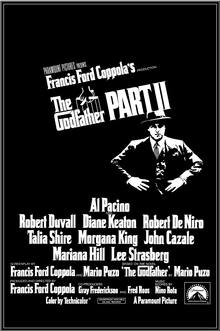

But that's hardly the result of the first-year university student's favourite bugbear, the stupidity of the common man. It's all in the material. The Godfather Part II is brilliant, but it's much harder to like than its predecessor. Detached and critical where the first film is engrossing, Part II functions as a deconstruction of The Godfather's oft-criticised glamorisation of the Cosa Nostra. In Al Pacino's cold, calculating Michael Corleone it has a protagonist only in the technical sense: it's virtually impossible to root for him.

In 1901, Antonio Andolini is murdered by the Mafia don of Corleone, Sicily. His funeral procession is disturbed by shotgun blasts that signal the murder of Andolini's oldest son, Paolo, who had gone to seek revenge. Heartbroken, Paolo's mother (Maria Carta) goes to see Don Ciccio (Giuseppe Sillato) to plead for the life of her only remaining son, nine-year-old Vito (Oreste Baldini), but the don refuses. Vito's mother is killed, but Vito manages to flee Sicily and make it to the United States. There, an immigration official mistakenly writes down his name as Vito Corleone.

At Lake Tahoe in 1958, the Corleone family and their many friends celebrate the first communion of Don Michael's son Anthony Corleone. There's trouble in the family, though. Michael's sister Connie (Talia Shire), still wounded by the murder of her husband in Part I, is neglecting her children and cavorting with a man the family disapproves of. Fredo (John Cazale) is unhappy in his marriage, Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall) is increasingly shut out by Michael, Nevadan senator Geary (G.D. Spradlin) is causing trouble for the casino business, and New York caporegime Frank Pentangeli (Michael V. Gazzo) is dissatisfied with Michael's refusal to let him strike at his rivals. When Michael and his family barely survive a hit that same night, it's hardly a surprise.

The rest of the film is about Michael's attempt to uncover and defeat the conspiracy against him. Somehow involved is the reptilian Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg). An elderly Jewish gangster living in Miami, Roth has organised a coalition of American business interests to carve up the Cuban economy with the full cooperation of Fulgencio Batista's government. While publicly declaring his intention to turn over his business to Michael after his death, Roth is angered by Michael's reticence in providing an agreed cash investment. After the little matter of the Cuban Revolution foils Roth's plans, the relationship of the two men turns openly hostile.

|

| Vito's mother mourns her oldest son while Vito watches from background right. |

Meanwhile, the film flashes back to a younger Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) struggling to make a living in Manhattan's Little Italy in the 1910s and 1920s. After acquiring a rug that really ties the room together as a thanks from petty criminal Clemenza (Bruno Kirby), Vito begins to supplement his income with theft and burglary. Inevitably this puts him on a collision course with Fanucci (Gastone Moschin), the local Black Hand don who extorts protection money from businesses. After dispatching Fanucci, Vito expands his operations and sets up an olive oil import business as a legitimate front.

The Godfather Part II doesn't mimic its predecessor's expert use of the three-act structure, opting for a more level narrative and the back-and-forth between present and period scenes instead. But many of the beats fall into the same place and fulfil equivalent functions, and they're all much nastier. The opening celebration is hollow and conflict-laden. Where Woltz was turned into a vassal of the Corleones after finding a horse head in his bed, Geary wakes up in a brothel next to a dead woman. ('This girl has no family. Nobody knows that she worked here. It'll be as though she never existed,' Tom Hagen assures him.) At the end of the film, those paying for their defiance of Michael Corleone with their lives are not real threats like Don Barzini and his allies, but defeated and isolated people on the run. ('I don't feel I have to wipe everybody out,' Michael explains. 'Just my enemies, that's all.')

|

| 'Don't worry about anything, Frankie Five-Angels.' |

In its structure, then, the film undermines the sympathies Part I encouraged in the audience. The Godfather Part II thus becomes a critique of its own predecessor, indeed a self-critique by Francis Ford Coppola, who was bothered by accusations of glorifying organised crime with his sympathetic portrayal of the Corleone family. In a series of committee hearings, Michael is questioned by senators (portrayed by the likes of Roger Corman and Richard Matheson). It is, I believe, the first time in the series terms like 'Mafia' and 'Cosa Nostra' are spoken without the halo of 'honour', 'respect' and the rest of the claptrap that these films' criminals invoke to convince themselves they're more than gun thugs who got rich.

If it's a far more searing indictment of organised crime, though, The Godfather Part II also blurs the line between the strong-arm tactics of legal and illegal enterprise more thoroughly than its predecessor. 'This kind of government knows how to help business, to encourage it,' Roth says in praise of the Batista dictatorship.'We have now what we have always needed: real partnership with a government.' The film's most overt satire comes in a boardroom meeting that brings together the Cuban president, gangsters, representatives from American corporations, and a solid gold telephone. Crime and law enforcement are more thoroughly entwined, too: where Sonny Corleone spat at the FBI, in the sequel policemen are brought drinks by Michael Corleone's waiters.

The film's greater maturity is seen in markedly more subdued acting, with the exception of Gazzo's histrionic Pentangeli. De Niro, hardly recognisable to those used his last two decades of self-parody, is a revelation. Pacino's Michael continues becoming colder, ever less capable of ordinary human affection. 'All our people are businessmen', he knows: 'Their loyalty is based on that.' Yet he continues turning away people who care about him - Tom, Kay, Connie - in favour of those businessmen. In The Godfather Part II, his evolution from idealistic war hero to unscrupulous gangster is completed in a sequence that exceeds the heights reached by the already terrific ending of The Godfather. It's a sad and lonely place, and it's where the character's arc finds its logical conclusion. Accountants thought otherwise, though...

In this series: The Godfather (1972) | The Godfather Part II (1974) | The Godfather Part III (1990)

Nice and insightful drawing of the thematic contrast between I and II, thanks for this. Particularly love the "rug that really tied the room together"!

ReplyDeleteThat was originally just a throwaway line, but now I'm imagining Vito protesting being accosted by Don Fanucci with a heartfelt "Hey, careful, man, there's a beverage here!"

Delete(Or: "Signor Fanucci draws a lot of water in this town. You don't draw shit, Corleone.")

There's definitely mashup potential.