The Empire Strikes Back (1980) started a Star Wars tradition of confusing and alienating audiences that has become pretty much synonymous with the franchise over the years. For despite being advertised by just that four-word title ahead of release (see the poster), the film's opening crawl instead referred to it as Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back. A science-fiction franchise had suddenly become a humongous 'saga' that had apparently and inexplicably begun on its fourth installment. The course had been set for a bright future of crippling continuity errors and, eventually, a leaden prequel trilogy - a curious achievement for what is clearly and unequivocally the best film in the series.

This doesn't quite seem to have been the intention right at the start: some of the most distinctive plot elements of Empire (SPOILERS) were only introduced by George Lucas after he was disappointed by a first draft, written by veteran space opera and planetary romance writer Leigh Brackett in the final stages of her battle with cancer. In reworking the script Lucas came up with the film's darker direction and the no-longer-stunning plot twist that Darth Vader is (well, claims to be, as far as Empire is concerned) Luke Skywalker's father. This in turn led to a backstory expansion in which Anakin Skywalker was Obi-Wan Kenobi's apprentice before being seduced by the Emperor (now a user of the dark side of the Force and no longer a mere politician, though not yet Ian McDiarmid), opening the possibility of a prequel trilogy. This newer, bigger story also retroactively turned Obi-Wan into a liar who manipulated Luke into helping him and attempting to blow up his own father along with the Death Star, but really, in the continuity mess of even the core Star Wars canon that's small change.

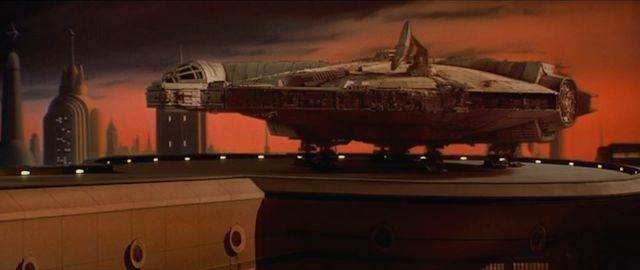

The story: forces of the Rebel Alliance, including all the surviving

heroes of the previous film, have constructed a base on the inhospitable

ice world of Hoth. Before long, though, they're discovered by the

Imperial fleet of Darth Vader. The rebels manage to hold off the

Imperial ground assault long enough to pull off a successful withdrawal

but Han Solo and Leia Organa (Harrison Ford and Carrie Fisher) fail to

get away from the Imperials because of the Millennium Falcon's broken

hyperdrive. Hiding first in a deadly asteroid field and then fleeing to

Cloud City, where Han's old frenemy Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee

Williams) runs a mining operation, they're hunted by Vader's fleet as

well as a bunch of bounty hunters.

Meanwhile, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) follows a vision of his one-time mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi to the swamp world of Dagobah. There, Obi-Wan's own teacher, the diminutive and ancient Jedi master Yoda (Frank Oz), instructs him in the ways of the Force, teaching him to become a Jedi knight himself. Before he can complete his training, though, Luke has a premonition of his friends in danger. Worried by Yoda's warnings but ultimately unable to ignore Han and Leia's suffering, Luke races off to Cloud City, his training unfinished, to save his friends from Vader's clutches.

The final script, written by Lawrence Kasdan based on Lucas's second

draft, is fantastic: it zips by, the necessary exposition is handled

supremely well (for a film that expands the story so much, there are

very few scenes of character simply sitting down and talking), and the

dialogue is much punchier and more contemporary than Lucas's

self-conscious throwback pulp stylings in Star Wars. Those work too, and having lavished praise on Lucas's script I'm not about to change my mind. But what worked for Star Wars wouldn't work for Empire:

where the first film was all about roughly sketching a world of

intergalactic adventure and a stark battle between good and evil, the

second installment fleshes out that world and develops its characters

from old-school sci-fi archetypes into, well, people.

(Even so, let's not beat about the bush: the timeline of Empire is pretty much impossible (which isn't to say Star Wars

fans haven't made up elaborate excuses for the film). In the time that

Han and Leia take to run from Hoth to Bespin, the Empire hot on their

heels (a few standard days at most), Luke goes to Dagobah, meets Yoda

and gets a significant chunk of Jedi training done (weeks at least).

Impossible in terms of realism, to be sure. But in story terms, it

works: Luke's less action-packed, more contemplative and philosophical

scenes alternate effectively with scenes of danger involving Han and

Leia. Time has always moved at the speed of plot in Star Wars, and I'm

happy to give the film a pass here.)

The new and improved dialogue does a lot for the characters, and it's a much better fit for some of the actors. Carrie Fisher's Leia is even more acerbic this time around, and Kasdan gives her a couple of fantastic zingers: 'Would it help if I got out and pushed?' when Han's rust bucket won't get going, or the wondrous 'You don't have to do this to impress me' as he heads into an asteroid field. That brings us neatly to the problem of Leia in Empire: she's reduced from the aristocratic leader of Star Wars to playing the straight man to Han Solo's antics. Which is enjoyable, but leaves the character a little thin. Ford is freer and looser this time around (thanks, no doubt, to a more cooperative director), and Hamill is - well, I like him less in Empire than in either Star Wars or Jedi, but his final scenes in the film are terrific, no doubt about it.

In the smaller roles there's so much goodness: I'm a particular fan of

all the pitiable Imperial officers who must achieve impossible

objectives, or be murdered by Vader. (There is, in general, a lot of

excellent bleak humour in the scenes aboard the Executor). An

easy favourite is Kenneth Colley's put-upon Admiral Piett, a man who

through long practice has become really good at ignoring people being

force-choked right next to him, and actually makes it out of Empire alive.

But Julian Glover's General Veers, a man who clearly enjoys nothing

more than (a) sneering and (b) stomping on infantry with his enormous

armoured tank, is a wonderful mini-villain too. On the other side, I'm a

big fan of Bruce Boa's General Rieekan, who radiates a slightly gruff

but likeable authority on Hoth.

That's all well and good, but let's get to the best character in Empire, shall we? Because Yoda is that. I still love the reveal that the cackling imp who rummages through Luke's equipment is, in fact, a powerful Jedi master. He's a perfect embodiment of the film's thesis that the Force as a mystical ally can help the weak triumph over the strong, that it makes the underdog's victory over all the Empire's might a real possibility. He injects a warm sense of wonder about the Force, a humanist love of people over cold military power ('luminous beings are we, not this crude matter') and a yearning for peace ('wars not make one great'). And he does it all with humour (Frank Oz's outraged delivery of 'Mudhole? Slimy? My home this is!' cracks me up every time), dignity, and real authority. I understand that for Hamill weeks of sharing the scene with a puppet weren't too much fun, but the result is spellbinding.

(You know who sucks in Empire, though? Obi-Wan Kenobi. He does nothing but deliver some exposition and whinge about stuff. And Alec McGuinness, whose wry self-amusement worked wonders in Star Wars, is really phoning it in this time around. It's a waste.)

Lucas didn't do much to polish Empire in the special editions and home video releases. The major exception - one Star Wars fans don't object to, curiously - is Ian McDiarmid portraying the emperor (instead of Elaine Baker with digitally inserted chimpanzee eyes and Clive Revill doing the voice). Even better is that you don't need the despecialized edition to appreciate the special effects, which Lucas, despite his reputation, has only ever tweaked to remove errors. And they're wonderful. Terrifying stop-motion AT-ATs marching mercilessly across the frozen landscape while seemingly mosquito-sized rebel snowspeeders flit around them, a city floating above the clouds, a star destroyer adrift after a hit from the ion cannon. My absolute favourite, though, is the tauntauns. The puppet work in close-ups is very good, but I adore the stop-motion used in wide shots even more. The creatures move in an alien yet believable way, and they've got an almost Harryhausenesque amount of personality. (Plus great sound design, but in Star Wars that goes without saying.)

In the hands of Irvin Kershner Empire is a bit more life-sized than Star Wars, its characters just as mythical but a little less archetypal. By the second film, the series was starting to fill out its world, developing its characters (who are starting to feel like people we know and like instead of The Naive Young Hero, The Rogue, The Damsel, The Mentor, &c.) and breaking free from its '30s forebears. Put another way, Empire feels much less like Flash Gordon fan-fiction and much more like the work of people who suspected that more than just paying homage to them, Star Wars would utterly displace the pulp serials of yore in the public imagination. With a compelling story involving great characters, terrific setpieces and top-notch craftsmanship, Empire provides a good argument that Star Wars' place as a pop culture juggernaut is fully and legitimately earned.

Showing posts with label blockbuster. Show all posts

Showing posts with label blockbuster. Show all posts

Wednesday, 18 November 2015

Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter

Saturday, 3 October 2015

Hokey religions and ancient weapons

Star Wars is the first blockbuster franchise I loved. Whether it was for lack of interest or because I preferred books, I didn't watch a lot of films when I was a kid. Star Wars blew me away. It opened up my imagination to a whole world of pulp science fantasy and started me off on a geeky obsession that has never gone away, attested to by shelves of tattered, treasured Expanded Universe novels.

Admittedly the Star Wars film I'm talking about was The Phantom Menace, and I only caught up with the first film in the series on VHS a few months later. I loved them both - I suppose I wasn't the most discriminating eleven-year-old. With time I learnt that fandom orthodoxy frowned on The Phantom Menace but loved Episode IV: A New Hope, as Lucas retitled the 1977 film on its re-release. And at least as far as Episode IV is concerned, the fandom is right. The film is ace: a total matinee delight that may not be the same technical marvel it appeared in 1977, but holds up just about perfectly all the same.

(A quick note: the basis for this review is the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars, a fan-made high-definition version of the original trilogy that attempts to restore the films as they originally appeared in cinemas, instead of the 1997 'special editions' (plus subsequent additions and changes) that modern Blu-ray copies are based on - fan-made because Lucas infamously wouldn't release anything except his new and allegedly improved versions in high-definition.

The thing is, the special editions are how I first experienced Star Wars, and I imagine it's the same for a lot of people who weren't around in the seventies and early eighties. But because of all the criticism the special editions get in fan circles - Han shot first et cetera ad nauseam - I was aware of most of the changes. They're pretty minor, by and large: CGI critters instead of practical effects, mostly, and a weird floating Jabba who pops in to utter the exact same threats Greedo did hardly five minutes earlier. But there's one exception: a scene near the end, in which Luke meets his old Tattooine mate Biggs Darklighter on Yavin 4, which ended up on the cutting room floor in the original release but was restored for the special editions. And considering the banter between the pilots during the Death Star attack is damn weird without that scene - they're talking as if they've known each other all their lives, which isn't indicated in anything we've seen before - restoring it was clearly the right decision.)

The story: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a nineteen-year-old living on the backwater planet of Tatooine, longs to be released from his tedious life on his uncle's moisture farm and go off to become a starfighter pilot. Tasked with cleaning two new droids his uncle has bought (Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker), Luke discovers they're carrying a message of vital importance from Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), which they're tasked with relaying to a retired general and current hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that just like himself, Luke's father was a Jedi Knight, a fighter for good drawing on the mystical Force killed by the evil Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), and perhaps Luke would like to accompany him to leave Tatooine and join Princess Leia in their rebellion against the evil Galactic Empire?

This is understandably too much for Luke to take in straight away, but his decision is made for him: Imperial stormtroopers attack his home, massacring his aunt and uncle and forcing Luke, Obi-Wan and the droids to flee. In the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, they hire smuggler Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his towering alien sidekick Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), who are themselves in a lot of trouble with some unsavoury elements. Together, this motley crew head to Leia's homeworld of Alderaan, only to find the whole planet obliterated by something that decidedly isn't any moon...

Everyone knows that story, but it's perhaps worth pointing out the ways in which the plot of the 1977 film isn't the story of the Star Wars franchise that developed after it, simply because George Lucas and his collaborators hadn't settled on those things yet. Certain family relationships don't yet exist; Obi-Wan unambiguously hates Vader's guts; the Jedi are treated as a myth of the ancient past and the existence of the Force is explicitly denied by several characters, although in the course of the film it seems to become the official creed of the Rebel Alliance; the emperor is a distant, unseen figure; Vader is only one of the empire's henchmen and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) orders him around, while others openly insult his religious beliefs.

It's so simple and archetypal (little wonder, since Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces): a wide-eyed audience stand-in who dreams of seeing something of the world, be a hero and rescue a beautiful princess; a wise old mentor, not long for this world; a charming rogue who learns to value friendship over money; a dastardly villain; and a character who, yes, is at this point still kind of an old-school damsel in distress, but at least has her own mind, some justifiable complaints about her ill-planned rescue, and ideas for how to do a better job. But it takes skill to do this stuff well, and Star Wars does it extremely well.

The script isn't usually given the amount of credit it's due, but it's among the reasons for the success of Star Wars and its immediate ability to capture the imagination. Lucas wrote the thing more than once, never happy with the results, and when Star Wars started filming in Tunisia the screenplay was still unfinished. The process of often sharply critical feedback over several years from Hollywood insiders and Lucas's wife, as well as uncredited dialogue rewrites by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, somehow produced a particular alchemy.

The result is glorious high pulp, instantly quotable and wonderful: "You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy"; "I find your lack of faith disturbing"; "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid"; "Evacuate? In our moment of triumph?"; "The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers", and so on. None of this is remotely how real people talk, but it gives the film an outsized air of adventure and wonder that helps it hit all the high notes.

Then there are the performances. The role of Luke Skywalker at this point is still something of a generic person, but Mark Hamill gets that right: we like and empathise with Luke, and that's what the film needs. The others are allowed to do more, and they're terrific. Alec Guinness forever seems gently amused at being asked to deliver dialogue about Jedi knights and disturbances in the Force, which results in a winning, light performance. Peter Cushing, veteran Hammer Horror vampire hunter, makes for a marvellously icy and authoritative warlord with drive, determination and cruelty to spare.

To me, there are three standouts: Harrison Ford's natural charisma causes him to make the role his own so much that he essentially spun it off into another franchise, as Indiana Jones. Anthony Daniels portrays C-3PO as a self-pitying but fundamentally decent comic foil who gets some of the film's biggest laughs ("Listen to them, they're dying, R2! Curse my metal body, I wasn't fast enough, it's all my fault!") And lastly, David Prowse's physical acting has always been overshadowed by James Earl Jones's voice, but his performance inside the Darth Vader suit is perfect: authoritative and menacing, but very far from emotionless. I adore the scene in which he pauses as he senses Obi-Wan for the first time; it's subtle but all kinds of wonderful.

Star Wars wouldn't be Star Wars without the lovely production design, though: it's chock-full of amazing ideas brilliantly executed. And unlike the second and third prequels, which are full of stuff happening in the background, the first film has the sense to actually briefly focus on the terrific alien suits, grime-covered droids and fossils bleached by the Tatooine suns, giving them each the dignity and two seconds of glory they deserve. (My favourite is and remains the tiny droid skittering away from Chewbacca on the Death Star, beeping in fear.) The film's used-future aesthetic - which belongs exclusively to the good and neutral characters, while the Empire is exquisitely glossy - is wonderfully and consistently realised.

The special effects are extremely good: they look dated, yes, but virtually never unconvincing. The real star is Ben Burtt's sound design, though. From all the mechanical whirring and hissing to Chewbacca's voice and Vader's breathing, the sounds of Star Wars remain instantly recognisable. There's so much high-class craftsmanship here, it really makes you appreciate the often-forgotten art of sound design (and miss it in all the projects that neglect to go beyond mere competence).

So what doesn't hold up? Despite everything, the final film is a bit slight; it zips past having established fairly little of its world beyond rough outlines, and selling some of its character development more through conviction than storytelling logic (Luke's attachment to Obi-Wan, in particular, feels dodgy after so short an acquaintance, especially since he immediately forgets about the people who raised him). The film offers a world of adventure so appealing, it's not surprising people wanted sequels and an enormous expanded universe. But it also feels a little like Star Wars needed those things to round it out, and like, had nothing else ever followed, the film would feel roughly sketched. But if the worst thing I can say about a film is that I want more of its world and characters than it can possibly provide in two hours, well...

Admittedly the Star Wars film I'm talking about was The Phantom Menace, and I only caught up with the first film in the series on VHS a few months later. I loved them both - I suppose I wasn't the most discriminating eleven-year-old. With time I learnt that fandom orthodoxy frowned on The Phantom Menace but loved Episode IV: A New Hope, as Lucas retitled the 1977 film on its re-release. And at least as far as Episode IV is concerned, the fandom is right. The film is ace: a total matinee delight that may not be the same technical marvel it appeared in 1977, but holds up just about perfectly all the same.

(A quick note: the basis for this review is the Despecialized Edition of Star Wars, a fan-made high-definition version of the original trilogy that attempts to restore the films as they originally appeared in cinemas, instead of the 1997 'special editions' (plus subsequent additions and changes) that modern Blu-ray copies are based on - fan-made because Lucas infamously wouldn't release anything except his new and allegedly improved versions in high-definition.

The thing is, the special editions are how I first experienced Star Wars, and I imagine it's the same for a lot of people who weren't around in the seventies and early eighties. But because of all the criticism the special editions get in fan circles - Han shot first et cetera ad nauseam - I was aware of most of the changes. They're pretty minor, by and large: CGI critters instead of practical effects, mostly, and a weird floating Jabba who pops in to utter the exact same threats Greedo did hardly five minutes earlier. But there's one exception: a scene near the end, in which Luke meets his old Tattooine mate Biggs Darklighter on Yavin 4, which ended up on the cutting room floor in the original release but was restored for the special editions. And considering the banter between the pilots during the Death Star attack is damn weird without that scene - they're talking as if they've known each other all their lives, which isn't indicated in anything we've seen before - restoring it was clearly the right decision.)

The story: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), a nineteen-year-old living on the backwater planet of Tatooine, longs to be released from his tedious life on his uncle's moisture farm and go off to become a starfighter pilot. Tasked with cleaning two new droids his uncle has bought (Anthony Daniels and Kenny Baker), Luke discovers they're carrying a message of vital importance from Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), which they're tasked with relaying to a retired general and current hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness). Obi-Wan reveals to Luke that just like himself, Luke's father was a Jedi Knight, a fighter for good drawing on the mystical Force killed by the evil Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones), and perhaps Luke would like to accompany him to leave Tatooine and join Princess Leia in their rebellion against the evil Galactic Empire?

This is understandably too much for Luke to take in straight away, but his decision is made for him: Imperial stormtroopers attack his home, massacring his aunt and uncle and forcing Luke, Obi-Wan and the droids to flee. In the seedy spaceport of Mos Eisley, they hire smuggler Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and his towering alien sidekick Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), who are themselves in a lot of trouble with some unsavoury elements. Together, this motley crew head to Leia's homeworld of Alderaan, only to find the whole planet obliterated by something that decidedly isn't any moon...

Everyone knows that story, but it's perhaps worth pointing out the ways in which the plot of the 1977 film isn't the story of the Star Wars franchise that developed after it, simply because George Lucas and his collaborators hadn't settled on those things yet. Certain family relationships don't yet exist; Obi-Wan unambiguously hates Vader's guts; the Jedi are treated as a myth of the ancient past and the existence of the Force is explicitly denied by several characters, although in the course of the film it seems to become the official creed of the Rebel Alliance; the emperor is a distant, unseen figure; Vader is only one of the empire's henchmen and Grand Moff Tarkin (Peter Cushing) orders him around, while others openly insult his religious beliefs.

It's so simple and archetypal (little wonder, since Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces): a wide-eyed audience stand-in who dreams of seeing something of the world, be a hero and rescue a beautiful princess; a wise old mentor, not long for this world; a charming rogue who learns to value friendship over money; a dastardly villain; and a character who, yes, is at this point still kind of an old-school damsel in distress, but at least has her own mind, some justifiable complaints about her ill-planned rescue, and ideas for how to do a better job. But it takes skill to do this stuff well, and Star Wars does it extremely well.

The script isn't usually given the amount of credit it's due, but it's among the reasons for the success of Star Wars and its immediate ability to capture the imagination. Lucas wrote the thing more than once, never happy with the results, and when Star Wars started filming in Tunisia the screenplay was still unfinished. The process of often sharply critical feedback over several years from Hollywood insiders and Lucas's wife, as well as uncredited dialogue rewrites by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, somehow produced a particular alchemy.

The result is glorious high pulp, instantly quotable and wonderful: "You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy"; "I find your lack of faith disturbing"; "Hokey religions and ancient weapons are no match for a good blaster at your side, kid"; "Evacuate? In our moment of triumph?"; "The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers", and so on. None of this is remotely how real people talk, but it gives the film an outsized air of adventure and wonder that helps it hit all the high notes.

Then there are the performances. The role of Luke Skywalker at this point is still something of a generic person, but Mark Hamill gets that right: we like and empathise with Luke, and that's what the film needs. The others are allowed to do more, and they're terrific. Alec Guinness forever seems gently amused at being asked to deliver dialogue about Jedi knights and disturbances in the Force, which results in a winning, light performance. Peter Cushing, veteran Hammer Horror vampire hunter, makes for a marvellously icy and authoritative warlord with drive, determination and cruelty to spare.

To me, there are three standouts: Harrison Ford's natural charisma causes him to make the role his own so much that he essentially spun it off into another franchise, as Indiana Jones. Anthony Daniels portrays C-3PO as a self-pitying but fundamentally decent comic foil who gets some of the film's biggest laughs ("Listen to them, they're dying, R2! Curse my metal body, I wasn't fast enough, it's all my fault!") And lastly, David Prowse's physical acting has always been overshadowed by James Earl Jones's voice, but his performance inside the Darth Vader suit is perfect: authoritative and menacing, but very far from emotionless. I adore the scene in which he pauses as he senses Obi-Wan for the first time; it's subtle but all kinds of wonderful.

Star Wars wouldn't be Star Wars without the lovely production design, though: it's chock-full of amazing ideas brilliantly executed. And unlike the second and third prequels, which are full of stuff happening in the background, the first film has the sense to actually briefly focus on the terrific alien suits, grime-covered droids and fossils bleached by the Tatooine suns, giving them each the dignity and two seconds of glory they deserve. (My favourite is and remains the tiny droid skittering away from Chewbacca on the Death Star, beeping in fear.) The film's used-future aesthetic - which belongs exclusively to the good and neutral characters, while the Empire is exquisitely glossy - is wonderfully and consistently realised.

The special effects are extremely good: they look dated, yes, but virtually never unconvincing. The real star is Ben Burtt's sound design, though. From all the mechanical whirring and hissing to Chewbacca's voice and Vader's breathing, the sounds of Star Wars remain instantly recognisable. There's so much high-class craftsmanship here, it really makes you appreciate the often-forgotten art of sound design (and miss it in all the projects that neglect to go beyond mere competence).

So what doesn't hold up? Despite everything, the final film is a bit slight; it zips past having established fairly little of its world beyond rough outlines, and selling some of its character development more through conviction than storytelling logic (Luke's attachment to Obi-Wan, in particular, feels dodgy after so short an acquaintance, especially since he immediately forgets about the people who raised him). The film offers a world of adventure so appealing, it's not surprising people wanted sequels and an enormous expanded universe. But it also feels a little like Star Wars needed those things to round it out, and like, had nothing else ever followed, the film would feel roughly sketched. But if the worst thing I can say about a film is that I want more of its world and characters than it can possibly provide in two hours, well...

Sunday, 21 December 2014

Battle of the Five Hours

The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies is apparently the shortest of Peter Jackson's Hobbit series, but had you told me it was twice as long as any of the Lord of the Rings films I might well have believed you. The Battle of the Five Armies is, above all, an earnest plea for the importance of structure. It's a film that - after a prologue that feels tacked on from the preceding film - is just an enormous slog, without notable turns, shifts, pauses or high points. It's noisy and epic in its ambitions, while at the same time being utterly inert and tedious.

I should say first, perhaps, that I haven't seen either of the two preceding films. (The release of An Unexpected Journey inspired me to re-read the book, at least.) But if watching the first two installments is necessary to enjoy Battle of the Five Armies, that hardly improves things: Each film in a trilogy, you'd hope, should have a satisfying arc of its own and be enjoyable watched in isolation, especially since they're being released a year apart. This is something, incidentally, that Jackson's own Lord of the Rings trilogy achieves in adapting a single novel that was split into three volumes at the insistence of Tolkien's publisher, even if the writers have to strain mightily to make it happen (especially in The Two Towers, where as a consequence the seams are most obvious). For The Hobbit, Jackson didn't even try.

The plot, what there is of it: The company of dwarves having finally reached the Lonely Mountain, their 'burglar', hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Martin Freeman), steals the Arkenstone from Smaug the dragon (Benedict Cumberbatch). Angered, Smaug flies off to Lake-town and burns it to the ground, but is slain by Bard the Bowman (Luke Evans) in the process. Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage), suddenly freed from the headache of how to get rid of Smaug, refounds the dwarven kingdom of Erebor and, increasingly overcome by the allure of gold, has his followers fortify the entrance before others stake a claim. As indeed they do: Bard arrives with the people of Lake-town to demand the share of the treasure Thorin promised, to help rebuild the town; he is soon joined by the army of King Thranduil of the wood-elves (Lee Pace), who is incensed at Thorin deceiving and escaping him. Thorin's pig-headed refusal to negotiate is backed up when his cousin Dáin Ironfoot (Billy Connolly) arrives with an army of dwarves. Before the sides come to blows, however, a horde of orcs led by Azog the Defiler (Manu Bennett) shows up and much mayhem ensues.

There's also a subplot involving Gandalf and some characters you may remember from the Rings films fighting the necromancer in Dol Guldur, but that takes up all of five minutes.

The Battle of the Five Armies is pretty to look at, no doubt: the wintry surrounds of the Lonely Mountain are a triumph of landscape photography, set design and cinematography. Set in cold northern wastes the Rings films never touched on, The Battle of the Five Armies serves up new, interesting environs. And there are some genuine thrills there, too: Dáin's dwarven phalanx in action is a sight to see, even if the Warhammer-esque blockiness of the dwarf design, which I've never been a fan of, still spoils the view somewhat.

On the downside there are the terrible CGI-enhanced baddies. The Rings films, for all the criticism rightly levelled at them, were heaven for fans of practical effects. The design of the orcs, using masks, prosthetics and make-up, gave the creatures a gross physicality that lined up with the spittle, body odour and vile dietary habits that defined them as fictional versions of the working-class people of Tolkien's patrician nightmares. CGI allows the creation of wonders that old-school effects have never been able to achieve, but the trade-off is still often a lack of heft and weight.

There is no reality and thus no threat to these orcs, snarl as they might. Compare the magnificant fight between Aragorn and Lurtz in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) to Thorin's endless, mind-numbingly boring battle against Azog in this one, and despair. (A similar scene, in which Legolas leaps along a collapsing walkway like Super Mario, caused peals of laughter to ring around the auditorium.) With the Hobbit films (let's just boldly assume this problem affects the previous two films as well), Jackson has gone full-on Phantom Menace.

The film is hopelessly dragged down is its sheer length, forced by the mercenary decision to turn The Hobbit not into one, nor two, but three feature-length films. Reverse that decision, and this entire film could be wrapped up in the 45 minutes the material merits; the enormous structural problem would disappear; the fact that the nominal protagonist has nothing to do would be much less noticeable. Lengthy, pointless scenes involving cowardly Alfrid (Ryan Gage), in which jokes about such humorous subjects as men wearing women's clothes are expected to provide comic relief, could be cut, as could a bizarre psychedelic sequence involving Thorin among Smaug's gold that shows us Jackson using the freedom granted by a near-total absence of plot to baffling effect.

But the film's length isn't its only problem: indeed some fairly important aspects of the book are passed over in downright indecent haste (the arrival of Beorn and the eagles), while threads are left dangling in other places (we're left to assume, for example, that Dáin and the elves defeated the orc army after its leaders are killed elsewhere, but the film doesn't see the need to spell out the outcome of the titular battle). There's the film's uninspiring visual language too: where Rings had stunning images, even if they were often an homage to greater works, The Battle of the Five Armies offers little to look at, as if Jackson was overcompensating for his tendency to gawk at his sets.

Anyway, I'm glad this new trilogy is over, and sort of pleased Jackson doesn't have the rights to any more of Tolkien's works.

I should say first, perhaps, that I haven't seen either of the two preceding films. (The release of An Unexpected Journey inspired me to re-read the book, at least.) But if watching the first two installments is necessary to enjoy Battle of the Five Armies, that hardly improves things: Each film in a trilogy, you'd hope, should have a satisfying arc of its own and be enjoyable watched in isolation, especially since they're being released a year apart. This is something, incidentally, that Jackson's own Lord of the Rings trilogy achieves in adapting a single novel that was split into three volumes at the insistence of Tolkien's publisher, even if the writers have to strain mightily to make it happen (especially in The Two Towers, where as a consequence the seams are most obvious). For The Hobbit, Jackson didn't even try.

The plot, what there is of it: The company of dwarves having finally reached the Lonely Mountain, their 'burglar', hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Martin Freeman), steals the Arkenstone from Smaug the dragon (Benedict Cumberbatch). Angered, Smaug flies off to Lake-town and burns it to the ground, but is slain by Bard the Bowman (Luke Evans) in the process. Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage), suddenly freed from the headache of how to get rid of Smaug, refounds the dwarven kingdom of Erebor and, increasingly overcome by the allure of gold, has his followers fortify the entrance before others stake a claim. As indeed they do: Bard arrives with the people of Lake-town to demand the share of the treasure Thorin promised, to help rebuild the town; he is soon joined by the army of King Thranduil of the wood-elves (Lee Pace), who is incensed at Thorin deceiving and escaping him. Thorin's pig-headed refusal to negotiate is backed up when his cousin Dáin Ironfoot (Billy Connolly) arrives with an army of dwarves. Before the sides come to blows, however, a horde of orcs led by Azog the Defiler (Manu Bennett) shows up and much mayhem ensues.

There's also a subplot involving Gandalf and some characters you may remember from the Rings films fighting the necromancer in Dol Guldur, but that takes up all of five minutes.

The Battle of the Five Armies is pretty to look at, no doubt: the wintry surrounds of the Lonely Mountain are a triumph of landscape photography, set design and cinematography. Set in cold northern wastes the Rings films never touched on, The Battle of the Five Armies serves up new, interesting environs. And there are some genuine thrills there, too: Dáin's dwarven phalanx in action is a sight to see, even if the Warhammer-esque blockiness of the dwarf design, which I've never been a fan of, still spoils the view somewhat.

On the downside there are the terrible CGI-enhanced baddies. The Rings films, for all the criticism rightly levelled at them, were heaven for fans of practical effects. The design of the orcs, using masks, prosthetics and make-up, gave the creatures a gross physicality that lined up with the spittle, body odour and vile dietary habits that defined them as fictional versions of the working-class people of Tolkien's patrician nightmares. CGI allows the creation of wonders that old-school effects have never been able to achieve, but the trade-off is still often a lack of heft and weight.

There is no reality and thus no threat to these orcs, snarl as they might. Compare the magnificant fight between Aragorn and Lurtz in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) to Thorin's endless, mind-numbingly boring battle against Azog in this one, and despair. (A similar scene, in which Legolas leaps along a collapsing walkway like Super Mario, caused peals of laughter to ring around the auditorium.) With the Hobbit films (let's just boldly assume this problem affects the previous two films as well), Jackson has gone full-on Phantom Menace.

The film is hopelessly dragged down is its sheer length, forced by the mercenary decision to turn The Hobbit not into one, nor two, but three feature-length films. Reverse that decision, and this entire film could be wrapped up in the 45 minutes the material merits; the enormous structural problem would disappear; the fact that the nominal protagonist has nothing to do would be much less noticeable. Lengthy, pointless scenes involving cowardly Alfrid (Ryan Gage), in which jokes about such humorous subjects as men wearing women's clothes are expected to provide comic relief, could be cut, as could a bizarre psychedelic sequence involving Thorin among Smaug's gold that shows us Jackson using the freedom granted by a near-total absence of plot to baffling effect.

But the film's length isn't its only problem: indeed some fairly important aspects of the book are passed over in downright indecent haste (the arrival of Beorn and the eagles), while threads are left dangling in other places (we're left to assume, for example, that Dáin and the elves defeated the orc army after its leaders are killed elsewhere, but the film doesn't see the need to spell out the outcome of the titular battle). There's the film's uninspiring visual language too: where Rings had stunning images, even if they were often an homage to greater works, The Battle of the Five Armies offers little to look at, as if Jackson was overcompensating for his tendency to gawk at his sets.

Anyway, I'm glad this new trilogy is over, and sort of pleased Jackson doesn't have the rights to any more of Tolkien's works.

Wednesday, 3 July 2013

Why'd it have to be snakes?

Some things I enjoy now were acquired tastes. Horror, for example, I mostly disliked throughout my formative years. But I've loved globe-trotting adventures since I was little. I grew up reading Verne, Stevenson, May and Haggard, even though I didn't realise the horrid colonial subtext at the time. So when I first watched the Indiana Jones films - late: around the time the retroactively reviled Kingdom of the Crystal Skull came out - I enjoyed them tremendously.

So I was pretty delighted when the local semi-arthouse cinema did a one-off screening of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). The first of the Lucas-Spielberg films involving Harrison Ford's adventurer archaeologist had been the one I enjoyed least (except for that belated fourth film, which nobody seems to count): I knew it was good, but the earlier incarnation of the franchise couldn't quite match the finely honed machine of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). So I watched it again, had an enormous amount of fun and left with a furrowed brow over all the problematic stuff in it.

Set in 1936, the film opens as Dr Henry 'Indiana' Jones (Harrison Ford) is exploring an ancient site somewhere in South America. Improvising his way around wicked traps, Indy manages to snag a golden idol despite the treachery of a local hired hand (Alfred Molina). He promptly finds himself relieved of his prize by his rival, the ruthless French archaeologist Belloq (Paul Freeman), barely escaping with his life. Back in the States, Indy is given a new mission by the secret service. It seems that the Nazis are digging in Egypt, having tasked Belloq with finding the Ark of the Covenant. To reveal its exact location, though, they need the Staff of Ra, which is in the possession of Indy's old patron Abner Ravenwood, last known location...

... Nepal, where after Abner's death his daughter Marion (Karen Allen) keeps the headpiece of the staff. The problem: Marion is none too keen on Indy after he broke her heart ten years previously. Fighting for their lives against goons led by giggling Nazi sadist Major Toht (Ronald Lacey), though, does something to repair the lost trust, and the pair make it to Egypt with the staff. There, they link up with local digger Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) to infiltrate the Nazi excavation, and hopefully locate the Ark before the Führer's men do.

What struck me as a tiresome flaw during a recent viewing of Star Trek Into Darkness is a virtue here: Raiders of the Lost Ark is gloriously propulsive, barely letting up from start to finish. Even exposition tends to be loaded with background action: take the dinner at Sallah's, where Spielberg and Lucas throw poisoned dates into an already fun dialogue scene. After the US-bound table-setting the film does not slow down until the dénouement, although Lawrence Kasdan - he of The Empire Strikes Back - is a smart enough writer that by the time the relentless action scenes finally get a little wearying, he switches to a lower gear so that the film's climax is heavy on tension but light on fisticuffs.

The cast is uniformly great. Harrison's perpetually exasperated adventurer archaeologist is of course iconic, played here perhaps with a little more meanness than in subsequent offerings; Denholm Elliott's Marcus Brody is such a delight that it's no surprise Last Crusade expanded his role. I must admit I have a massive fictional-character crush on Allen's Marion, and I hope my judgment is not too terribly clouded by that, but: what a fantastic character! When introduced, at least: Marion drinking a local under the table, then holding her own in a battle against Toht's henchmen is pretty awesome. Unfortunately, Kasdan's screenplay proceeds to defang her. Being put into dresses, in fact, becomes a plot point, and she's an increasingly distressed damsel relying on Indy for rescue and basic common sense.

That's the real problem with Raiders of the Lost Ark: based on 1930s adventure serials, the film somehow sees fit to just bring in all the racism and misogyny of that period instead of challenging it. Marion's demotion is the least of it, alas. The film's racism is ugly and pervasive. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom takes a lot of flak for racism, and deservedly so; but its predecessor is no better by any real yardstick. Its non-white people, to be sure, are not crazed murdering cultists: they are mostly childlike innocents requiring the kind guidance of the white man. A narrative in which white people are masters and Egyptians mere labourers is never seriously challenged (see the image above). Worse, the ambiguous South Americans are treacherous, lazy and cowardly and, in the case of the indigenous warriors Belloq has allied himself with, primitive and superstitious. It's totally unnecessary and leaves a terrible aftertaste.

Despite that, too, being mostly associated with its immediate successor, Raiders is pretty brutal, featuring multiple unpleasant deaths, mostly bloodless though they may be (and in one infamous scene involving a Nazi bare-knuckle boxer and an aeroplane propeller, it's decidedly not bloodless). There's violence against animals as well, including a whole mess of snakes being doused with petrol and set on fire, and an unfortunate monkey. It's better than an Italian cannibal film inasmuch as it's not real, I suppose, but far from pleasant or called for. Like Tintin in the Congo, Raiders presents the killing of animals is harmless entertainment, and the thought that it might be something else never crosses the film's mind.

If that doesn't sour your appreciation, though, Raiders of the Lost Ark is overflowing with joys. Norman Reynolds's production design is just wonderful: the Ark marries an ancient feel with art-déco chic in just the right way, while the South American temple is a laundry list of wonderfully executed tropes. (Who doesn't love ancient traps?) More than anything, it shows what the people involved were best at: Spielberg, at being the greatest blockbuster director of his generation; Kasdan, at marrying drama and action-comedy; and Lucas, at taking a step back and using his genius for production without directing himself, a lesson he sadly did not heed in later years (see also: Jackson, Peter).

It's such a delightful film that its less savoury aspects are a whole lot easier to overlook than they might be. With the double-whammy of Empire and Raiders, Kasdan clearly had a winning streak in the first half of the eighties (even Return of the Jedi, weighed down by merchandise-friendly teddy bears and material rehashed from Star Wars, is ultimately well-written, devastatingly so in some scenes). Raiders of the Lost Ark is tremendously good fun: populist but not stupid, hilarious without being tasteless, and action-packed without directing that violence at the audience in the manner of twenty-first-century action films.

So I was pretty delighted when the local semi-arthouse cinema did a one-off screening of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). The first of the Lucas-Spielberg films involving Harrison Ford's adventurer archaeologist had been the one I enjoyed least (except for that belated fourth film, which nobody seems to count): I knew it was good, but the earlier incarnation of the franchise couldn't quite match the finely honed machine of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). So I watched it again, had an enormous amount of fun and left with a furrowed brow over all the problematic stuff in it.

Set in 1936, the film opens as Dr Henry 'Indiana' Jones (Harrison Ford) is exploring an ancient site somewhere in South America. Improvising his way around wicked traps, Indy manages to snag a golden idol despite the treachery of a local hired hand (Alfred Molina). He promptly finds himself relieved of his prize by his rival, the ruthless French archaeologist Belloq (Paul Freeman), barely escaping with his life. Back in the States, Indy is given a new mission by the secret service. It seems that the Nazis are digging in Egypt, having tasked Belloq with finding the Ark of the Covenant. To reveal its exact location, though, they need the Staff of Ra, which is in the possession of Indy's old patron Abner Ravenwood, last known location...

... Nepal, where after Abner's death his daughter Marion (Karen Allen) keeps the headpiece of the staff. The problem: Marion is none too keen on Indy after he broke her heart ten years previously. Fighting for their lives against goons led by giggling Nazi sadist Major Toht (Ronald Lacey), though, does something to repair the lost trust, and the pair make it to Egypt with the staff. There, they link up with local digger Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) to infiltrate the Nazi excavation, and hopefully locate the Ark before the Führer's men do.

What struck me as a tiresome flaw during a recent viewing of Star Trek Into Darkness is a virtue here: Raiders of the Lost Ark is gloriously propulsive, barely letting up from start to finish. Even exposition tends to be loaded with background action: take the dinner at Sallah's, where Spielberg and Lucas throw poisoned dates into an already fun dialogue scene. After the US-bound table-setting the film does not slow down until the dénouement, although Lawrence Kasdan - he of The Empire Strikes Back - is a smart enough writer that by the time the relentless action scenes finally get a little wearying, he switches to a lower gear so that the film's climax is heavy on tension but light on fisticuffs.

|

| The film's idea of appropriate race relations. |

The cast is uniformly great. Harrison's perpetually exasperated adventurer archaeologist is of course iconic, played here perhaps with a little more meanness than in subsequent offerings; Denholm Elliott's Marcus Brody is such a delight that it's no surprise Last Crusade expanded his role. I must admit I have a massive fictional-character crush on Allen's Marion, and I hope my judgment is not too terribly clouded by that, but: what a fantastic character! When introduced, at least: Marion drinking a local under the table, then holding her own in a battle against Toht's henchmen is pretty awesome. Unfortunately, Kasdan's screenplay proceeds to defang her. Being put into dresses, in fact, becomes a plot point, and she's an increasingly distressed damsel relying on Indy for rescue and basic common sense.

That's the real problem with Raiders of the Lost Ark: based on 1930s adventure serials, the film somehow sees fit to just bring in all the racism and misogyny of that period instead of challenging it. Marion's demotion is the least of it, alas. The film's racism is ugly and pervasive. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom takes a lot of flak for racism, and deservedly so; but its predecessor is no better by any real yardstick. Its non-white people, to be sure, are not crazed murdering cultists: they are mostly childlike innocents requiring the kind guidance of the white man. A narrative in which white people are masters and Egyptians mere labourers is never seriously challenged (see the image above). Worse, the ambiguous South Americans are treacherous, lazy and cowardly and, in the case of the indigenous warriors Belloq has allied himself with, primitive and superstitious. It's totally unnecessary and leaves a terrible aftertaste.

Despite that, too, being mostly associated with its immediate successor, Raiders is pretty brutal, featuring multiple unpleasant deaths, mostly bloodless though they may be (and in one infamous scene involving a Nazi bare-knuckle boxer and an aeroplane propeller, it's decidedly not bloodless). There's violence against animals as well, including a whole mess of snakes being doused with petrol and set on fire, and an unfortunate monkey. It's better than an Italian cannibal film inasmuch as it's not real, I suppose, but far from pleasant or called for. Like Tintin in the Congo, Raiders presents the killing of animals is harmless entertainment, and the thought that it might be something else never crosses the film's mind.

If that doesn't sour your appreciation, though, Raiders of the Lost Ark is overflowing with joys. Norman Reynolds's production design is just wonderful: the Ark marries an ancient feel with art-déco chic in just the right way, while the South American temple is a laundry list of wonderfully executed tropes. (Who doesn't love ancient traps?) More than anything, it shows what the people involved were best at: Spielberg, at being the greatest blockbuster director of his generation; Kasdan, at marrying drama and action-comedy; and Lucas, at taking a step back and using his genius for production without directing himself, a lesson he sadly did not heed in later years (see also: Jackson, Peter).

It's such a delightful film that its less savoury aspects are a whole lot easier to overlook than they might be. With the double-whammy of Empire and Raiders, Kasdan clearly had a winning streak in the first half of the eighties (even Return of the Jedi, weighed down by merchandise-friendly teddy bears and material rehashed from Star Wars, is ultimately well-written, devastatingly so in some scenes). Raiders of the Lost Ark is tremendously good fun: populist but not stupid, hilarious without being tasteless, and action-packed without directing that violence at the audience in the manner of twenty-first-century action films.

Labels:

action,

adventure,

archaeology,

blockbuster,

mysterious orient,

pastiche,

race

Friday, 4 January 2013

Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in

Sixteen years passed between the universal acclaim of The Godfather Part II and its belated epilogue. In the meantime, Francis Ford Coppola struck gold again with Apocalypse Now, but at the price of an infamously gruelling shoot. In the eighties, the director suffered a long string of flops and misfires, bottoming out with Tucker: The Man and His Dream. Exhausted and close to bankruptcy, Coppola finally accepted Paramount Pictures' long-standing offer to direct a third film in the series that had put him on the map.

The circumstances surrounding that film, finally released in December 1990, were a recipe for disaster. The Godfather Part III was a blatant cash grab. It was missing Robert Duvall, who declined to return after being offered too small a fraction of Al Pacino's salary. Most ominously, Coppola wanted the film to be a smaller-scale epilogue titled The Death of Michael Corleone, but the studio insisted on the Part III title.

The film's reception was far less glowing than its predecessors', but it was usually considered flawed, tacked-on and inessential rather than a true disaster: the first film in the series to include real, substantial misjudgments, but not bad per se. The temptation is to declare that if only it wasn't a part of the Godfather series and derived unearned canonisation from them, we should hail it as a pretty good gangster picture. But that doesn't really stand up to scrutiny. Like Michael Corleone himself Part III is obsessed with the events of the previous films and derives all its substance from them. It's a mood piece that meditates on the first two films, exploring how they resonate two decades down the line and whether there is any escape from the cycle of violence. I'm partial to that.

It certainly doesn't help, though, that The Godfather Part III opens with its worst scene, and therefore the weakest scene in the whole franchise. In 1979 Michael (Al Pacino, barely recognisable), pushing sixty and still at the head of the Corleone family, receives an award from the Catholic Church in return for a donation of a hundred million dollars for the needy of Sicily. His ex-wife Kay (Diane Keaton) wants him to allow his son Anthony (Franc D'Ambrosio) to quit his law degree and become a professional singer, but Michael is reluctant. Meanwhile, he has to settle a dispute between crime lord Joey Zasa (Joe Mantegna) and Vincent Mancini (Andy García), a choleric low-level mobster and illegitimate son of Santino Corleone.

It's a clusterfrak of poor choices, beginning with the copious use of footage from the first two films. Generally, the things wrong with this scene will continue to bog down the film, but nowhere else are they present in such concentrated form. There's the infodumping introduction of new characters (George Hamilton as family lawyer B.J. Harrison, John Savage as Andrew Hagen, Eli Wallach as affable ageing gangster Don Altobello), the pointless cameos from Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) to Enzo the baker (Gabriele Torrei) - who actually refers to himself as 'Enzo the baker', for goodness' sake - , and the awful acting and dialogue: the worst in the whole film, in fact, from Keaton's worst work as Kay to a gut-churning 'flirting' scene between Vincent and Mary Corleone (Sofia Coppola).

The film picks up in a tense, profane confrontation between Vincent and Zasa that ends with a savaged ear instead of the peace Michael demands. From there, it gets better: Vincent, attacked in his flat by thugs who threaten his girlfriend Grace Hamilton (Bridget Fonda) and backed by Michael's sister Connie (Talia Shire), champs at the bit to be allowed to strike back at Joey Zasa. At a meeting of the Commission in Atlantic City, Michael pays out his partners' shares in the casino business and dissolves his relationships between them but Joey Zasa, who receives nothing, leaves in anger. Shortly after, the meeting is attacked and most senior gangsters machine-gunned. Michael, who survives uninjured, suffers a diabetic stroke from stress. While he's recovering, Vincent assassinates Joey Zasa with the endorsement of Connie and Al Neri (Richard Bright).

In the film's third act the family relocates to Sicily, where Anthony is due to give his operatic debut in a performance of Cavalleria rusticana. Michael, eager to invest in legitimate enterprises, sees his efforts to control the board of a European real estate company blocked by a shadowy cabal of gangsters, bankers and senior churchmen, and feels forced to order one last round of blood-letting that he no longer has the strength for. He offers Vincent leadership of the family, on condition that the latter end his romance with Mary. But the enemy behind all the machinations against him has ordered a Sicilian assassin (Mario Donatone) to go to the opera and take Michael out once and for all.

At its heart The Godfather Part III is about redemption. Michael Corleone makes one last attempt to make the transition from crime to legitimate business and atone for ordering his brother's death, and he fails. The theme of being unable to shake off the sins of the past no matter how hard one tries explains and, I at least would argue, justifies the film's obsession with its predecessors, its modest ambition to be no more than an epilogue. It also accounts for the sheer amount of religious themes and Catholic iconography strewn all over the film: religion played a part in previous installments, but it is here, between rosaries, Madonnas and important scenes set in the Vatican, that Catholicism is really foregrounded.

In the film's signature scene - in which, unfortunately, we can see the actors' breath, making it tremendously obvious it was filmed somewhere rather colder than southern Italy in the summer - Michael visits Cardinal Lamberto (Raf Vallone) because he needs his assistance against Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly). Overcome by the compassion of a man he later calls 'a true priest', Michael tearfully confesses his sins, but realises he will not repent. 'Your sins are terrible, and it is just that you suffer,' Lamberto says: 'Your life could be redeemed, but I know that you don't believe that. You will not change.' And then, with an infinite sadness, he does his job: 'Ego te absolvo in nomine Patris...'

Michael tries to atone for the sins of his past, but he also wants to ensure a future for his family free of that evil. He struggles with the unconditional love Anthony and Mary display towards him, and tries to repair his relationship with his ex-wife, who loves and dreads him. The problem is that all this material, much of which is the heart of the film, does not work at all. Keaton has the worst dialogue in the film - again, one might say after Part II. Her job has always been to state the films' message in no uncertain terms, at the expense of a character that has sounded increasingly self-righteous and whiny. Saddled with the sort of material she's served here, Keaton gives her worst performance in the franchise.

The other infamous piece of acting is of course Sofia Coppola, cast by her father after Winona Ryder dropped out at the last minute. Coppola, unfortunately, is quite as awful as her detractors say. The film pretty much dies every time she's onscreen, which spells trouble since the climax hinges on her relationship with Pacino. The problem, though, isn't merely nepotism - the Godfather series had always provided gainful employment for the whole Coppola family, not generally to the films' detriment. Sofia Coppola is simply saddled with having to portray the weakest character in the weakest script of the series. Ryder would almost certainly have been better, but I cannot imagine a good performance of this character.

Two facts negate the obvious assumption that the Puzo-Coppola team simply cannot write women. Firstly, D'Ambrosio's Anthony is also a poor character. Secondly, there's Talia Shire, the director's sister and living refutation of the theory that the series' problems are caused by rampant nepotism. Shire had always given strong performances, but in Part III she moves to the centre of the cast, and Connie becomes magnificent as a result: passionate about the family, she has gained an austere ruthlessness that leads her to back the brutal Vincent. The script also makes her Don Altobello's goddaughter, which lends intense poignancy to the scene in which she gives him a box of cannoli for his birthday.* ('Sleep, godfather.')

García is very good too, with the exception of his leaden romance scenes with Sofia Coppola. A murderous thug and little else, his Vincent Mancini is a crucial element in the process of self-demythologisation that began with The Godfather Part II. He's difficult to like and admire, but tremendously easy to fear. Similarly, the shady Don Lucchesi (Enzo Robutti) doesn't look like a film character: he resembles the 'important' people my overly status-conscious bourgeois grandparents used to invite to family functions. He's more accountant than glamorous gangster, but no less pitiless and deadly for that.

The film's direction is a tick less good than its predecessors' and Carmine Coppola's score makes me miss Nino Rota, who was unable to return on account of being dead. But as pure spectacle The Godfather Part III still doesn't disappoint. For starters, the production design is absolutely gorgeous. Art director Alex Tavoularis, joining his brother and series veteran Dean Tavoularis, leaves the somewhat realistic look of Part II far behind and goes for Baroque spectacle: red curtains, gold, daggers, and religious imagery. That pays off in the climactic opera scene, an aural and visual feast that is not the series' most effective sequence but certainly its most spectacular. It almost manages to make you forget a clumsy dénouement marred by abysmal old-age make-up.

The fact of the matter is that I kind of love The Godfather Part III. Yes, it has some fairly horrendous flaws, unlike its near-perfect brethren. And no-one could accuse it of being essential: without it, the saga of Michael Corleone would be no less complete. But beside the spectacle, the film is marked by a deep human yearning for peace, an end to a seemingly neverending cycle of violence. It isn't optimistic in that sense, but it doesn't need to be: the hope for peace itself matters. As long as we have that (as Vincent and Connie do not), all is not lost.

*The last time I watched The Godfather Part III with friends who hadn't seen it before, I made and brought cannoli. I recommend doing that.

In this series: The Godfather (1972) | The Godfather Part II (1974) | The Godfather Part III (1990)

The circumstances surrounding that film, finally released in December 1990, were a recipe for disaster. The Godfather Part III was a blatant cash grab. It was missing Robert Duvall, who declined to return after being offered too small a fraction of Al Pacino's salary. Most ominously, Coppola wanted the film to be a smaller-scale epilogue titled The Death of Michael Corleone, but the studio insisted on the Part III title.

The film's reception was far less glowing than its predecessors', but it was usually considered flawed, tacked-on and inessential rather than a true disaster: the first film in the series to include real, substantial misjudgments, but not bad per se. The temptation is to declare that if only it wasn't a part of the Godfather series and derived unearned canonisation from them, we should hail it as a pretty good gangster picture. But that doesn't really stand up to scrutiny. Like Michael Corleone himself Part III is obsessed with the events of the previous films and derives all its substance from them. It's a mood piece that meditates on the first two films, exploring how they resonate two decades down the line and whether there is any escape from the cycle of violence. I'm partial to that.

It certainly doesn't help, though, that The Godfather Part III opens with its worst scene, and therefore the weakest scene in the whole franchise. In 1979 Michael (Al Pacino, barely recognisable), pushing sixty and still at the head of the Corleone family, receives an award from the Catholic Church in return for a donation of a hundred million dollars for the needy of Sicily. His ex-wife Kay (Diane Keaton) wants him to allow his son Anthony (Franc D'Ambrosio) to quit his law degree and become a professional singer, but Michael is reluctant. Meanwhile, he has to settle a dispute between crime lord Joey Zasa (Joe Mantegna) and Vincent Mancini (Andy García), a choleric low-level mobster and illegitimate son of Santino Corleone.

It's a clusterfrak of poor choices, beginning with the copious use of footage from the first two films. Generally, the things wrong with this scene will continue to bog down the film, but nowhere else are they present in such concentrated form. There's the infodumping introduction of new characters (George Hamilton as family lawyer B.J. Harrison, John Savage as Andrew Hagen, Eli Wallach as affable ageing gangster Don Altobello), the pointless cameos from Johnny Fontane (Al Martino) to Enzo the baker (Gabriele Torrei) - who actually refers to himself as 'Enzo the baker', for goodness' sake - , and the awful acting and dialogue: the worst in the whole film, in fact, from Keaton's worst work as Kay to a gut-churning 'flirting' scene between Vincent and Mary Corleone (Sofia Coppola).

The film picks up in a tense, profane confrontation between Vincent and Zasa that ends with a savaged ear instead of the peace Michael demands. From there, it gets better: Vincent, attacked in his flat by thugs who threaten his girlfriend Grace Hamilton (Bridget Fonda) and backed by Michael's sister Connie (Talia Shire), champs at the bit to be allowed to strike back at Joey Zasa. At a meeting of the Commission in Atlantic City, Michael pays out his partners' shares in the casino business and dissolves his relationships between them but Joey Zasa, who receives nothing, leaves in anger. Shortly after, the meeting is attacked and most senior gangsters machine-gunned. Michael, who survives uninjured, suffers a diabetic stroke from stress. While he's recovering, Vincent assassinates Joey Zasa with the endorsement of Connie and Al Neri (Richard Bright).

In the film's third act the family relocates to Sicily, where Anthony is due to give his operatic debut in a performance of Cavalleria rusticana. Michael, eager to invest in legitimate enterprises, sees his efforts to control the board of a European real estate company blocked by a shadowy cabal of gangsters, bankers and senior churchmen, and feels forced to order one last round of blood-letting that he no longer has the strength for. He offers Vincent leadership of the family, on condition that the latter end his romance with Mary. But the enemy behind all the machinations against him has ordered a Sicilian assassin (Mario Donatone) to go to the opera and take Michael out once and for all.

At its heart The Godfather Part III is about redemption. Michael Corleone makes one last attempt to make the transition from crime to legitimate business and atone for ordering his brother's death, and he fails. The theme of being unable to shake off the sins of the past no matter how hard one tries explains and, I at least would argue, justifies the film's obsession with its predecessors, its modest ambition to be no more than an epilogue. It also accounts for the sheer amount of religious themes and Catholic iconography strewn all over the film: religion played a part in previous installments, but it is here, between rosaries, Madonnas and important scenes set in the Vatican, that Catholicism is really foregrounded.

In the film's signature scene - in which, unfortunately, we can see the actors' breath, making it tremendously obvious it was filmed somewhere rather colder than southern Italy in the summer - Michael visits Cardinal Lamberto (Raf Vallone) because he needs his assistance against Archbishop Gilday (Donal Donnelly). Overcome by the compassion of a man he later calls 'a true priest', Michael tearfully confesses his sins, but realises he will not repent. 'Your sins are terrible, and it is just that you suffer,' Lamberto says: 'Your life could be redeemed, but I know that you don't believe that. You will not change.' And then, with an infinite sadness, he does his job: 'Ego te absolvo in nomine Patris...'

Michael tries to atone for the sins of his past, but he also wants to ensure a future for his family free of that evil. He struggles with the unconditional love Anthony and Mary display towards him, and tries to repair his relationship with his ex-wife, who loves and dreads him. The problem is that all this material, much of which is the heart of the film, does not work at all. Keaton has the worst dialogue in the film - again, one might say after Part II. Her job has always been to state the films' message in no uncertain terms, at the expense of a character that has sounded increasingly self-righteous and whiny. Saddled with the sort of material she's served here, Keaton gives her worst performance in the franchise.

The other infamous piece of acting is of course Sofia Coppola, cast by her father after Winona Ryder dropped out at the last minute. Coppola, unfortunately, is quite as awful as her detractors say. The film pretty much dies every time she's onscreen, which spells trouble since the climax hinges on her relationship with Pacino. The problem, though, isn't merely nepotism - the Godfather series had always provided gainful employment for the whole Coppola family, not generally to the films' detriment. Sofia Coppola is simply saddled with having to portray the weakest character in the weakest script of the series. Ryder would almost certainly have been better, but I cannot imagine a good performance of this character.

Two facts negate the obvious assumption that the Puzo-Coppola team simply cannot write women. Firstly, D'Ambrosio's Anthony is also a poor character. Secondly, there's Talia Shire, the director's sister and living refutation of the theory that the series' problems are caused by rampant nepotism. Shire had always given strong performances, but in Part III she moves to the centre of the cast, and Connie becomes magnificent as a result: passionate about the family, she has gained an austere ruthlessness that leads her to back the brutal Vincent. The script also makes her Don Altobello's goddaughter, which lends intense poignancy to the scene in which she gives him a box of cannoli for his birthday.* ('Sleep, godfather.')

García is very good too, with the exception of his leaden romance scenes with Sofia Coppola. A murderous thug and little else, his Vincent Mancini is a crucial element in the process of self-demythologisation that began with The Godfather Part II. He's difficult to like and admire, but tremendously easy to fear. Similarly, the shady Don Lucchesi (Enzo Robutti) doesn't look like a film character: he resembles the 'important' people my overly status-conscious bourgeois grandparents used to invite to family functions. He's more accountant than glamorous gangster, but no less pitiless and deadly for that.

The film's direction is a tick less good than its predecessors' and Carmine Coppola's score makes me miss Nino Rota, who was unable to return on account of being dead. But as pure spectacle The Godfather Part III still doesn't disappoint. For starters, the production design is absolutely gorgeous. Art director Alex Tavoularis, joining his brother and series veteran Dean Tavoularis, leaves the somewhat realistic look of Part II far behind and goes for Baroque spectacle: red curtains, gold, daggers, and religious imagery. That pays off in the climactic opera scene, an aural and visual feast that is not the series' most effective sequence but certainly its most spectacular. It almost manages to make you forget a clumsy dénouement marred by abysmal old-age make-up.

The fact of the matter is that I kind of love The Godfather Part III. Yes, it has some fairly horrendous flaws, unlike its near-perfect brethren. And no-one could accuse it of being essential: without it, the saga of Michael Corleone would be no less complete. But beside the spectacle, the film is marked by a deep human yearning for peace, an end to a seemingly neverending cycle of violence. It isn't optimistic in that sense, but it doesn't need to be: the hope for peace itself matters. As long as we have that (as Vincent and Connie do not), all is not lost.

*The last time I watched The Godfather Part III with friends who hadn't seen it before, I made and brought cannoli. I recommend doing that.

In this series: The Godfather (1972) | The Godfather Part II (1974) | The Godfather Part III (1990)

Sunday, 30 December 2012

One by one, our old friends are gone

Despite a three-star Roger Ebert review that has angered fanboys for four decades, The Godfather Part II is, if anything, even more critically acclaimed than its predecessor. But among audiences, Coppola's sequel has never been able to catch up with the then highest grossing film of all time. Virtually all the franchise's famous lines and characters are from the first installment. A large segment of the moviegoing public, convinced it's all about Vito Corleone, is unable to strike up a connection to the Marlon Brando-less sequels.

But that's hardly the result of the first-year university student's favourite bugbear, the stupidity of the common man. It's all in the material. The Godfather Part II is brilliant, but it's much harder to like than its predecessor. Detached and critical where the first film is engrossing, Part II functions as a deconstruction of The Godfather's oft-criticised glamorisation of the Cosa Nostra. In Al Pacino's cold, calculating Michael Corleone it has a protagonist only in the technical sense: it's virtually impossible to root for him.

In 1901, Antonio Andolini is murdered by the Mafia don of Corleone, Sicily. His funeral procession is disturbed by shotgun blasts that signal the murder of Andolini's oldest son, Paolo, who had gone to seek revenge. Heartbroken, Paolo's mother (Maria Carta) goes to see Don Ciccio (Giuseppe Sillato) to plead for the life of her only remaining son, nine-year-old Vito (Oreste Baldini), but the don refuses. Vito's mother is killed, but Vito manages to flee Sicily and make it to the United States. There, an immigration official mistakenly writes down his name as Vito Corleone.

At Lake Tahoe in 1958, the Corleone family and their many friends celebrate the first communion of Don Michael's son Anthony Corleone. There's trouble in the family, though. Michael's sister Connie (Talia Shire), still wounded by the murder of her husband in Part I, is neglecting her children and cavorting with a man the family disapproves of. Fredo (John Cazale) is unhappy in his marriage, Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall) is increasingly shut out by Michael, Nevadan senator Geary (G.D. Spradlin) is causing trouble for the casino business, and New York caporegime Frank Pentangeli (Michael V. Gazzo) is dissatisfied with Michael's refusal to let him strike at his rivals. When Michael and his family barely survive a hit that same night, it's hardly a surprise.

The rest of the film is about Michael's attempt to uncover and defeat the conspiracy against him. Somehow involved is the reptilian Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg). An elderly Jewish gangster living in Miami, Roth has organised a coalition of American business interests to carve up the Cuban economy with the full cooperation of Fulgencio Batista's government. While publicly declaring his intention to turn over his business to Michael after his death, Roth is angered by Michael's reticence in providing an agreed cash investment. After the little matter of the Cuban Revolution foils Roth's plans, the relationship of the two men turns openly hostile.

Meanwhile, the film flashes back to a younger Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) struggling to make a living in Manhattan's Little Italy in the 1910s and 1920s. After acquiring a rug that really ties the room together as a thanks from petty criminal Clemenza (Bruno Kirby), Vito begins to supplement his income with theft and burglary. Inevitably this puts him on a collision course with Fanucci (Gastone Moschin), the local Black Hand don who extorts protection money from businesses. After dispatching Fanucci, Vito expands his operations and sets up an olive oil import business as a legitimate front.