We comic-book geeks live in a golden age. While the myriad popcorn epics featuring spandex-clad heroes may not always be good, at least they're there to enjoy or deride. Our forefathers were not so lucky. Once upon a time, live-action superheroes were confined to serials, action-comedies, and cheesy television specials.

Richard Donner's Superman (1978), released in the wake of Star Wars (1977), introduced the superhero blockbuster and dominated the eighties with its sequels, but during that decade films and comic books were out of sync: on the page, the Dark Age was dawning with Alan Moore's V for Vendetta (1982-89) and Watchmen (1986-87) as well as Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Batman: Year One (1987).* Tim Burton's Batman (1989), the first really serious superhero film, changed that and kicked off the first wave of comic-book adaptations. (The last film in the series, 1997's Batman & Robin, killed off that wave as well as its own franchise.)

Twenty-odd years on, what was highly revisionist at the time has become 'classic'. The plot begins with Batman still a rumour, scoffed at by the less superstitious of Gotham's criminals. The new district attorney, Harvey Dent (Billy Dee Williams), is preparing to challenge the criminal empire of Carl Grissom (Jack Palance), who is struggling with his overly ambitious lieutenant Jack Napier (Jack Nicholson). Grissom double-crosses Napier, sending him to raid a chemical plant at night and ordering corrupt policeman Eckhardt (William Hootkins) to ambush Napier's men. In the ensuing struggle, Batman disarms Napier, who falls into a vat of green acid and is believed dead.

Napier, however, has miraculously survived both the acid and the ensuing botched plastic surgery ('You understand that the nerves were completely severed, Mr Napier. You see what I have to work with here...') and becomes the villainous Joker in the film's strongest and most iconic scene. After murdering Grissom, he plots to poison Gotham City's hygiene products with Smilex, which will kill the victim while fixing their face in a horrid rictus grin, in the run-up to the city's bicentennial celebrations. (Incidentally, this provides an excellent way to guess at Gotham's location: with a foundation date of 1789, the city is presumably in Ohio, the Great Lakes region, or the north-eastern Atlantic coast.) The Joker also pursues photographer Vicki Vale (Kim Basinger), who is dating wealthy Bruce Wayne (Michael Keaton).

It's a Joker picture, then, even more so than The Dark Knight (2008): Nicholson takes top billing, and Batman functions almost solely as his foil. The focus on the Joker's origin sets the 1989 film apart from the latest Christopher Nolan picture, which has Batman's nemesis appear from nowhere. Giving a definitive origin story for the Joker was controversial among fans (Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore had given a possible, but deliberately ambiguous origin the previous year). But it works: Nicholson's Joker is a crazed villain even before being disfigured (his pre-murder one-liner, 'Have you ever danced with the devil in the pale moonlight?', goes back to his ordinary criminal days), suggesting the Joker is merely a useful persona.

Nicholson gets the best setpieces, too, the most famous perhaps his dance routine desecrating an art gallery to the sounds of Prince's 'Partyman' supplied by a boombox-carrying goon ('I am the world's first fully functioning homicidal artist!'). The actor goes all out on the craziness, and while Nicholson's shtick can be irritating - witness his horrendous overacting almost derail The Departed (2006) - it's perfect here. Granted, I still prefer Heath Ledger's funnier, more anarchic, better-acted take on the role, but Nicholson's Joker, unlike previous live-action iterations simply a ruthless mass murderer, is very good.

That brings us to the film's darkness, infamous in 1989. Again, The Dark Knight has one-upped Batman's on-screen nastiness but not, I think, the earlier film's attitude. Whatever you may say about Christopher Nolan's films - cold procedurals all of them - he tends to choose scripts that ultimate believe in and reward goodness and humanity (as The Dark Knight does repeatedly in its last half-hour). Not so in Batman: here we have a hero who kills off henchmen like there's no tomorrow and, in the film's climax, defeats his opponent with a highly questionable move. If The Dark Knight is willing to show a great deal more darkness, Batman ultimately has a more pessimistic view of the world.

The casting of Keaton, a well-known comedian, was greeted with scepticism, but he is a revelation in the role. Christian Bale is a closer fit to the character's physical description in the comic books, but his Bruce Wayne is nothing but a mask, ultimately shallow, while Batman is his real personality. That works, sure, but Keaton's Wayne - a shy, ordinary man in a mansion he barely knows - is much easier to empathise with. We'd never suspect this nice guy of being Batman, so when he picks up a poker, screaming 'You wanna get nuts? Come on! Let's get nuts!' at the Joker it really works. Keaton's Batman cares about people, whereas Bale's Batman often seems to be quite ready to burn down half of Gotham to get at the Joker. (No-one would do that to Burton's Gotham: a Gothic excess of spires and gargoyles where the Nolan films offer the atmosphere of a techno-thriller, it's just too gorgeous to destroy.)

Despite everything, though, it's not a great film. The plot is functional at best, Basinger is phoning it in, and the action scenes are not quite top-notch. If I like Batman, it's as a radically different vision to the Miller-Nolan school of Batman as man become symbol, brutally disregarding the limitations of his body: in the Millerverse, if Batman's chest had been a mortar, he'd burst his hot heart's shell upon it. Keaton's Batman is defiantly human, struggling with relationships and self-doubt, and he's all the stronger for it.

*With the benefit of hindsight, Moore easily emerges as the greater of the two, but the jury is still out, I think, on who had the greater cultural impact.

Showing posts with label Batman. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Batman. Show all posts

Friday, 14 October 2011

Gotham City always brings a smile to my face

Labels:

Batman,

blockbuster,

comic books,

Gothic,

superheroes

Friday, 16 September 2011

Gotham in ink

Hollywood loves comic books.

This is not surprising: the big comic-book films of the last years – titles

like X-Men: The Last Stand, 300, Spider-Man

3, Iron Man, Wanted, and now The Dark

Knight – have made mountains of cash for the studios. Even a supposed

underperformer like Superman Returns

grossed $391m world-wide and, to absolutely no-one's astonishment, a sequel

(or, rather, the obligatory re-boot) is in the making.

The new films

didn’t just make money; they also won over the dark kingdom of professional

criticism, none more so than Christopher Nolan’s Batman films, Batman Begins (2005) and The Dark Knight (2008). The American

star critic Roger Ebert speaks for many of his peers when he calls The Dark Knight 'a haunted film that… becomes an engrossing tragedy'. Alas, Ebert also claims that '"Batman" isn't a comic book anymore' and that the film 'leaps beyond its

origins'. Wrong, Roger. What Christopher Nolan did – more than previous

Bat director Tim Burton, and in stark contrast to Joel Schumacher, the

perpetrator of Batman Forever and Batman and Robin – was to take the comic

books seriously; he picked up the themes that permeate the Dark Knight’s

universe and translated them to the big screen.

It's pretty much universally acknowledged that Batman is cool. The character is the ultimate adolescent fantasy: a millionaire playboy who spends his nights beating criminals to a pulp with his bare fists. At the same time, he has no superpowers (unlike most of the Justice League) and relies on intelligence and preparedness. But it's not, I think, that he is particularly relatable: Superman's feelings are much more plain, and the Man of Steel, though an alien, has a much more 'normal' family background as a Kansas farmboy. Batman, like his city, is something of an enigma, and it's no surprise that Christian Bale has portrayed him as a closed character, expressive only in the masks he puts on (Bruce Wayne the celebrity businessman, and Batman the crimefighter). His attraction lies, rather, precisely in his total disappearance into the symbol of Batman.

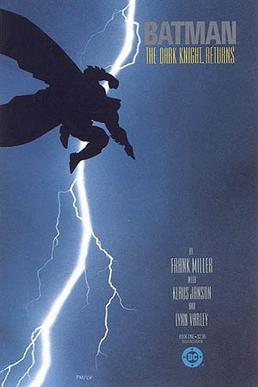

If you

enjoyed the Nolan flicks, you might love the source material, for instance the

classic Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

by Frank Miller (1986). Miller's a funny chap. These days he's a millionaire

after the success of the movie versions of his comics Sin City

and 300. He was also the author of the rumoured Holy Terror, Batman!, a book

of 'propaganda' (quoth Miller, no kidding) in which the Caped Crusader was to battle Osama (a project that has now been scrapped, for reasons that should be somewhat obvious), and of All Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder,

which was released to richly deserved universal derision.

In The Dark Knight Returns a fifty-something Bruce Wayne decides he must

don his cape once more, and Batman's return draws back both old

friends and enemies. Returns is a

wonderful exploration of the Batman and what he means both to Gotham

and to Bruce Wayne, but subtlety is not Frank Miller's forte, and many of the writer's later obsessions are present in embryo here. All the same, this bold

vision of a darker Batman has been hugely influential. Miller's own Batman: Year One tells the story of how

Bruce first invented the Batman persona to inspire fear among the criminals preying

on Gotham. Year One is the inspiration for Batman

Begins, and a jolly good comic-book it is; David Mazzucchelli’s grim and

realistic art (contrasting with Miller's own fluid, exaggerated style) complements the writing perfectly.

Another

classic is Batman: The Killing Joke by British comic-book legend and Churchillian historian Alan Moore. Essentially a dark and disturbing story

about the Joker and madness as escape from a maddening reality, The Killing Joke is the comic-book Heath

Ledger read in preparation for his awe-inspiring performance in The Dark Knight. And Ledger certainly

did portray the Joker as the homicidal sociopath Moore outlined – yet I cannot help feeling

that Ledger actually does more with the character, transcending and

excelling the comic-book original. Nevertheless this is the classic Joker story that uncannily makes you pity the villain (though whether that's a good thing I'll leave to you to decide - The Killing Joke is best read as the Joker's creation of multiple pasts, his own identity being supremely unstable).

There are

villains galore in Batman: The Long

Halloween and its follow-up, Batman:

Dark Victory by Jeph Loeb (writing) and Tim Sale (art), an epic crime saga,

murder mystery, and re-telling of Batman's early career in two parts. 'I

believe in Gotham City', are Bruce Wayne’s opening words, and it is in full

Godfather mode that Loeb tells the story of the Falcone crime empire and how

three men – James Gordon, an ambitious District Attorney named Harvey Dent, and

the Batman – try to conquer crime in Gotham. If this sounds a lot like The Dark Knight, that's because Nolan’s

recent blockbuster is obviously inspired by Loeb, including the tragic journey

of Harvey Dent; these two tales are also among the personal favourites of actor

Christian Bale. Dark Victory

introduces the reviled Robin the Boy Wonder, and the character actually manages

to be bearable – testament to Loeb's considerable writing skills. Both books are overloaded with tropes, but that needn't be a bad thing.

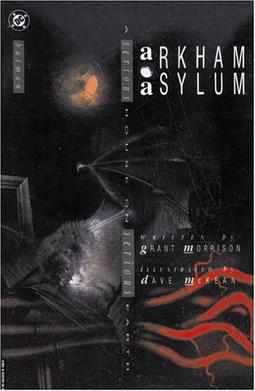

Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth is

where virtually all of Batman's enemies are locked up. But one day the inmates

take over the asylum, and they only have one demand: Batman must come and visit

them. Arkham Asylum is a descent into

madness that places Batman’s stay in the institution alongside the story of the

rise and fall of Amadeus Arkham, the founder of the asylum. A 'comic book' that's not particularly funny, Arkham Asylum is a profound

and disturbing exploration of insanity, drawing on sources from Lewis Carroll to Aleister Crowley (the subtitle is drawn from Philip Larkin). Dave McKean’s art deserves special

mention for being terrifyingly weird and taking Grant Morrison’s excellent

writing to a whole new level: in almost every panel dark shadows lurk around characters whose own edges are ill-defined, blending into the enveloping madness.

Note: This is an updated version of an article originally written in 2008, hence the outdated references.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)