn't work for Empire:

where the first film was all about roughly sketching a world of

intergalactic adventure and a stark battle between good and evil, the

second installment fleshes out that world and develops its characters

from old-school sci-fi archetypes into, well, people.

(Even so, let's not beat about the bush: the timeline of Empire is pretty much impossible (which isn't to say Star Wars

fans haven't made up elaborate excuses for the film). In the time that

Han and Leia take to run from Hoth to Bespin, the Empire hot on their

heels (a few standard days at most), Luke goes to Dagobah, meets Yoda

and gets a significant chunk of Jedi training done (weeks at least).

Impossible in terms of realism, to be sure. But in story terms, it

works: Luke's less action-packed, more contemplative and philosophical

scenes alternate effectively with scenes of danger involving Han and

Leia. Time has always moved at the speed of plot in Star Wars, and I'm

happy to give the film a pass here.)

The new and improved dialogue does a lot for the characters, and it's a much better fit for some of the actors. Carrie Fisher's Leia is even more acerbic this time around, and Kasdan gives her a couple of fantastic zingers: 'Would it help if I got out and pushed?' when Han's rust bucket won't get going, or the wondrous 'You don't have to do this to impress me' as he heads into an asteroid field. That brings us neatly to the problem of Leia in Empire: she's reduced from the aristocratic leader of Star Wars to playing the straight man to Han Solo's antics. Which is enjoyable, but leaves the character a little thin. Ford is freer and looser this time around (thanks, no doubt, to a more cooperative director), and Hamill is - well, I like him less in Empire than in either Star Wars or Jedi, but his final scenes in the film are terrific, no doubt about it.

In the smaller roles there's so much goodness: I'm a particular fan of

all the pitiable Imperial officers who must achieve impossible

objectives, or be murdered by Vader. (There is, in general, a lot of

excellent bleak humour in the scenes aboard the Executor). An

easy favourite is Kenneth Colley's put-upon Admiral Piett, a man who

through long practice has become really good at ignoring people being

force-choked right next to him, and actually makes it out of Empire alive.

But Julian Glover's General Veers, a man who clearly enjoys nothing

more than (a) sneering and (b) stomping on infantry with his enormous

armoured tank, is a wonderful mini-villain too. On the other side, I'm a

big fan of Bruce Boa's General Rieekan, who radiates a slightly gruff

but likeable authority on Hoth.

That's all well and good, but let's get to the best character in Empire, shall we? Because Yoda is that. I still love the reveal that the cackling imp who rummages through Luke's equipment is, in fact, a powerful Jedi master. He's a perfect embodiment of the film's thesis that the Force as a mystical ally can help the weak triumph over the strong, that it makes the underdog's victory over all the Empire's might a real possibility. He injects a warm sense of wonder about the Force, a humanist love of people over cold military power ('luminous beings are we, not this crude matter') and a yearning for peace ('wars not make one great'). And he does it all with humour (Frank Oz's outraged delivery of 'Mudhole? Slimy? My home this is!' cracks me up every time), dignity, and real authority. I understand that for Hamill weeks of sharing the scene with a puppet weren't too much fun, but the result is spellbinding.

(You know who sucks in Empire, though? Obi-Wan Kenobi. He does nothing but deliver some exposition and whinge about stuff. And Alec McGuinness, whose wry self-amusement worked wonders in Star Wars, is really phoning it in this time around. It's a waste.)

Lucas didn't do much to polish Empire in the special editions and home video releases. The major exception - one Star Wars fans don't object to, curiously - is Ian McDiarmid portraying the emperor (instead of Elaine Baker with digitally inserted chimpanzee eyes and Clive Revill doing the voice). Even better is that you don't need the despecialized edition to appreciate the special effects, which Lucas, despite his reputation, has only ever tweaked to remove errors. And they're wonderful. Terrifying stop-motion AT-ATs marching mercilessly across the frozen landscape while seemingly mosquito-sized rebel snowspeeders flit around them, a city floating above the clouds, a star destroyer adrift after a hit from the ion cannon. My absolute favourite, though, is the tauntauns. The puppet work in close-ups is very good, but I adore the stop-motion used in wide shots even more. The creatures move in an alien yet believable way, and they've got an almost Harryhausenesque amount of personality. (Plus great sound design, but in Star Wars that goes without saying.)

In the hands of Irvin Kershner Empire is a bit more life-sized than Star Wars, its characters just as mythical but a little less archetypal. By the second film, the series was starting to fill out its world, developing its characters (who are starting to feel like people we know and like instead of The Naive Young Hero, The Rogue, The Damsel, The Mentor, &c.) and breaking free from its '30s forebears. Put another way, Empire feels much less like Flash Gordon fan-fiction and much more like the work of people who suspected that more than just paying homage to them, Star Wars would utterly displace the pulp serials of yore in the public imagination. With a compelling story involving great characters, terrific setpieces and top-notch craftsmanship, Empire provides a good argument that Star Wars' place as a pop culture juggernaut is fully and legitimately earned.

Showing posts with label fantasy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fantasy. Show all posts

Wednesday, 18 November 2015

Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter

Saturday, 3 October 2015

Hokey religions and ancient weapons

Star Wars is the first blockbuster franchise I loved. Whether it was for lack of interest or because I preferred books, I didn't watch a lot of films when I was a kid. Star Wars blew me away. It opened up my imagination to a whole world of pulp science fantasy and started me off on a geeky obsession that has never gone away, attested to by shelves of tattered, treasured Expanded Universe novels.

Admittedly the Star Wars film I'm talking about was The Phantom Menace, and I only caught up with the first film in the series on VHS a few months later. I loved them both - I suppose I wasn't the most discriminating eleven-year-old. With time I learnt that fandom orthodoxy frowned on The Phantom Menace but loved Episode IV: A New Hope, as Lucas retitled the 1977 film on its re-release. And at least as far as Episode IV is concerned, the fandom is right. The film is ace: a total matinee delight that may not be the same technical marvel it appeared in 1977, but holds up just about perfectly all the same.

(A quick note: the basis for this review is the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars, a fan-made high-definition version of the original trilogy that attempts to restore the films as they originally appeared in cinemas, instead of the 1997 'special editions' (plus subsequent additions and changes) that modern Blu-ray copies are based on - fan-made because Lucas infamously wouldn't release anything except his new and allegedly improved versions in high-definition.

The thing is, the special editions are how I first experienced Star Wars, and I imagine it's the same for a lot of people who weren't around in the seventies and early eighties. But because of all the criticism the special editions get in fan circles - Han shot first et cetera ad nauseam - I was aware of most of the changes. They're pretty minor, by and large: CGI critters instead of practical effects, mostly, and a weird floating Jabba who pops in to utter the exact same threats Greedo did hardly five minutes earlier. But there's one exception: a scene near the end, in which Luke meets his old Tattooine mate Biggs Darklighter on Yavin 4, which ended up on the cutting room floor in the original release but was restored for the special editions. And considering the banter between the pilots during the Death Star attack is damn weird without that scene - they're talking as if they've known each other all their lives, which isn't indicated in anything we've seen before - restoring it was clearly the right decision.)

The story: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a nineteen-year-old living on the backwater planet of Tatooine, longs to be released from his tedious life on his uncle's moisture farm and go off to become a starfighter pilot. Tasked with cleaning two new droids his uncle has bought (Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker), Luke discovers they're carrying a message of vital importance from Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), which they're tasked with relaying to a retired general and current hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that just like himself, Luke's father was a Jedi Knight, a fighter for good drawing on the mystical Force killed by the evil Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), and perhaps Luke would like to accompany him to leave Tatooine and join Princess Leia in their rebellion against the evil Galactic Empire?

This is understandably too much for Luke to take in straight away, but his decision is made for him: Imperial stormtroopers attack his home, massacring his aunt and uncle and forcing Luke, Obi-Wan and the droids to flee. In the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, they hire smuggler Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his towering alien sidekick Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), who are themselves in a lot of trouble with some unsavoury elements. Together, this motley crew head to Leia's homeworld of Alderaan, only to find the whole planet obliterated by something that decidedly isn't any moon...

Everyone knows that story, but it's perhaps worth pointing out the ways in which the plot of the 1977 film isn't the story of the Star Wars franchise that developed after it, simply because George Lucas and his collaborators hadn't settled on those things yet. Certain family relationships don't yet exist; Obi-Wan unambiguously hates Vader's guts; the Jedi are treated as a myth of the ancient past and the existence of the Force is explicitly denied by several characters, although in the course of the film it seems to become the official creed of the Rebel Alliance; the emperor is a distant, unseen figure; Vader is only one of the empire's henchmen and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) orders him around, while others openly insult his religious beliefs.

It's so simple and archetypal (little wonder, since Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces): a wide-eyed audience stand-in who dreams of seeing something of the world, be a hero and rescue a beautiful princess; a wise old mentor, not long for this world; a charming rogue who learns to value friendship over money; a dastardly villain; and a character who, yes, is at this point still kind of an old-school damsel in distress, but at least has her own mind, some justifiable complaints about her ill-planned rescue, and ideas for how to do a better job. But it takes skill to do this stuff well, and Star Wars does it extremely well.

The script isn't usually given the amount of credit it's due, but it's among the reasons for the success of Star Wars and its immediate ability to capture the imagination. Lucas wrote the thing more than once, never happy with the results, and when Star Wars started filming in Tunisia the screenplay was still unfinished. The process of often sharply critical feedback over several years from Hollywood insiders and Lucas's wife, as well as uncredited dialogue rewrites by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, somehow produced a particular alchemy.

The result is glorious high pulp, instantly quotable and wonderful: "You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy"; "I find your lack of faith disturbing"; "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid"; "Evacuate? In our moment of triumph?"; "The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers", and so on. None of this is remotely how real people talk, but it gives the film an outsized air of adventure and wonder that helps it hit all the high notes.

Then there are the performances. The role of Luke Skywalker at this point is still something of a generic person, but Mark Hamill gets that right: we like and empathise with Luke, and that's what the film needs. The others are allowed to do more, and they're terrific. Alec Guinness forever seems gently amused at being asked to deliver dialogue about Jedi knights and disturbances in the Force, which results in a winning, light performance. Peter Cushing, veteran Hammer Horror vampire hunter, makes for a marvellously icy and authoritative warlord with drive, determination and cruelty to spare.

To me, there are three standouts: Harrison Ford's natural charisma causes him to make the role his own so much that he essentially spun it off into another franchise, as Indiana Jones. Anthony Daniels portrays C-3PO as a self-pitying but fundamentally decent comic foil who gets some of the film's biggest laughs ("Listen to them, they're dying, R2! Curse my metal body, I wasn't fast enough, it's all my fault!") And lastly, David Prowse's physical acting has always been overshadowed by James Earl Jones's voice, but his performance inside the Darth Vader suit is perfect: authoritative and menacing, but very far from emotionless. I adore the scene in which he pauses as he senses Obi-Wan for the first time; it's subtle but all kinds of wonderful.

Star Wars wouldn't be Star Wars without the lovely production design, though: it's chock-full of amazing ideas brilliantly executed. And unlike the second and third prequels, which are full of stuff happening in the background, the first film has the sense to actually briefly focus on the terrific alien suits, grime-covered droids and fossils bleached by the Tatooine suns, giving them each the dignity and two seconds of glory they deserve. (My favourite is and remains the tiny droid skittering away from Chewbacca on the Death Star, beeping in fear.) The film's used-future aesthetic - which belongs exclusively to the good and neutral characters, while the Empire is exquisitely glossy - is wonderfully and consistently realised.

The special effects are extremely good: they look dated, yes, but virtually never unconvincing. The real star is Ben Burtt's sound design, though. From all the mechanical whirring and hissing to Chewbacca's voice and Vader's breathing, the sounds of Star Wars remain instantly recognisable. There's so much high-class craftsmanship here, it really makes you appreciate the often-forgotten art of sound design (and miss it in all the projects that neglect to go beyond mere competence).

So what doesn't hold up? Despite everything, the final film is a bit slight; it zips past having established fairly little of its world beyond rough outlines, and selling some of its character development more through conviction than storytelling logic (Luke's attachment to Obi-Wan, in particular, feels dodgy after so short an acquaintance, especially since he immediately forgets about the people who raised him). The film offers a world of adventure so appealing, it's not surprising people wanted sequels and an enormous expanded universe. But it also feels a little like Star Wars needed those things to round it out, and like, had nothing else ever followed, the film would feel roughly sketched. But if the worst thing I can say about a film is that I want more of its world and characters than it can possibly provide in two hours, well...

Admittedly the Star Wars film I'm talking about was The Phantom Menace, and I only caught up with the first film in the series on VHS a few months later. I loved them both - I suppose I wasn't the most discriminating eleven-year-old. With time I learnt that fandom orthodoxy frowned on The Phantom Menace but loved Episode IV: A New Hope, as Lucas retitled the 1977 film on its re-release. And at least as far as Episode IV is concerned, the fandom is right. The film is ace: a total matinee delight that may not be the same technical marvel it appeared in 1977, but holds up just about perfectly all the same.

(A quick note: the basis for this review is the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars, a fan-made high-definition version of the original trilogy that attempts to restore the films as they originally appeared in cinemas, instead of the 1997 'special editions' (plus subsequent additions and changes) that modern Blu-ray copies are based on - fan-made because Lucas infamously wouldn't release anything except his new and allegedly improved versions in high-definition.

The thing is, the special editions are how I first experienced Star Wars, and I imagine it's the same for a lot of people who weren't around in the seventies and early eighties. But because of all the criticism the special editions get in fan circles - Han shot first et cetera ad nauseam - I was aware of most of the changes. They're pretty minor, by and large: CGI critters instead of practical effects, mostly, and a weird floating Jabba who pops in to utter the exact same threats Greedo did hardly five minutes earlier. But there's one exception: a scene near the end, in which Luke meets his old Tattooine mate Biggs Darklighter on Yavin 4, which ended up on the cutting room floor in the original release but was restored for the special editions. And considering the banter between the pilots during the Death Star attack is damn weird without that scene - they're talking as if they've known each other all their lives, which isn't indicated in anything we've seen before - restoring it was clearly the right decision.)

The story: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a nineteen-year-old living on the backwater planet of Tatooine, longs to be released from his tedious life on his uncle's moisture farm and go off to become a starfighter pilot. Tasked with cleaning two new droids his uncle has bought (Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker), Luke discovers they're carrying a message of vital importance from Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), which they're tasked with relaying to a retired general and current hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that just like himself, Luke's father was a Jedi Knight, a fighter for good drawing on the mystical Force killed by the evil Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), and perhaps Luke would like to accompany him to leave Tatooine and join Princess Leia in their rebellion against the evil Galactic Empire?

This is understandably too much for Luke to take in straight away, but his decision is made for him: Imperial stormtroopers attack his home, massacring his aunt and uncle and forcing Luke, Obi-Wan and the droids to flee. In the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, they hire smuggler Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his towering alien sidekick Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), who are themselves in a lot of trouble with some unsavoury elements. Together, this motley crew head to Leia's homeworld of Alderaan, only to find the whole planet obliterated by something that decidedly isn't any moon...

Everyone knows that story, but it's perhaps worth pointing out the ways in which the plot of the 1977 film isn't the story of the Star Wars franchise that developed after it, simply because George Lucas and his collaborators hadn't settled on those things yet. Certain family relationships don't yet exist; Obi-Wan unambiguously hates Vader's guts; the Jedi are treated as a myth of the ancient past and the existence of the Force is explicitly denied by several characters, although in the course of the film it seems to become the official creed of the Rebel Alliance; the emperor is a distant, unseen figure; Vader is only one of the empire's henchmen and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) orders him around, while others openly insult his religious beliefs.

It's so simple and archetypal (little wonder, since Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces): a wide-eyed audience stand-in who dreams of seeing something of the world, be a hero and rescue a beautiful princess; a wise old mentor, not long for this world; a charming rogue who learns to value friendship over money; a dastardly villain; and a character who, yes, is at this point still kind of an old-school damsel in distress, but at least has her own mind, some justifiable complaints about her ill-planned rescue, and ideas for how to do a better job. But it takes skill to do this stuff well, and Star Wars does it extremely well.

The script isn't usually given the amount of credit it's due, but it's among the reasons for the success of Star Wars and its immediate ability to capture the imagination. Lucas wrote the thing more than once, never happy with the results, and when Star Wars started filming in Tunisia the screenplay was still unfinished. The process of often sharply critical feedback over several years from Hollywood insiders and Lucas's wife, as well as uncredited dialogue rewrites by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, somehow produced a particular alchemy.

The result is glorious high pulp, instantly quotable and wonderful: "You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy"; "I find your lack of faith disturbing"; "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid"; "Evacuate? In our moment of triumph?"; "The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers", and so on. None of this is remotely how real people talk, but it gives the film an outsized air of adventure and wonder that helps it hit all the high notes.

Then there are the performances. The role of Luke Skywalker at this point is still something of a generic person, but Mark Hamill gets that right: we like and empathise with Luke, and that's what the film needs. The others are allowed to do more, and they're terrific. Alec Guinness forever seems gently amused at being asked to deliver dialogue about Jedi knights and disturbances in the Force, which results in a winning, light performance. Peter Cushing, veteran Hammer Horror vampire hunter, makes for a marvellously icy and authoritative warlord with drive, determination and cruelty to spare.

To me, there are three standouts: Harrison Ford's natural charisma causes him to make the role his own so much that he essentially spun it off into another franchise, as Indiana Jones. Anthony Daniels portrays C-3PO as a self-pitying but fundamentally decent comic foil who gets some of the film's biggest laughs ("Listen to them, they're dying, R2! Curse my metal body, I wasn't fast enough, it's all my fault!") And lastly, David Prowse's physical acting has always been overshadowed by James Earl Jones's voice, but his performance inside the Darth Vader suit is perfect: authoritative and menacing, but very far from emotionless. I adore the scene in which he pauses as he senses Obi-Wan for the first time; it's subtle but all kinds of wonderful.

Star Wars wouldn't be Star Wars without the lovely production design, though: it's chock-full of amazing ideas brilliantly executed. And unlike the second and third prequels, which are full of stuff happening in the background, the first film has the sense to actually briefly focus on the terrific alien suits, grime-covered droids and fossils bleached by the Tatooine suns, giving them each the dignity and two seconds of glory they deserve. (My favourite is and remains the tiny droid skittering away from Chewbacca on the Death Star, beeping in fear.) The film's used-future aesthetic - which belongs exclusively to the good and neutral characters, while the Empire is exquisitely glossy - is wonderfully and consistently realised.

The special effects are extremely good: they look dated, yes, but virtually never unconvincing. The real star is Ben Burtt's sound design, though. From all the mechanical whirring and hissing to Chewbacca's voice and Vader's breathing, the sounds of Star Wars remain instantly recognisable. There's so much high-class craftsmanship here, it really makes you appreciate the often-forgotten art of sound design (and miss it in all the projects that neglect to go beyond mere competence).

So what doesn't hold up? Despite everything, the final film is a bit slight; it zips past having established fairly little of its world beyond rough outlines, and selling some of its character development more through conviction than storytelling logic (Luke's attachment to Obi-Wan, in particular, feels dodgy after so short an acquaintance, especially since he immediately forgets about the people who raised him). The film offers a world of adventure so appealing, it's not surprising people wanted sequels and an enormous expanded universe. But it also feels a little like Star Wars needed those things to round it out, and like, had nothing else ever followed, the film would feel roughly sketched. But if the worst thing I can say about a film is that I want more of its world and characters than it can possibly provide in two hours, well...

Wednesday, 24 June 2015

Every chapter I stole from somewhere else

In Chapter 18 of Dracula, Bram Stoker offers a brief summary of the villain's identity: 'He must, indeed, have been that Voivode Dracula who won his name against the Turk, over the great river on the very frontier of Turkey-land. If it be so, then was he no common man, for in that time, and for centuries after, he was spoken of as the cleverest and the most cunning, as well as the bravest of the sons of the "land beyond the forest".'

The vagueness allows Stoker to gloss over a detail: Vlad III was the Voivode of Wallachia, a mostly lowland principality to the north of the Danube in present-day southern Romania. Transylvania, where Stoker's count has his home, is an entirely different (albeit neighbouring) region, a part of medieval Hungary. Stoker rightly thought the legend of Vlad the Impaler was too good to pass up, so he fudged his history a bit. And we don't mind because he did it in the service of a novel that presents, despite awkward, overheated prose and reactionary politics, a good story.

You know what's pretty much the opposite of a good story, though? Dracula Untold. Seriously.

In the fifteenth century, Vlad Dracula (Luke Evans) rules the principality of Transylvania [sic] as a vassal of the Turkish Empire. When the Turkish envoy Hamza Bey (Ferdinand Kingsley) demands that 1,000 Transylvanian boys - including Vlad's own son (Art Parkinson) - be turned over to the Turks for training as Janissary soldiers, as Vlad himself was, the Prince is distraught. After his attempt to plead personally with Sultan Mehmed II (Dominic Cooper) fails, Vlad refuses to budge, killing the Ottoman party tasked with bringing back the hostages and plunging Transylvania into war.

Realising he lacks the strength to fight off the Turkish army, Vlad visits the monstrous denizen of a mountain cave (Charles Dance), who lends him his vampiric powers. If Vlad manages to resist the craving for human blood for three days, he will return to his normal human self. If he gives in, however, he will become an immortal bloodsucking fiend forever. Realising he has little choice if he is to save his people, Vlad accepts the wager and turns into a superpowered, if increasingly sinister version of himself.

It would be difficult to argue that Dracula was exactly crying out for an origin story. (Not impossible: I for one would love to see a historical fantasy series set in the fifteenth-century Balkans on TV.) But dredging up the making of a hero has been the fashionable way to rekindle audience interest in washed-up properties since Batman Begins in 2005 (Sam Raimi's 2002 Spider-Man was an origin story too, but saw no need to go on about it). Christopher Nolan's Batman films also gifted us the flawed, introspective hero that's spread like measles throughout corporate filmmaking. It's an approach that works fantastically for Batman, but for other characters - like, it turns out, Dracula - it's potentially lethal.

Combine a cookie-cutter origin story, a dark and brooding protagonist and the burden that Dracula Untold is the first film in the Marvel-aping rebooted Universal Monsters cinematic universe, and you have a recipe for disaster. The franchise angle forces the film to end on a bizarre and awful modern-day scene, while its slavish paint-by-numbers approach causes Dracula Untold to run into a serious problem: namely, that Dracula's appeal isn't as a hero, glum or otherwise. What people pay for when going to see a Dracula film is a charismatic immortal villain. Attempting to tell the story of how a virtuous aristocrat became an undead monster isn't impossible. But it would at the very least require the courage to make your protagonist, you know, evil by the end of the film. Instead Evans's Dracula stubbornly remains the same reasonably decent concerned dad, whether he's celebrating Easter with his adoring subjects or slaking his thirst on the blood of thousands of mooks. Worrying about audience sympathies causes writers Matt Sazama and Burk Sharpless to simply give up on character development entirely.

But then, Dracula Untold isn't trying to tell the story of how a monster came to be because, apart from the most cursory of nods, it isn't a horror film. It's a superhero picture, if the shameless and uninspired cribbing from the conventions of the DC and Marvel films of the last decade didn't give that away, and a particularly asinine example of the form: cardboard villains, tedious powers and an adherence to formula so rigid that it chokes whatever life should be there right out of the film. There's even a scene in which silver fills in for kryptonite. In the face of so much formula, who could blame first-time director Gary Shore for falling asleep at the helm?

The film borrows extensively from what has come before. The opening scene, for example - in which voiceover narration explains to us scenes of boys being put through gruelling military training that includes a lot of whipping - is a bafflingly close retelling of the start of 300. Frank Miller's anti-Persian tirade provides the backbone for much of what follows, although Dracula Untold lacks the earlier film's full-throated fascist propagandising. Its Turks are mostly uninspired generic baddies, although the ominous crescents on their tents and repeated references to their menace to the capitals of Christian Europe are quite enough, in the age of Anders Behring Breivik, to qualify as grossly irresponsible. The film is, not to put too fine a point on it, racist trash, its obvious brainlessness aggravating rather than lessening its offensive pandering to fashionable prejudice.

Then there's Vlad's leading of the Transylvanian people to the safety of a monastery in the mountains, borrowed among other antecedents from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. It's indicative of the film's gross lack of any sense of scale: the whole of Transylvania seems to consist of at most a couple of hundred people located in a single castle, and the entire war between Vlad and the Ottoman Empire is over in the required three days (in the real world, meanwhile, a medieval army would take well over a month to cover the distance between Istanbul and Vlad's historical capital of Târgoviște).

Nothing in Dracula Untold, in short, feels like it takes place in a plausible approximation of the real world. It looks fake, too: I left the film convinced its backgrounds were entirely computer-generated only to find out it was shot on location in Northern Ireland - a popular filming location in the age of Game of Thrones though not, alas, one famed for its scenic mountain ranges. The cold metallic colour palette chosen by cinematographer John Schwartzman seems an odd fit, too, for the backwoods medievalism the story would seem to require.

It's tired hackwork, is what it is, and the utterly uninspired performances reflect this. Evans tries, but he has literally nothing to work with; of all the people onscreen, only Charles Dance manages to have some fun with a scenery-chewing, genuinely effective performance. Say what you will about corporate filmmaking, but it guarantees at least a certain professionalism. Dracula Untold, alas, has literally nothing to offer beyond that base amount of competence. It's a product so soulless that it's difficult to be upset no-one involved in it managed to care.

The vagueness allows Stoker to gloss over a detail: Vlad III was the Voivode of Wallachia, a mostly lowland principality to the north of the Danube in present-day southern Romania. Transylvania, where Stoker's count has his home, is an entirely different (albeit neighbouring) region, a part of medieval Hungary. Stoker rightly thought the legend of Vlad the Impaler was too good to pass up, so he fudged his history a bit. And we don't mind because he did it in the service of a novel that presents, despite awkward, overheated prose and reactionary politics, a good story.

You know what's pretty much the opposite of a good story, though? Dracula Untold. Seriously.

In the fifteenth century, Vlad Dracula (Luke Evans) rules the principality of Transylvania [sic] as a vassal of the Turkish Empire. When the Turkish envoy Hamza Bey (Ferdinand Kingsley) demands that 1,000 Transylvanian boys - including Vlad's own son (Art Parkinson) - be turned over to the Turks for training as Janissary soldiers, as Vlad himself was, the Prince is distraught. After his attempt to plead personally with Sultan Mehmed II (Dominic Cooper) fails, Vlad refuses to budge, killing the Ottoman party tasked with bringing back the hostages and plunging Transylvania into war.

Realising he lacks the strength to fight off the Turkish army, Vlad visits the monstrous denizen of a mountain cave (Charles Dance), who lends him his vampiric powers. If Vlad manages to resist the craving for human blood for three days, he will return to his normal human self. If he gives in, however, he will become an immortal bloodsucking fiend forever. Realising he has little choice if he is to save his people, Vlad accepts the wager and turns into a superpowered, if increasingly sinister version of himself.

It would be difficult to argue that Dracula was exactly crying out for an origin story. (Not impossible: I for one would love to see a historical fantasy series set in the fifteenth-century Balkans on TV.) But dredging up the making of a hero has been the fashionable way to rekindle audience interest in washed-up properties since Batman Begins in 2005 (Sam Raimi's 2002 Spider-Man was an origin story too, but saw no need to go on about it). Christopher Nolan's Batman films also gifted us the flawed, introspective hero that's spread like measles throughout corporate filmmaking. It's an approach that works fantastically for Batman, but for other characters - like, it turns out, Dracula - it's potentially lethal.

Combine a cookie-cutter origin story, a dark and brooding protagonist and the burden that Dracula Untold is the first film in the Marvel-aping rebooted Universal Monsters cinematic universe, and you have a recipe for disaster. The franchise angle forces the film to end on a bizarre and awful modern-day scene, while its slavish paint-by-numbers approach causes Dracula Untold to run into a serious problem: namely, that Dracula's appeal isn't as a hero, glum or otherwise. What people pay for when going to see a Dracula film is a charismatic immortal villain. Attempting to tell the story of how a virtuous aristocrat became an undead monster isn't impossible. But it would at the very least require the courage to make your protagonist, you know, evil by the end of the film. Instead Evans's Dracula stubbornly remains the same reasonably decent concerned dad, whether he's celebrating Easter with his adoring subjects or slaking his thirst on the blood of thousands of mooks. Worrying about audience sympathies causes writers Matt Sazama and Burk Sharpless to simply give up on character development entirely.

But then, Dracula Untold isn't trying to tell the story of how a monster came to be because, apart from the most cursory of nods, it isn't a horror film. It's a superhero picture, if the shameless and uninspired cribbing from the conventions of the DC and Marvel films of the last decade didn't give that away, and a particularly asinine example of the form: cardboard villains, tedious powers and an adherence to formula so rigid that it chokes whatever life should be there right out of the film. There's even a scene in which silver fills in for kryptonite. In the face of so much formula, who could blame first-time director Gary Shore for falling asleep at the helm?

The film borrows extensively from what has come before. The opening scene, for example - in which voiceover narration explains to us scenes of boys being put through gruelling military training that includes a lot of whipping - is a bafflingly close retelling of the start of 300. Frank Miller's anti-Persian tirade provides the backbone for much of what follows, although Dracula Untold lacks the earlier film's full-throated fascist propagandising. Its Turks are mostly uninspired generic baddies, although the ominous crescents on their tents and repeated references to their menace to the capitals of Christian Europe are quite enough, in the age of Anders Behring Breivik, to qualify as grossly irresponsible. The film is, not to put too fine a point on it, racist trash, its obvious brainlessness aggravating rather than lessening its offensive pandering to fashionable prejudice.

Then there's Vlad's leading of the Transylvanian people to the safety of a monastery in the mountains, borrowed among other antecedents from The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. It's indicative of the film's gross lack of any sense of scale: the whole of Transylvania seems to consist of at most a couple of hundred people located in a single castle, and the entire war between Vlad and the Ottoman Empire is over in the required three days (in the real world, meanwhile, a medieval army would take well over a month to cover the distance between Istanbul and Vlad's historical capital of Târgoviște).

Nothing in Dracula Untold, in short, feels like it takes place in a plausible approximation of the real world. It looks fake, too: I left the film convinced its backgrounds were entirely computer-generated only to find out it was shot on location in Northern Ireland - a popular filming location in the age of Game of Thrones though not, alas, one famed for its scenic mountain ranges. The cold metallic colour palette chosen by cinematographer John Schwartzman seems an odd fit, too, for the backwoods medievalism the story would seem to require.

It's tired hackwork, is what it is, and the utterly uninspired performances reflect this. Evans tries, but he has literally nothing to work with; of all the people onscreen, only Charles Dance manages to have some fun with a scenery-chewing, genuinely effective performance. Say what you will about corporate filmmaking, but it guarantees at least a certain professionalism. Dracula Untold, alas, has literally nothing to offer beyond that base amount of competence. It's a product so soulless that it's difficult to be upset no-one involved in it managed to care.

Labels:

fantasy,

superheroes,

the middle ages,

Überwald,

vampires

Sunday, 21 December 2014

Battle of the Five Hours

The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies is apparently the shortest of Peter Jackson's Hobbit series, but had you told me it was twice as long as any of the Lord of the Rings films I might well have believed you. The Battle of the Five Armies is, above all, an earnest plea for the importance of structure. It's a film that - after a prologue that feels tacked on from the preceding film - is just an enormous slog, without notable turns, shifts, pauses or high points. It's noisy and epic in its ambitions, while at the same time being utterly inert and tedious.

I should say first, perhaps, that I haven't seen either of the two preceding films. (The release of An Unexpected Journey inspired me to re-read the book, at least.) But if watching the first two installments is necessary to enjoy Battle of the Five Armies, that hardly improves things: Each film in a trilogy, you'd hope, should have a satisfying arc of its own and be enjoyable watched in isolation, especially since they're being released a year apart. This is something, incidentally, that Jackson's own Lord of the Rings trilogy achieves in adapting a single novel that was split into three volumes at the insistence of Tolkien's publisher, even if the writers have to strain mightily to make it happen (especially in The Two Towers, where as a consequence the seams are most obvious). For The Hobbit, Jackson didn't even try.

The plot, what there is of it: The company of dwarves having finally reached the Lonely Mountain, their 'burglar', hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Martin Freeman), steals the Arkenstone from Smaug the dragon (Benedict Cumberbatch). Angered, Smaug flies off to Lake-town and burns it to the ground, but is slain by Bard the Bowman (Luke Evans) in the process. Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage), suddenly freed from the headache of how to get rid of Smaug, refounds the dwarven kingdom of Erebor and, increasingly overcome by the allure of gold, has his followers fortify the entrance before others stake a claim. As indeed they do: Bard arrives with the people of Lake-town to demand the share of the treasure Thorin promised, to help rebuild the town; he is soon joined by the army of King Thranduil of the wood-elves (Lee Pace), who is incensed at Thorin deceiving and escaping him. Thorin's pig-headed refusal to negotiate is backed up when his cousin Dáin Ironfoot (Billy Connolly) arrives with an army of dwarves. Before the sides come to blows, however, a horde of orcs led by Azog the Defiler (Manu Bennett) shows up and much mayhem ensues.

There's also a subplot involving Gandalf and some characters you may remember from the Rings films fighting the necromancer in Dol Guldur, but that takes up all of five minutes.

The Battle of the Five Armies is pretty to look at, no doubt: the wintry surrounds of the Lonely Mountain are a triumph of landscape photography, set design and cinematography. Set in cold northern wastes the Rings films never touched on, The Battle of the Five Armies serves up new, interesting environs. And there are some genuine thrills there, too: Dáin's dwarven phalanx in action is a sight to see, even if the Warhammer-esque blockiness of the dwarf design, which I've never been a fan of, still spoils the view somewhat.

On the downside there are the terrible CGI-enhanced baddies. The Rings films, for all the criticism rightly levelled at them, were heaven for fans of practical effects. The design of the orcs, using masks, prosthetics and make-up, gave the creatures a gross physicality that lined up with the spittle, body odour and vile dietary habits that defined them as fictional versions of the working-class people of Tolkien's patrician nightmares. CGI allows the creation of wonders that old-school effects have never been able to achieve, but the trade-off is still often a lack of heft and weight.

There is no reality and thus no threat to these orcs, snarl as they might. Compare the magnificant fight between Aragorn and Lurtz in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) to Thorin's endless, mind-numbingly boring battle against Azog in this one, and despair. (A similar scene, in which Legolas leaps along a collapsing walkway like Super Mario, caused peals of laughter to ring around the auditorium.) With the Hobbit films (let's just boldly assume this problem affects the previous two films as well), Jackson has gone full-on Phantom Menace.

The film is hopelessly dragged down is its sheer length, forced by the mercenary decision to turn The Hobbit not into one, nor two, but three feature-length films. Reverse that decision, and this entire film could be wrapped up in the 45 minutes the material merits; the enormous structural problem would disappear; the fact that the nominal protagonist has nothing to do would be much less noticeable. Lengthy, pointless scenes involving cowardly Alfrid (Ryan Gage), in which jokes about such humorous subjects as men wearing women's clothes are expected to provide comic relief, could be cut, as could a bizarre psychedelic sequence involving Thorin among Smaug's gold that shows us Jackson using the freedom granted by a near-total absence of plot to baffling effect.

But the film's length isn't its only problem: indeed some fairly important aspects of the book are passed over in downright indecent haste (the arrival of Beorn and the eagles), while threads are left dangling in other places (we're left to assume, for example, that Dáin and the elves defeated the orc army after its leaders are killed elsewhere, but the film doesn't see the need to spell out the outcome of the titular battle). There's the film's uninspiring visual language too: where Rings had stunning images, even if they were often an homage to greater works, The Battle of the Five Armies offers little to look at, as if Jackson was overcompensating for his tendency to gawk at his sets.

Anyway, I'm glad this new trilogy is over, and sort of pleased Jackson doesn't have the rights to any more of Tolkien's works.

I should say first, perhaps, that I haven't seen either of the two preceding films. (The release of An Unexpected Journey inspired me to re-read the book, at least.) But if watching the first two installments is necessary to enjoy Battle of the Five Armies, that hardly improves things: Each film in a trilogy, you'd hope, should have a satisfying arc of its own and be enjoyable watched in isolation, especially since they're being released a year apart. This is something, incidentally, that Jackson's own Lord of the Rings trilogy achieves in adapting a single novel that was split into three volumes at the insistence of Tolkien's publisher, even if the writers have to strain mightily to make it happen (especially in The Two Towers, where as a consequence the seams are most obvious). For The Hobbit, Jackson didn't even try.

The plot, what there is of it: The company of dwarves having finally reached the Lonely Mountain, their 'burglar', hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Martin Freeman), steals the Arkenstone from Smaug the dragon (Benedict Cumberbatch). Angered, Smaug flies off to Lake-town and burns it to the ground, but is slain by Bard the Bowman (Luke Evans) in the process. Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage), suddenly freed from the headache of how to get rid of Smaug, refounds the dwarven kingdom of Erebor and, increasingly overcome by the allure of gold, has his followers fortify the entrance before others stake a claim. As indeed they do: Bard arrives with the people of Lake-town to demand the share of the treasure Thorin promised, to help rebuild the town; he is soon joined by the army of King Thranduil of the wood-elves (Lee Pace), who is incensed at Thorin deceiving and escaping him. Thorin's pig-headed refusal to negotiate is backed up when his cousin Dáin Ironfoot (Billy Connolly) arrives with an army of dwarves. Before the sides come to blows, however, a horde of orcs led by Azog the Defiler (Manu Bennett) shows up and much mayhem ensues.

There's also a subplot involving Gandalf and some characters you may remember from the Rings films fighting the necromancer in Dol Guldur, but that takes up all of five minutes.

The Battle of the Five Armies is pretty to look at, no doubt: the wintry surrounds of the Lonely Mountain are a triumph of landscape photography, set design and cinematography. Set in cold northern wastes the Rings films never touched on, The Battle of the Five Armies serves up new, interesting environs. And there are some genuine thrills there, too: Dáin's dwarven phalanx in action is a sight to see, even if the Warhammer-esque blockiness of the dwarf design, which I've never been a fan of, still spoils the view somewhat.

On the downside there are the terrible CGI-enhanced baddies. The Rings films, for all the criticism rightly levelled at them, were heaven for fans of practical effects. The design of the orcs, using masks, prosthetics and make-up, gave the creatures a gross physicality that lined up with the spittle, body odour and vile dietary habits that defined them as fictional versions of the working-class people of Tolkien's patrician nightmares. CGI allows the creation of wonders that old-school effects have never been able to achieve, but the trade-off is still often a lack of heft and weight.

There is no reality and thus no threat to these orcs, snarl as they might. Compare the magnificant fight between Aragorn and Lurtz in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) to Thorin's endless, mind-numbingly boring battle against Azog in this one, and despair. (A similar scene, in which Legolas leaps along a collapsing walkway like Super Mario, caused peals of laughter to ring around the auditorium.) With the Hobbit films (let's just boldly assume this problem affects the previous two films as well), Jackson has gone full-on Phantom Menace.

The film is hopelessly dragged down is its sheer length, forced by the mercenary decision to turn The Hobbit not into one, nor two, but three feature-length films. Reverse that decision, and this entire film could be wrapped up in the 45 minutes the material merits; the enormous structural problem would disappear; the fact that the nominal protagonist has nothing to do would be much less noticeable. Lengthy, pointless scenes involving cowardly Alfrid (Ryan Gage), in which jokes about such humorous subjects as men wearing women's clothes are expected to provide comic relief, could be cut, as could a bizarre psychedelic sequence involving Thorin among Smaug's gold that shows us Jackson using the freedom granted by a near-total absence of plot to baffling effect.

But the film's length isn't its only problem: indeed some fairly important aspects of the book are passed over in downright indecent haste (the arrival of Beorn and the eagles), while threads are left dangling in other places (we're left to assume, for example, that Dáin and the elves defeated the orc army after its leaders are killed elsewhere, but the film doesn't see the need to spell out the outcome of the titular battle). There's the film's uninspiring visual language too: where Rings had stunning images, even if they were often an homage to greater works, The Battle of the Five Armies offers little to look at, as if Jackson was overcompensating for his tendency to gawk at his sets.

Anyway, I'm glad this new trilogy is over, and sort of pleased Jackson doesn't have the rights to any more of Tolkien's works.

Monday, 11 June 2012

Grimm up north

I'm a Hun. By which I mean: whereas most people in the Anglo-Saxon world first encountered Grimm's fairy-tales through the classic Disney adaptations, Kinder- und Hausmärchen was read to me when I was a wee lad. Astonishingly to those of us who spend a lot of time fretting over what innocent young people's minds might be exposed to, these fairy-tales regularly feature mutilation, blood magic, extravagant gore, infanticide, parricide, matricide - more or less every -cide you could think of, in fact.

I'm thus not terribly impressed with Snow White and the Huntsman's central gimmick, its claim to be a darker and edgier version of the Snow White tale. True, like the revolution the film is hardly a tea party: but considering that unlike the fairy-tale it features neither cannibalism nor anybody being publicly tortured to death it is in fact less vicious than the Brothers Grimm version. That's a flaw only inasmuch as a film advertised as dark and brutal ought not to pull its punches. But an adaptation faithful to the Grimm spirit would be a great many things, conventionally entertaining not among them.

Magnus (Noah Huntley) is a wise and benevolent king until he is killed by his second wife, the beautiful witch Ravenna (Charlize Theron). Snow White, Magnus's daughter from his first marriage, is imprisoned while Ravenna, aided by her brother, Finn (Sam Spruell), rules the kingdom with an iron fist. (Side note: in the first edition of Grimm's fairy-tales, the evil queen is Snow White's biological mother, while later versions turn her into her stepmother.) Years later, the grown Snow White (Kristen Stewart) manages to escape and flees into the Dark Forest, where sensible people fear to tread. Ravenna, anxious to use Snow White's heart to remain young forever, gives the job of hunting the girl down to the drunken, bitter Huntsman (Chris Hemsworth), promising to bring his wife back to life.

The Huntsman doesn't take long to lead Finn and his men to Snow White, but when he realises that Ravenna's promise was a lie he turns on his employers and decides to protect the princess instead. After a number of adventures that serve little purpose except to pad the running time, the two run into a band of dwarfs, former miners turned brigands (Ian McShane, Bob Hoskins, Ray Winstone, Nick Frost, Eddie Marsan, Toby Jones, Johnny Harris and Brian Gleeson), as well as Snow White's childhood friend William (Sam Claflin), the son of Duke Hammond (Vincent Regan), the last holdout against Ravenna's reign. After surviving a poisoned apple, Snow White decides to take the reins and lead an army against Ravenna's castle.

Snow White and the Huntsman may be horrendously broken in ways we'll get to, but it has absolutely gorgeous costume design courtesy of the great Colleen Atwood (of Sweeney Todd and Sleepy Hollow). And though some of the production design is questionable (did Snow White really need the White Tree of Gondor on her shield?), all in all Dominic Watkins, David Warren and their team do a terrific job of creating a consistently moody fantasy world with some unique touches. (Whoever came up with the moss-covered reptiles needs to be hired for every single production right now.) It's a shame that Greig Fraser's rote cinematography can't keep up with those chaps, or that first-time director Rupert Sanders otherwise provides little evidence of the lavish $170 million budget he got to play with.

Well then: that script. All in all, the story is perfectly acceptable, a fine attempt to turn the fairy-tale into a medieval fantasy narrative. But the final screenplay credited to Evan Daugherty, John Lee Hancock and Hossein Amini is painfully overstuffed. There is a scene involving a village only inhabited by women, a battle against a bridge troll and an encounter with a forest spirit nicked from Mononoke-hime, all of them just padding; more seriously, whole characters (most obviously Claflin's William) could be cut without harming the story in the least. All that dead weight stretching the film to 127 minutes isn't just irritating, it also ruins the pacing. Snow White and the Huntsman just stumbles from one thing that happens to another, without ever developing more than a simulacrum of the expected emotional arc. Oh, the required scenes - stirring speeches! tender kisses! ferocious swordfights! - are there, they just don't have the intended impact in a film so drunkenly off-kilter.

Against those odds actors can only do so much. Stewart and Hemsworth do what they do best; Theron's performance, terrific at first, gradually becomes less effective as the film wears on. The real problem is tone. If you want to be a dark, grown-up fantasy film, you really can't delve into 'little people are funny!' humour every once in a while, a lesson the Lord of the Rings films taught us a decade ago; and if it so happens that your all-star cast of dwarfs is far and away the best part of the film (seriously, I'd watch a spin-off about little Ian McShane & Friends any day), you might consider altering the whole project accordingly. As it is, Snow White and the Huntsman lands uncomfortably in cinematic no man's land.

I'm thus not terribly impressed with Snow White and the Huntsman's central gimmick, its claim to be a darker and edgier version of the Snow White tale. True, like the revolution the film is hardly a tea party: but considering that unlike the fairy-tale it features neither cannibalism nor anybody being publicly tortured to death it is in fact less vicious than the Brothers Grimm version. That's a flaw only inasmuch as a film advertised as dark and brutal ought not to pull its punches. But an adaptation faithful to the Grimm spirit would be a great many things, conventionally entertaining not among them.

Magnus (Noah Huntley) is a wise and benevolent king until he is killed by his second wife, the beautiful witch Ravenna (Charlize Theron). Snow White, Magnus's daughter from his first marriage, is imprisoned while Ravenna, aided by her brother, Finn (Sam Spruell), rules the kingdom with an iron fist. (Side note: in the first edition of Grimm's fairy-tales, the evil queen is Snow White's biological mother, while later versions turn her into her stepmother.) Years later, the grown Snow White (Kristen Stewart) manages to escape and flees into the Dark Forest, where sensible people fear to tread. Ravenna, anxious to use Snow White's heart to remain young forever, gives the job of hunting the girl down to the drunken, bitter Huntsman (Chris Hemsworth), promising to bring his wife back to life.

The Huntsman doesn't take long to lead Finn and his men to Snow White, but when he realises that Ravenna's promise was a lie he turns on his employers and decides to protect the princess instead. After a number of adventures that serve little purpose except to pad the running time, the two run into a band of dwarfs, former miners turned brigands (Ian McShane, Bob Hoskins, Ray Winstone, Nick Frost, Eddie Marsan, Toby Jones, Johnny Harris and Brian Gleeson), as well as Snow White's childhood friend William (Sam Claflin), the son of Duke Hammond (Vincent Regan), the last holdout against Ravenna's reign. After surviving a poisoned apple, Snow White decides to take the reins and lead an army against Ravenna's castle.

Snow White and the Huntsman may be horrendously broken in ways we'll get to, but it has absolutely gorgeous costume design courtesy of the great Colleen Atwood (of Sweeney Todd and Sleepy Hollow). And though some of the production design is questionable (did Snow White really need the White Tree of Gondor on her shield?), all in all Dominic Watkins, David Warren and their team do a terrific job of creating a consistently moody fantasy world with some unique touches. (Whoever came up with the moss-covered reptiles needs to be hired for every single production right now.) It's a shame that Greig Fraser's rote cinematography can't keep up with those chaps, or that first-time director Rupert Sanders otherwise provides little evidence of the lavish $170 million budget he got to play with.

Well then: that script. All in all, the story is perfectly acceptable, a fine attempt to turn the fairy-tale into a medieval fantasy narrative. But the final screenplay credited to Evan Daugherty, John Lee Hancock and Hossein Amini is painfully overstuffed. There is a scene involving a village only inhabited by women, a battle against a bridge troll and an encounter with a forest spirit nicked from Mononoke-hime, all of them just padding; more seriously, whole characters (most obviously Claflin's William) could be cut without harming the story in the least. All that dead weight stretching the film to 127 minutes isn't just irritating, it also ruins the pacing. Snow White and the Huntsman just stumbles from one thing that happens to another, without ever developing more than a simulacrum of the expected emotional arc. Oh, the required scenes - stirring speeches! tender kisses! ferocious swordfights! - are there, they just don't have the intended impact in a film so drunkenly off-kilter.

Against those odds actors can only do so much. Stewart and Hemsworth do what they do best; Theron's performance, terrific at first, gradually becomes less effective as the film wears on. The real problem is tone. If you want to be a dark, grown-up fantasy film, you really can't delve into 'little people are funny!' humour every once in a while, a lesson the Lord of the Rings films taught us a decade ago; and if it so happens that your all-star cast of dwarfs is far and away the best part of the film (seriously, I'd watch a spin-off about little Ian McShane & Friends any day), you might consider altering the whole project accordingly. As it is, Snow White and the Huntsman lands uncomfortably in cinematic no man's land.

Tuesday, 13 March 2012

Theseus war

Like it or not, 300 changed everything.* After hubris and audience fatigue had caused the ancient epic of the early 2000s to collapse, Zack Snyder's 2007 debut transformed the sword-and-sandal film into its present form. The subgenre of hyper-masculine, deliberately artificial-looking mid-budget pictures is still not dead, despite the fact that it has yet to produce an actual good film apart from its progenitor.

Immortals, alas, isn't the yearned-for exception to the rule. Whatever the intentions of the people behind it, the finished product is a rip-off of 300 by way of Clash of the Titans. Whatever other merits 300, a film I liked, might claim, it was hardly the womb of ideas; and if you're copying a remake, well... Suffice it to say that Immortals follows previous sword-and-sandal films so slavishly that it ends up with no identity of its own to speak of.

Anyway, the film is the story of Theseus (Henry Cavill), though considering the indifference with which the script treats Greek mythology I don't know why they bothered. Theseus is raised in a nameless village by his mother (Anne Day-Jones) and High Chancellor Sutler (John Hurt). When the evil king Hyperion (Mickey Rourke) sends out his armies in search of the fabled Epirus Bow, Theseus is enslaved, but he soon escapes with a ragtag bunch of misfits including the thief Stavros (Stephen Dorff) and the virgin oracle Phaedra (Freida Pinto).

Meanwhile the Olympians, led by Zeus (Luke Evans, who played Apollo in Clash of the Titans), fear that Hyperion may use the Epirus Bow to release the imprisoned Titans, but will not interfere with the affairs of mankind. Theseus finds the bow in a rock, and they take the weapon to Mount (!) Tartarus, where a Hellenic army has gathered to protect the Titans' prison from Hyperion's fanatical hordes. Along the way, they of course manage to lose the bow to Hyperion, setting the scene for an ugly showdown.

The script is quite simply boring as hell, and no-one could blame the actors for failing to breathe any life into it. Considering they use a literal deus ex machina more than once when the heroes find themselves in a pickle, writers Charley and and Vlas Parlapanides were presumably not taking their job too seriously. The story is padded to twice the necessary length, while still being something of a skeleton to hang an actual plot on: there isn't the slightest suggestion of geography or ethnography, real or fictional. One presumes the film is set in some fictionalised version of a country the script refers to as 'Hellenes', presumably because 'Greece' is too vulgar and 'Hellas' is too correct. The one good idea - the fight against the Minotaur, who is a large, brutish human wearing a wire bull's mask here - seems shoehorned in and is lost in a sea of awfulness.

The visuals don't help at all. Sure, the film's notion of Olympus - here, a darkish set populated by gods wearing silly hats - is better than the tinfoil-and-eyeliner extravaganza Clash of the Titans tried to sell us. Director Tarsem Singh conjures up some striking images, but it's all thoroughly ruined by the colour scheme, the very same mix of dark brown and gold with occasional dashes of colour that 300 should by all rights have killed off. That a very narrow aesthetic should dominate a subgenre would be merely irritating; but it really undoes Immortals, for what better way to declare yourself a 300 clone than to ape every detail of that film's look? Let's hope the upcoming Wrath of the Titans at last puts a stake through the heart of the sword-and-sandal film so that one day there'll be worthwhile films about the ancient world.

*Pathfinder, released a month after 300, may be safely ignored, since unlike the Spartan massacre it sank like a stone at the box office.

Immortals, alas, isn't the yearned-for exception to the rule. Whatever the intentions of the people behind it, the finished product is a rip-off of 300 by way of Clash of the Titans. Whatever other merits 300, a film I liked, might claim, it was hardly the womb of ideas; and if you're copying a remake, well... Suffice it to say that Immortals follows previous sword-and-sandal films so slavishly that it ends up with no identity of its own to speak of.

Anyway, the film is the story of Theseus (Henry Cavill), though considering the indifference with which the script treats Greek mythology I don't know why they bothered. Theseus is raised in a nameless village by his mother (Anne Day-Jones) and High Chancellor Sutler (John Hurt). When the evil king Hyperion (Mickey Rourke) sends out his armies in search of the fabled Epirus Bow, Theseus is enslaved, but he soon escapes with a ragtag bunch of misfits including the thief Stavros (Stephen Dorff) and the virgin oracle Phaedra (Freida Pinto).

Meanwhile the Olympians, led by Zeus (Luke Evans, who played Apollo in Clash of the Titans), fear that Hyperion may use the Epirus Bow to release the imprisoned Titans, but will not interfere with the affairs of mankind. Theseus finds the bow in a rock, and they take the weapon to Mount (!) Tartarus, where a Hellenic army has gathered to protect the Titans' prison from Hyperion's fanatical hordes. Along the way, they of course manage to lose the bow to Hyperion, setting the scene for an ugly showdown.

The script is quite simply boring as hell, and no-one could blame the actors for failing to breathe any life into it. Considering they use a literal deus ex machina more than once when the heroes find themselves in a pickle, writers Charley and and Vlas Parlapanides were presumably not taking their job too seriously. The story is padded to twice the necessary length, while still being something of a skeleton to hang an actual plot on: there isn't the slightest suggestion of geography or ethnography, real or fictional. One presumes the film is set in some fictionalised version of a country the script refers to as 'Hellenes', presumably because 'Greece' is too vulgar and 'Hellas' is too correct. The one good idea - the fight against the Minotaur, who is a large, brutish human wearing a wire bull's mask here - seems shoehorned in and is lost in a sea of awfulness.

The visuals don't help at all. Sure, the film's notion of Olympus - here, a darkish set populated by gods wearing silly hats - is better than the tinfoil-and-eyeliner extravaganza Clash of the Titans tried to sell us. Director Tarsem Singh conjures up some striking images, but it's all thoroughly ruined by the colour scheme, the very same mix of dark brown and gold with occasional dashes of colour that 300 should by all rights have killed off. That a very narrow aesthetic should dominate a subgenre would be merely irritating; but it really undoes Immortals, for what better way to declare yourself a 300 clone than to ape every detail of that film's look? Let's hope the upcoming Wrath of the Titans at last puts a stake through the heart of the sword-and-sandal film so that one day there'll be worthwhile films about the ancient world.

*Pathfinder, released a month after 300, may be safely ignored, since unlike the Spartan massacre it sank like a stone at the box office.

Monday, 20 February 2012

Hyborian twilight

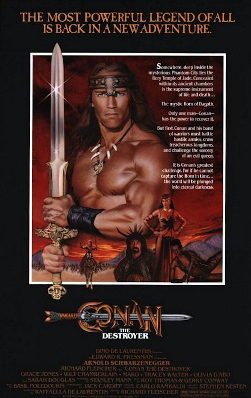

Like its predecessor, Conan the Destroyer didn't set cinema on fire. But in an industry of marginal profits, the film's considerable success at the box office made a third film set in the world of Robert E. Howard all but inevitable. That film, Conan the Conqueror - the long-promised story that shall also be told, of how Conan became a king in his own hand -, never left development hell; and for that we can thank the ignominious failure of the series spin-off Red Sonja.

Like its predecessor, Conan the Destroyer didn't set cinema on fire. But in an industry of marginal profits, the film's considerable success at the box office made a third film set in the world of Robert E. Howard all but inevitable. That film, Conan the Conqueror - the long-promised story that shall also be told, of how Conan became a king in his own hand -, never left development hell; and for that we can thank the ignominious failure of the series spin-off Red Sonja.Red Sonja's production was rushed compared to the two-year gap between the Conan films. I've remarked on the breakneck pace the Italian film industry was capable of in its glory days, and if Richard Fleischer did not quite match Mario Bava's feat of releasing two of his films twelve days apart, it's still worth noting that Conan the Destroyer left cinemas in August 1984 and principal photography for Red Sonja took place that same November, for a summer 1985 release. That sort of pace may be common in low-budget horror, but it's quite something for sword and sorcery, which calls for massive sets, landscape photography and epic battles.

Those three months during the autumn of 1984, however, saw the release of The Terminator. That film's massive success - a worldwide gross of $78 million, comparable to the Conan films but nothing to sniff at considering it had only a third of the sword-and-sorcery films' budget - suggested to Schwarzenegger that he had a legitimate, loincloth-free career ahead of him. When Red Sonja bombed, taking in less than $7m on a $17.9m budget, he abandoned the barbarian genre and became the action/comedy star - and eventually the politician and philanderer - we know and possibly still love today.

When Red Sonja (Brigitte Nielsen) rejects the lesbian advances of the evil queen Gedren (Sandahl Bergman), Gedren has her family murdered while Sonja is raped by her soldiers and left for dead before being revived by a spirit voice. (It's never revealed who this spirit - who speaks to Sonja only twice in the course of the film, never in a plot-relevant function - is, which strikes me as one of the tell-tale signs of a script that was butchered and stitched together again by some literary Leatherface.)

Later, somewhere else, a group of priestesses tries to destroy a dangerous talisman, but they're attacked and killed by the goons of Gedren, who wants the power of the talisman for herself to rule the world. Sonja's sister Varna (Janet Agren) manages to flee, but is shot in the back before being rescued by random hero-lord 'Kalidor' (Arnold Schwarzenegger). It remains one of the film's mysteries why it was felt necessary to create a character who is clearly Conan with the serial numbers filed off: legal reasons, perhaps. Anyway, Kalidor messily kills several of Gedren's goons (Red Sonja cranks up the gore to Conan the Barbarian levels again, after the tamer Destroyer) and carries the dying Varna off to Sonja, who has been trained as a mighty warrior by a vaguely Oriental sword-master (Tad Horino).

When Sonja finds out what's going on, she decides to stop Gedren, initally leaving Kalidor who nonetheless, as Tim Brayton puts it, 'just pops in like a wacky neighbor on a sitcom' during the film's first half. She fights and kills the warlord Brytag (Pat Roach) for no discernible reason and encounters Tarn (Ernie Reyes Jr.) and Falkon (Paul Smith), a child prince and his manservant who have lost their kingdom to Gedren's newly powerful forces. Eventually, the four make it through the wilderness, encountering exactly no people, and square off against Gedren and her magic tricks.

Though undeniably very bad - if Schwarzenegger's jest about punishing his progeny by subjecting them to this film were true, it would constitute child abuse - Red Sonja is at least as 'good' as Conan the Destroyer, and feels a lot better by mercifully coming in under ninety minutes. Written by two Britons, Clive Exter (who later wrote no fewer than twenty-three episodes of Jeeves and Wooster, if you can believe it) and George MacDonald Fraser (who co-wrote Octopussy), Red Sonja's plot is as unsteady and aimless as that of the preceding films, but it's a whole lot less padded, avoiding the cosmic tedium of Destroyer's sleepy second half. The worst thing you can say about is that it introduces that shopworn trope, the Annoying Kid; but at least Tarn turns heroic fairly early on.

At the same time, the casting departments must have been mad as a hatter convention, for the sheer number of series veterans re-cast in totally different roles makes viewing a profoundly baffling experience. Besides Schwarzenegger - who, as the film's most bankable star, is billed above the then unknown Nielsen - there's Bergman, who played Conan's true, sadly nameless love in Barbarian, rendered less recognisable by a mask covering half her face, a fairly terrible black wig, and a deliciously hammy performance. The casting of Pat Roach, who played the illusionist Toth-Amon in Destroyer, as the villainous Brytag is less justifiable, especially since his cameo is mere padding. Danish bodybuilder Sven-Ole Thorsen, however, takes the cake, with his third character in as many films.

Schwarzenegger's performance is, well, vintage Arnie: no-one could make a line like 'She's dead. [Pause.] And the living have work to do' sound quite so earnest yet hilarious. But let's consider Brigitte Nielsen for a moment. Twenty-one years old, with no real acting experience, her uninflected, wooden performance is truly horrendous in exactly that oddly fitting Schwarzeneggerian mould, and they're perfectly matched on set. But where the Austrian reached superstardom, Nielsen briefly became Mrs Sylvester Stallone, met Ronald Reagan, appeared in Playboy a couple of times and has lived out the rest of her career on reality television. Just a few weeks ago, Nielsen won the German version of I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here!.

Richard Fleischer, returning to the director's chair after Conan the Destroyer, largely keeps it steady. At some point, though, he must have decided to prove that a leopard can change its spots and also why it shouldn't, by serving up a couple of absolutely nonsensical first-person shots during sword-fighting scenes. It's in the special effects department that Red Sonja is a real let-down, however. Whether it was time or money, the film resorts to mattes - gorgeously painted mattes, I grant - where John Milius in his Barbarian days would probably have built a full set. Contrast the visuals of Conan the Barbarian with the pretty but totally artificial look of Red Sonja: