Properly done, historical fiction ought to be fascinating. It tells us, after all, how we came to be, and evokes a time and place very different from our own yet startlingly familiar. Unfortunately, though, it's usually

not properly done. As someone who's passionate about history, here are some personal bugbears:

(1) Ideological anachronism. This is probably the single most widespread phenomenon in historical fiction. The hero will inevitably be the one character whose views are most similar to the dominant assumptions of early twenty-first century society, while everyone else is dismissed. For examples see

Kingdom of Heaven and, in Germany, anything written by

Rebecca Gablé.

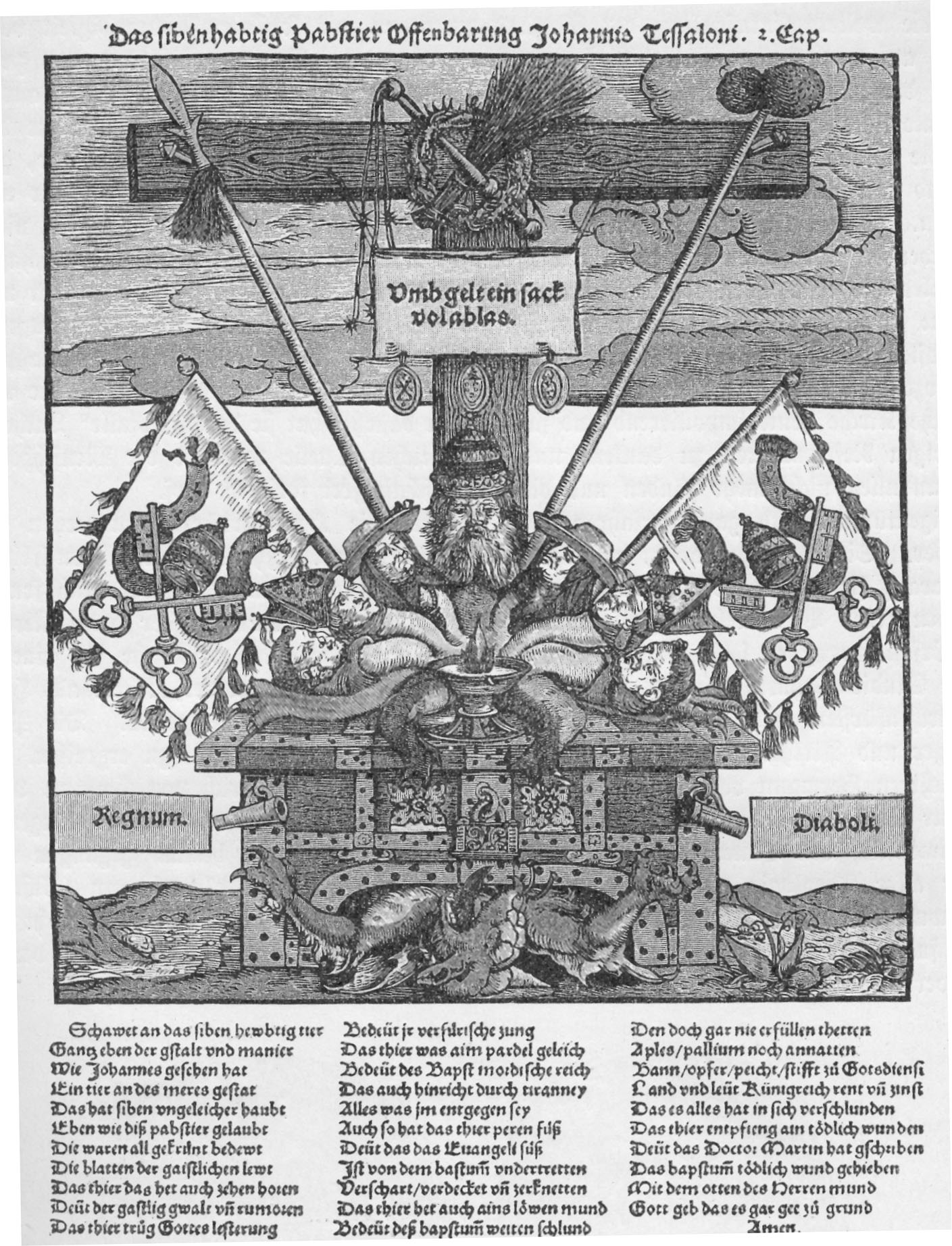

(2) Soapboxing mixed with wish fulfilment. Hate Christianity with the fury of a thousand suns? Write a novel in which - reality be damned - all Christians are prudish, venal, effeminate caricatures to be derided and killed by your manly pagan heroes and make millions like

Bernard Cornwell! Also applicable if you dislike feminism, pacifism and democracy, because in ye olden days men were still real men, just like your own warrior soul would be if it wasn't trapped by the political correctness brigade shoving rights for women and black people down everyone's throats.

(3) The influence of the bodice-ripper. Reducing complex historical processes to sex is tempting: it's much easier to write than all that politics and religion, and it'll sell like hot cakes. But bodice-rippers are notorious for their misogynistic bent. Their women long to be mastered by a manly man - sometimes to the point of rape apologia. At the same time, bodice-rippers refuse to take real women seriously and concede they might have something worthwhile to offer beside bedroom stories. For every Margaret Elphinstone writing terrific female-centred novels like

The Sea Road, there are ten

Philippa Gregory paperbacks.

It's before this background that Hilary Mantel's

Wolf Hall matters. It's not that it's high-brow as opposed to the low-brow fare outlined above: it's that

this is what popular fiction should look like, and to hell with the fraudsters who'd have you accept less. Winning both the Booker Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award,

Wolf Hall was the most critically acclaimed historical novel in quite a long time. But it left historical fiction aficionados confused - witness the book's three-and-a-half stars rating on Amazon - by the almost total absence of the blood, guts, and graphic sex one has come to expect from the Tudors in works ranging from Gregory's novels to, er,

The Tudors.

Instead we get an honest-to-God fascinating central character: Thomas Cromwell, first seen as a teenager in 1500 being beaten within an inch of his life by his choleric father Walter, a Putney blacksmith. Thomas flees to Europe to become a mercenary, and by 1527 he's established himself as a London lawyer and right-hand man to Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII's Lord Chancellor. When Wolsey falls from power over his failure to procure a papal annulment of Henry's marriage to Katherine of Aragon, Cromwell stays behind to look after his patron's cause in his ill-fortune.

After Wolsey's death, Cromwell rises to influence at Henry's court by advancing the case of Anne Boleyn, who longs to finally displace the obstreperous Katherine and become queen. This is only accomplished by flagrantly disregarding the pope, and after Henry's marriage to Anne Cromwell pushes forward the creation of an English national church with Henry at its head. In his private life, meanwhile, he mourns the loss of his wife and daughters to disease while acquiring an extended household of protégés and becoming a surrogate father to the wards he takes in.

Mantel writes all this in the present tense and third person, while never leaving Cromwell's perspective. He's a self-taught multilingual scholar, but his rise to power is due mostly to a pragmatic ruthlessness: if Henry's cause is best advanced by schism, Cromwell will choose that course. He can never quite leave his low birth behind and is haunted by the ghosts of his father and his own family, but he's unafraid to push aside aristocrats and churchmen alike to make Henry supreme ruler of his country.

The prose is beautiful: as precise as Cromwell's mind, it's sophisticated but never excessively flowery. What pleased me most is the effusion of detail, all the little touches of Tudor England: the liturgical year (All Hallows Eve is 'the time when the tally-keepers of Purgatory, its clerks and gaolers, listen in to the living, who are praying for the dead', p. 154), Christmas decorations ('wreaths of holly and ivy, of laurel and ribboned yew', p. 169), the harrowing and subtle description of the aftermath of a Lollard's death at the stake ('When the crowd drifted home, chattering, you could tell the ones who'd been on the wrong side of the fire, because their faces were grey with wood-ash', p. 355).

Mantel takes the period seriously, refusing to reduce it to the Tudor Theme Park popular entertainment presents. Her characters' lives are extraordinarily full and complete, while she is also a master of economy in sketching them.

Wolf Hall is a masterclass in the importance of character, its large cast never seeming less than real human beings, from the coarse, relic-obsessed Duke of Norfolk to the generous, violent, charming, approval-craving Henry, and right down to the common people.

That's true of the world of ideas, too. Instead of simply ignoring the issue of the Reformation, as much popular Tudor fiction does,

Wolf Hall spends long pages dealing with Tyndale's writings smuggled across the Channel, with Thomas More, Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer discussing Purgatory and the role of the Church (the fact that the dispute between Reformers and Catholics was at bottom an ecclesiological one is brought out quite clearly). Cromwell himself appears clear-eyed and thoughtful, contemptuous of superstitions while attempting to retain a Catholic orthodoxy and a church hierarchy loyal to the sovereign.

In contrast to the pessimistic Thomas More, Cromwell is consciously creating a new England, one in which the monarchy will stand above all, sweeping aside the manifold entrenched privileges and powers of the middle ages: no pope, bishop or duke is to stand in the way of the king's importance and untrammelled power. The

final vision of this new kingship is well articulated in

Hamlet 3.3-7-23:

GUILDENSTERN We will ourselves provide.

Most holy and religious fear it is

To keep those many many bodies safe

That live and feed upon your majesty.

ROSENCRANTZ The single and peculiar life is bound

With all the strength and armour of the mind

To keep itself from noyance; but much more

That spirit upon whose weal depends and rests

The lives of many. The cess of majesty

Dies not alone but like a gulf doth draw

What's near it with it; or it is a massy wheel,

Fixed on the summit of the highest mount

To whose huge spokes ten thousand lesser things

Are mortised and adjoined, which when it falls

Each small annexment, petty consequence,

Attends the boisterous ruin. Never alone

Did the king sigh but with a general groan.

(Edition: Thompson and Taylor, London: Arden, 2006, based upon the 1604-5 Second Quarto Text)

This royal supremacy, however, is not asserted easily or totally. When he sends out ambassadors to compel all subjects to swear allegiance to Henry's new position as Head of the Church, Cromwell knows that he won't be able to vanquish the old powers completely:

[B]eneath Cornwall, beyond and beneath this whole realm of England, beneath the sodden marches of Wales and the rough territory of the Scots border, there is another landscape; there is a buried empire, which he fears his commissioners cannot reach. Who will swear the hobs and boggarts who live in the hedges and in hollow trees, and the wild men who hide in the woods? Who will swear the saints in their niches, and the spirits that cluster at holy wells rustling like fallen leaves, and the miscarried infants dug into unconsecrated ground: all those unseen dead who hover in winter around forges and village hearths, trying to warm their bare bones? For they too are his countrymen: the generations of the uncounted dead, breathing through the living, stealing their light from them, the bloodless ghosts of lord and knave, nun and whore, the ghosts of priest and friar who feed on living England, and suck the substance from the future. (p. 575)

Cromwell may, and does, ultimately neutralise those in his path. (He's more merciful than Henry: while the king is happy to have More executed, Cromwell expends much energy trying to save the unrepentant papist from the block.) But when the powers and authorities have been destroyed bodily they live on as ghosts, lingering over Cromwell's new England, hiding in the shadows cast by the Tudors' resplendent majesty.