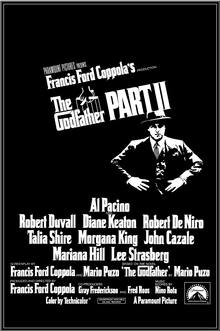

Sixteen years passed between the universal acclaim of

The Godfather Part II and its belated epilogue.

In the meantime, Francis Ford Coppola struck gold again with

Apocalypse Now, but at the price of an infamously gruelling shoot. In the eighties, the director suffered a long string of flops and misfires, bottoming out with

Tucker: The Man and His Dream. Exhausted and close to bankruptcy, Coppola finally accepted Paramount Pictures' long-standing offer to direct a third film in the series that had put him on the map.

The circumstances surrounding that film, finally released in December 1990, were a recipe for disaster.

The Godfather Part III was a blatant cash grab. It was missing Robert Duvall, who declined to return after being offered too small a fraction of Al Pacino's salary. Most ominously, Coppola wanted the film to be a smaller-scale epilogue titled

The Death of Michael Corleone, but the studio insisted on the

Part III title.

The film's reception was far less glowing than its predecessors', but it was usually considered flawed, tacked-on and inessential rather than a true disaster: the first film in the series to include real, substantial misjudgments, but not bad

per se. The temptation is to declare that if only it wasn't a part of the

Godfather series and derived unearned canonisation from them, we should hail it as a pretty good gangster picture. But that doesn't really stand up to scrutiny. Like Michael Corleone himself

Part III is obsessed with the events of the previous films and derives all its substance from them. It's a mood piece that meditates on the first two films, exploring how they resonate two decades down the line and whether there is any escape from the cycle of violence. I'm partial to that.

It certainly doesn't help, though, that

The Godfather Part III opens with its worst scene, and therefore the weakest scene in the whole franchise. In 1979 Michael (Al Pacino, barely recognisable), pushing sixty and still at the head of the Corleone family, receives an award from the Catholic Church in return for a donation of a hundred million dollars for the needy of Sicily. His ex-wife Kay (Diane Keaton) wants him to allow his son Anthony (Franc D'Ambrosio) to quit his law degree and become a professional singer, but Michael is reluctant. Meanwhile, he has to settle a dispute between crime lord Joey Zasa (Joe Mantegna) and Vincent Mancini (Andy García), a choleric low-level mobster and illegitimate son of Santino Corleone.

It's a clusterfrak of poor choices, beginning with the copious use of footage from the first two films. Generally, the things wrong with this scene will continue to bog down the film, but nowhere else are they present in such concentrated form. There's the infodumping introduction of new characters (George Hamilton as family lawyer B.J. Harrison, John Savage as Andrew Hagen, Eli Wallach as affable ageing gangster Don Altobello), the pointless cameos from Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) to Enzo the baker (Gabriele Torrei) - who

actually refers to himself as 'Enzo the baker', for goodness' sake - , and the awful acting and dialogue: the worst in the whole film, in fact, from Keaton's worst work as Kay to a gut-churning 'flirting' scene between Vincent and Mary Corleone (Sofia Coppola).

The film picks up in a tense, profane confrontation between Vincent and Zasa that ends with a savaged ear instead of the peace Michael demands. From there, it gets better: Vincent, attacked in his flat by thugs who threaten his girlfriend Grace Hamilton (Bridget Fonda) and backed by Michael's sister Connie (Talia Shire), champs at the bit to be allowed to strike back at Joey Zasa. At a meeting of the Commission in Atlantic City, Michael pays out his partners' shares in the casino business and dissolves his relationships between them but Joey Zasa, who receives nothing, leaves in anger. Shortly after, the meeting is attacked and most senior gangsters machine-gunned. Michael, who survives uninjured, suffers a diabetic stroke from stress. While he's recovering, Vincent assassinates Joey Zasa with the endorsement of Connie and Al Neri (Richard Bright).

In the film's third act the family relocates to Sicily, where Anthony is due to give his operatic debut in a performance of

Cavalleria rusticana. Michael, eager to invest in legitimate enterprises, sees his efforts to control the board of a European real estate company blocked by a shadowy cabal of gangsters, bankers and senior churchmen, and feels forced to order one last round of blood-letting that he no longer has the strength for. He offers Vincent leadership of the family, on condition that the latter end his romance with Mary. But the enemy behind all the machinations against him has ordered a Sicilian assassin (Mario Donatone) to go to the opera and take Michael out once and for all.

At its heart

The Godfather Part III is about redemption. Michael Corleone makes one last attempt to make the transition from crime to legitimate business and atone for ordering his brother's death, and he fails. The theme of being unable to shake off the sins of the past no matter how hard one tries explains and, I at least would argue, justifies the film's obsession with its predecessors, its modest ambition to be no more than an epilogue. It also accounts for the sheer amount of religious themes and Catholic iconography strewn all over the film: religion played a part in previous installments, but it is here, between rosaries, Madonnas and important scenes set in the Vatican, that Catholicism is really foregrounded.

In the film's signature scene - in which, unfortunately, we can see the actors' breath, making it tremendously obvious it was filmed somewhere rather colder than southern Italy in the summer - Michael visits Cardinal Lamberto (Raf Vallone) because he needs his assistance against Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly). Overcome by the compassion of a man he later calls 'a true priest', Michael tearfully confesses his sins, but realises he will not repent. 'Your sins are terrible, and it is just that you suffer,' Lamberto says: 'Your life could be redeemed, but I know that you don't believe that. You will not change.' And then, with an infinite sadness, he does his job:

'Ego te absolvo in nomine Patris...'

Michael tries to atone for the sins of his past, but he also wants to ensure a future for his family free of that evil. He struggles with the unconditional love Anthony and Mary display towards him, and tries to repair his relationship with his ex-wife, who loves and dreads him. The problem is that all this material, much of which is the heart of the film, does not work

at all. Keaton has the worst dialogue in the film -

again, one might say after Part II. Her job has always been to state the films' message in no uncertain terms, at the expense of a character that has sounded increasingly self-righteous and whiny. Saddled with the sort of material she's served here, Keaton gives her worst performance in the franchise.

The other infamous piece of acting is of course Sofia Coppola, cast by her father after Winona Ryder dropped out at the last minute. Coppola, unfortunately, is quite as awful as her detractors say. The film pretty much dies every time she's onscreen, which spells trouble since the climax hinges on her relationship with Pacino. The problem, though, isn't merely nepotism - the

Godfather series had always provided gainful employment for the whole Coppola family, not generally to the films' detriment. Sofia Coppola is simply saddled with having to portray the weakest character in the weakest script of the series. Ryder would almost certainly have been better, but I cannot imagine a

good performance of this character.

Two facts negate the obvious assumption that the Puzo-Coppola team simply cannot write women. Firstly, D'Ambrosio's Anthony is also a poor character. Secondly, there's Talia Shire, the director's sister and living refutation of the theory that the series' problems are caused by rampant nepotism. Shire had always given strong performances, but in Part III she moves to the centre of the cast, and Connie becomes magnificent as a result: passionate about the family, she has gained an austere ruthlessness that leads her to back the brutal Vincent. The script also makes her Don Altobello's goddaughter, which lends intense poignancy to the scene in which she gives him a box of cannoli for his birthday.* ('Sleep, godfather.')

García is very good too, with the exception of his leaden romance scenes with Sofia Coppola. A murderous thug and little else, his Vincent Mancini is a crucial element in the process of self-demythologisation that began with

The Godfather Part II. He's difficult to like and admire, but tremendously easy to fear. Similarly, the shady Don Lucchesi (Enzo Robutti) doesn't look like a film character: he resembles the 'important' people my overly status-conscious bourgeois grandparents used to invite to family functions. He's more accountant than glamorous gangster, but no less pitiless and deadly for that.

The film's direction is a tick less good than its predecessors' and Carmine Coppola's score makes me miss Nino Rota, who was unable to return on account of being dead. But as pure spectacle

The Godfather Part III still doesn't disappoint. For starters, the production design is absolutely gorgeous. Art director Alex Tavoularis, joining his brother and series veteran Dean Tavoularis, leaves the somewhat realistic look of Part II far behind and goes for Baroque spectacle: red curtains, gold, daggers, and religious imagery. That pays off in the climactic opera scene, an aural and visual feast that is not the series' most effective sequence but certainly its most spectacular. It almost manages to make you forget a clumsy

dénouement marred by abysmal old-age make-up.

The fact of the matter is that I kind of love

The Godfather Part III. Yes, it has some fairly horrendous flaws, unlike its near-perfect brethren. And no-one could accuse it of being essential: without it, the saga of Michael Corleone would be no less complete. But beside the spectacle, the film is marked by a deep human yearning for peace, an end to a seemingly neverending cycle of violence. It isn't optimistic in that sense, but it doesn't need to be: the hope for peace itself matters. As long as we have that (as Vincent and Connie do not), all is not lost.

*The last time I watched The Godfather Part III with friends who hadn't seen it before, I made and brought cannoli. I recommend doing that.

In this series: The Godfather (1972) | The Godfather Part II (1974) | The Godfather Part III (1990)